“But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary.” (James Madison, The Federalist No. 51; February 6, 1788)

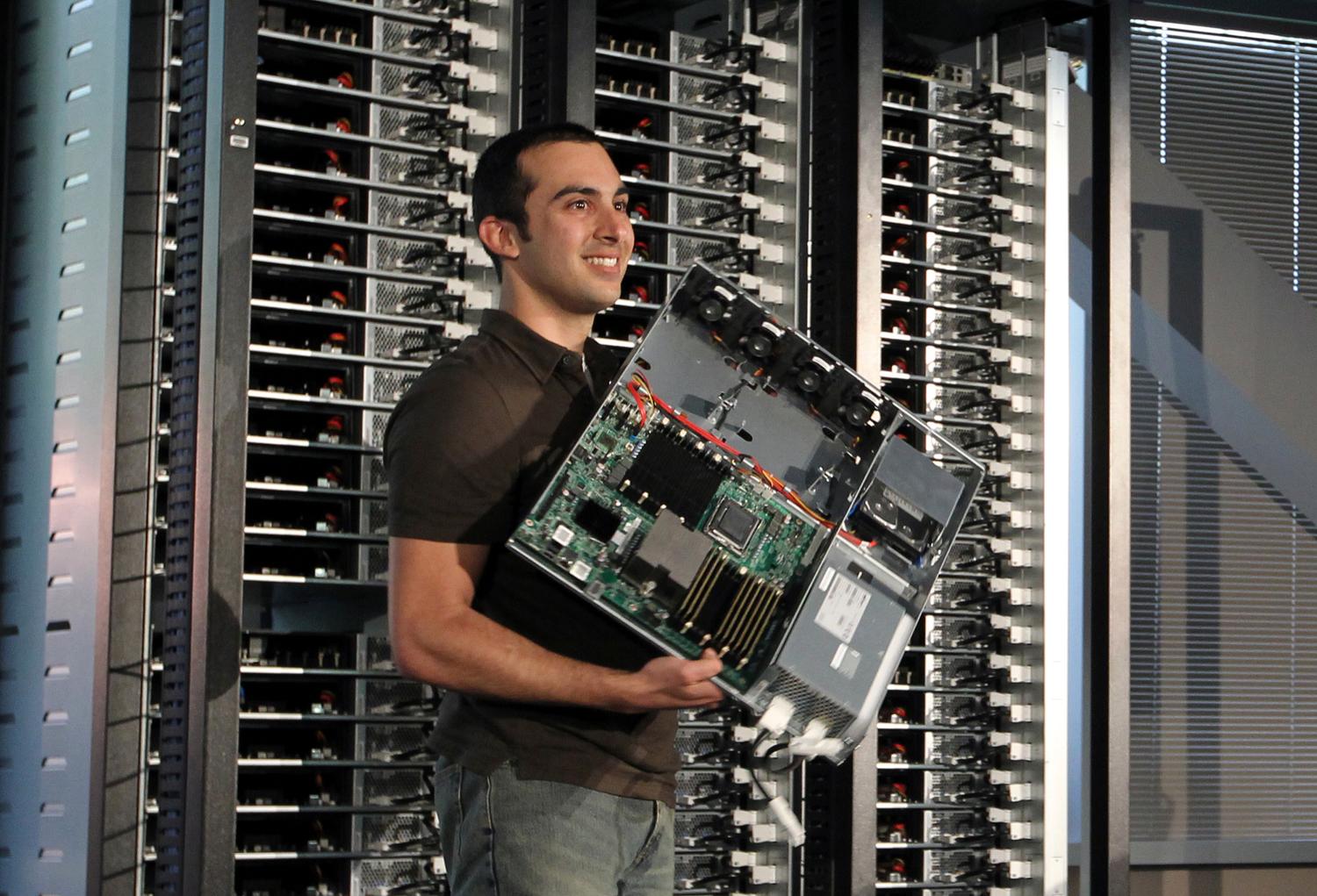

Technology is rapidly changing our world. Traditionally, a nation’s physical borders could mark the beginning of their sovereign space, but in the early to mid-20th century airplanes challenged this notion. Later on, space-based satellites began flying in space above all nations. By the early 21st century, smartphone technologies costing $100 or so gave individuals computational capabilities that dwarfed the multi-million dollar computers operated by large nation-states just three decades earlier.

In this period of exponential change, all of us across the public sector must work together, enabling more inclusive work across government workers, citizen-led contributions, and public-private partnerships. Institutions must empower positive change agents on the inside of public service to pioneer new ways of delivering superior results. Institutions must also open their data for greater public interaction, citizen-led remixing, and discussions.

All together, these actions will transform public service to truly be “We the (mobile, data-enabled, collaborative) People” working to improve our world. These actions all begin creating creative spaces that allow public service professionals the opportunities to experiment and explore new ways of delivering superior results to the public.

21st Century Reality #1:

Public service must include workspaces for those who want to experiment and explore new ways of delivering results.

The world we face now is dramatically different then the world of 50, 100, or 200 years ago. More technological change is expected to occur in the next five years than the last 15 years combined. Advances in technology have blurred what traditionally was considered government, and consequentially we must experiment and explore new ways of delivering results.

21st Century Reality #2: Public service agencies need, within reason, to be allowed to have things fail, and be allowed to take risks.

The words “expertise” and “experiments” have the same etymological root, which is “ex peria,” meaning “out of danger.” Whereas the motto in Silicon Valley and other innovation hubs around the world might be “fail fast and fail often,” such a model is not going to work for public service, where certain endeavors absolutely must succeed and cannot waste taxpayer funds.

The only way public sector technologists will gain the expertise needed to respond to and take advantage of the digital disruptions occurring globally will be to do “dangerous experiments” as positive change agents akin to what entrepreneurs in Silicon Valley also do.

There is no textbook for how to best do public service in an exponential era of rapid technological and social change. We need public service leaders willing to empower and encourage public service change agents to explore non-traditional problem-solving approaches, while also maintaining the intentional system of checks and balances between the public and private sectors.

21st Century Reality #3: Public service cannot be done solely by government professionals in a top-down fashion.

With the communication capabilities provided by smartphones, social media, and freely available apps, individual members of the public can voluntarily access, analyze, remix, and choose to contribute data and insights to better inform public service. Recognizing this shift from top-down to bottom-up activities represents the first step to the resiliency of our legacy institutions.

Public service needs to be allowed to have things fail and to take risks within reason. Certain endeavors absolutely must succeed and cannot waste taxpayer funds, though public service must adapt to our exponentially changing world. Thus public service must include workspaces for those who want to experiment and explore new ways of delivering results.

Shifting from a top-down approach to public service to a bottom-up one begins with championing positive change agents–entrepreneurial actors on the inside of an organization with autonomy to identify and propose solutions to problems, measurable progress on their self-led efforts, and meaningful missions.

Putting a cultural shift into practice

Senior executives need to shift from managing those who report to them to championing and creating spaces for creativity within their organizations. Within any organization, change agents should be able to approach an executive, pitch new ideas, bring data to support these ideas, and if a venture is approved move forward with speed to transform public service away from our legacy approaches.

In turn, senior executives must shift their roles to recruiting, encouraging, and rewarding creative problem solvers, who were empowered to take action to resolve longstanding issues and would be held accountable to address issues within their domain with the backing and willingness of the executive to “take flak” if friction were to occur. This includes executives operating as internal venture capitalists on new, experimental ideas to transform how their organization delivers services faster, more effectively, and with better outcomes for the public.

Such a cultural shift can include simply letting employees know that a safe space exists where they can bring forward good ideas relative to technology, process change, and improving the delivery of an organization’s different missions.

Public service should also experiment with hiring public service professionals tied not to a specific organization, but rather serving as cross-domain professionals able to work on projects as needed across agencies. These cross-domain individuals would need to recognize potential change agent opportunities and also be skilled at building coalitions, short- and long-term strategies, and action plans to ensure public service keeps a pace with our exponential era ahead.

Such a bottom-up, cross-domain workforce could work on multiple projects at the same time or priority projects that span the domains of multiple agencies. Agencies could have funds to obtain the services of such change agents. The cross-domain workforce also could include public service “reservists” similar to the reserve with National Guard, with members of the public choosing to offer part-time assistance in a reserve capacity on important issues, while also working full-time jobs in the private sector.

Transformational partnerships with the public

In addition to inverting public service from top-down approaches to championing bottom-up change agents, public service needs to explore new ways of collaborating with the public and private sector.

Not all the work that public service historically had to do – when communication and computational abilities were once limited – now has to be done by government professionals: some of this work can be done by the public if they want to volunteer.

Back in 2013, the Federal Communications Commission released an open source Speed Test app that enabled the public to download, test their connection speed at a given place and time, and share their result anonymously with the FCC. This experiment produced “crowdsourced” maps of connection speed by provider across the nation, and for a while it was the fourth most downloaded app on the iOS store right behind Google Chrome. By making the code open source, both interested individuals and public interest groups could confirm that the application did not collect an individual’s IP address nor their location beyond a general five mile radius, and thus had privacy “baked-in” by design.

The work of public service also can be done by public-private partnerships acting beyond their own corporate interests to benefit the nation and local communities. Historically the U.S. has lagged other nations, like Singapore or the U.K., in exploring new innovative forms of public-private partnerships. This could change by examining the pressing issues of the day and considering how the private sector might solve challenging issues, or complement the efforts of government professionals. This could include rotations of both government and private sector professionals as part of public-private partnerships to do public service that now might be done more collaboratively, effectively, and innovatively using alternative forms of organizational design and delivery.

If public service returns to first principles – namely, what “We the People” choose to do together – new forms of organizing, collaborating, incentivizing, and delivering results will emerge. Our exponential era requires such transformational partnerships for the future ahead.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Idea to retire: Leaders can’t take risks or experiment

January 29, 2016