Introductory note: The proposal for reforming the State Department presented here has been endorsed and further elaborated by the U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century, co-chaired by former Senators Warren Rudman and Gary Hart. The Commission’s Final Report, Roadmap for National Security: Imperative for Change, was publicly released on January 31, 2001.

As the nation’s 65th secretary of State, Gen. Colin Powell has taken the helm of a State Department in decline. Today, State leads American foreign policy in name only. Presidents regularly disregard its advice or even fail to solicit it. On a wide range of issues, other executive departments play a large, growing, and independent foreign policy role. Special presidential envoys, representatives, and issue managers have proliferated, bypassing regular State Department channels. Funding for the department has been cut 50 percent in real terms since 1985. State’s fading influence is in turn fueling the exodus of many of its most talented young people, who are leaving for careers in the private sector in which pay is plentiful, promotions promising, and power prevalent.

For understandable reasons, then, State’s employees greeted Powell’s selection with jubilation. He is a proven leader who has pledged to use his immense personal stature to help restore the department’s standing. He certainly lost no time in making State’s case for more resources. He spoke eloquently in his nomination hearings of the need to repair America’s “dilapidated embassies.” Just as important, Powell immediately began using his personal touch to rebuild departmental morale. He drew loud applause from the throng of State Department employees who welcomed him on his first full day of work by calling them “colleagues” and “experts.”

Secretary Powell no doubt will make a difference. Good leadership does. But more resources and punchy pep rallies alone will not cure State’s ills. Achieving that mammoth task also requires an organizational structure that works. That kind of organization is sorely lacking. Years of well-intentioned but poorly thought through reforms have crippled the State Department. Authority is broadly dispersed, accountability is hard to find, and decisions are far too long in coming.

Fixing State’s organizational weakness should be one of Secretary Powell’s highest priorities. An effective American foreign policy depends on a strong State Department. So does Powell’s own success. Even a leader with his immense talents will be undone if the organization cannot do what is asked of it. As Dwight Eisenhower, himself no stranger to the importance of leadership, once observed, bad organization “can scarcely fail to lead to inefficiency and can easily lead to disaster.”

State Department employees should welcome efforts to reform the department. Powell will not be secretary forever, and his successors are unlikely to match his leadership skills or political stature. The standing that State regains under his leadership could quickly fade. So it is critical that Powell leave behind an organization stronger than the one he inherited.

But organizational revitalization needs to be done right. Repeating the mistakes of the past and further dispersing authority will make matters worse. Instead, reform should harness the unique talents and expertise of the Foreign Service, give them authority to go along with responsibility, and integrate regional and functional issues into a coherent whole. The United States Commission on National Security/21st Century (the Hart-Rudman Commission) has proposed just such a revitalization in its final report, Roadmap for Leadership: Imperative for Change.

The Causes of Decline

What accounts for State’s weakness? Poor leadership is one culprit. James Baker had close ties to the president, but he chose to ignore rather than lead the department, relying instead on a few trusted and loyal aides. Warren Christopher and Madeleine Albright had neither a clear strategic vision for American foreign policy nor a plan for getting the most out of the department’s many talented people. Even more important, neither had the unquestioned confidence of the president. As a result, their advice was often disregarded and their lack of clout painfully apparent.

State has also been weakened by a changing world. The once-bright line separating foreign policy from domestic policy has blurred, bringing more federal agencies into the fray and creating more competition for influence. At the same time, modern communication technology has negated State’s traditional source of power: its control over the flow of information between foreign capitals and Washington. Any White House that can access the same information as State (be it by reading diplomatic cable traffic, accessing CIA reports, or watching events unfold live on CNN) and that can communicate directly with foreign capitals can effectively disregard the department.

But even if State had been blessed with strong leadership and the world had stood still for the past dozen years, the department still would be in decline. Decades of effort to “improve” the way America makes foreign policy have left the department weak and disorganized. Reformers have trimmed State’s responsibilities, either because they thought it ignored certain issues or because they believed the issues could be better tackled elsewhere. The U.S. Agency for International Development was created to ensure U.S. support for development, for example, and the Office of the Special Trade Representative was established to make sure business interests would not be sacrificed in the conduct of diplomacy. At other times, State’s responsibilities have been transferred elsewhere, as when the Treasury Department began to represent the United States at international financial institutions and the Foreign Commercial Service moved to the Commerce Department. The merger of the U.S. Information Agency and Arms Control and Disarmament Agency back into State in 1999 was a small step toward reversing a decades-old trend of whittling away State’s authority.

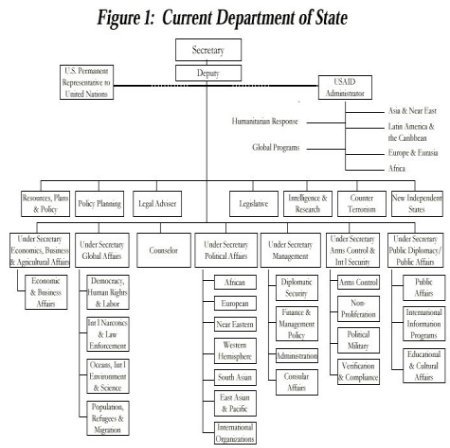

Of equal consequence have been reforms that have established new functional bureaus along side the traditional regional bureaus. Reformers argued that these new bureaus were needed to overcome the Foreign Service’s supposed preoccupation with traditional bilateral political relations and aversion to developing functional expertise. As a result, there are now bureaus and bureau-like offices for issues such as human rights, narcotics, the environment, economics and business, political-military affairs, refugees, and counterterrorism. The reintegration of ACDA and USIA into State added another six functional bureaus to the mix. Today, 13 of the 20 policy bureaus and offices in State concentrate on functional matters (see figure 1).

|

| CLICK ANYWHERE IN CHART TO ENLARGE. |

Rather than making things better, these reforms have accelerated State’s decline. Stripping an organization of its responsibilities seldom makes it more effective, and no employees feel empowered watching their duties go to others. Meanwhile, the proliferation of functional offices has made State far more difficult to manage. Changes have been made piecemeal over time, without any thought to their cumulative impact. The result is an organizational structure that no one would replicate if they were starting from scratch. Overlapping jurisdictions abound. Regional bureaus build up their own staff of functional experts rather than rely on those in the functional bureaus. This unnecessary duplication breeds infighting. Policy positions emerge slowly, if at all. When they do emerge from the labyrinth of competing interests, they often emphasize process over substance.

More important, the proliferation of functional offices creates problems because these offices work at cross purposes with the department’s organizational culture. The experience of the past two decades makes clear that creating a functional office is easy. But turning that office from a symbolic gesture into an effective voice in policy making is hard. The Foreign Service continues to think in terms of countries, FSOs still have few incentives to develop a functional expertise, and regional offices remain the department’s most prestigious. Functional and bilateral issues are therefore seldom integrated into a coherent policy whole.

The cumulative effect of these changes is a stove-piped organization in which power lies in regional bureaus that have no organizational incentive to make functional issues a priority. After all, those issues are handled elsewhere in the building. Accountability suffers and buck-passing becomes common because no one bears responsibility for policy that has both functional and bilateral elements (as almost every issue does). Worse yet, a stove-piped organization by its very nature both rewards obstinacy by subordinates and the overwhelms the secretary of State with work. Regional and functional offices have few incentives to settle differences among themselves, so they routinely kick disputes up to the Seventh Floor for the secretary or deputy to settle.

Back to the Regions

Organizations succeed over time by building structures that harness the power and ability that resides in their people. But not every structure will do. Structural change needs to work with rather than against the prevalent culture of the organization. In State’s case, that means abandoning the premise that Foreign Service officers are an obstacle that needs to be circumvented. Instead, reform must build on the unique strengths and talents of the diplomatic corp. To that end, the Hart-Rudman Commission has endorsed replacing a structure that maintains an artificial separation of regional and functional issues with one that integrates the two.

|

| CLICK ANYWHERE IN CHART TO ENLARGE. |

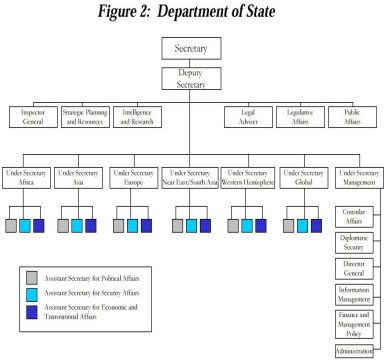

Figure 2 shows what an integrated, regionally-organized State Department would look like. There would be five regional under secretaries, one each for the world’s five major regions (Africa, Asia, Europe, Near East/South Asia, and Western Hemisphere.) Each under secretary would be responsible for integrating and coordinating all aspects of foreign policy in the region and would oversee three functional bureaus—each headed by an assistant secretary. The assistant secretary for political affairs would handle essentially the same duties as the regional assistant secretaries in State’s current structure. The assistant secretaries for security affairs and for economic and transnational affairs would oversee functional offices that currently now operate in isolation from bilateral relations.

In addition to the regional under secretaries, an integrated, regionally-organized State Department would also have under secretaries for management and global affairs, both of which currently exist. The under secretary for management’s duties would remain unchanged. (This office might be streamlined, though, perhaps by cutting the number of assistant secretaries now reporting to it.) The under secretary for global affairs’ portfolio, however, would be vastly different from its current role, which is to oversee functional concerns like human rights and environmental issues. Rather, this under secretary would be responsible for integrating and coordinating all the department’s activities in multilateral forums and all those matters that occur across regions. The global affairs under secretary would, like the regional counterparts, be assisted by assistant secretaries for political, security, and economic and transnational affairs. Thus, the assistant secretary for global political affairs would handle U.S. diplomacy in international organizations, including the United Nations; the bureau for global security affairs would be responsible for the global aspects of issues such as weapons nonproliferation, counterterrorism, and peacekeeping; and the assistant secretary for economic and transnational affairs would oversee issues such as humanitarian emergencies, international economic policy, democracy, and the environment.

These structural reforms would make the under secretaries pivotal decision makers. Because they must integrate regional and functional issues as well as oversee development aid, security assistance, and democratization programs, it is essential that they have strong managerial expertise. Although FSOs are often derided for ignoring management, many do have the required skills. Those that have served as ambassador or deputy chief of mission, especially at America’s larger embassies, have considerable managerial experience. Moreover, political appointees with established managerial expertise would be appropriate for the under secretary positions.

To make the most of a regionally-organized State Department, two other structural reforms are necessary. The first is to reverse the trend over recent decades to strip authority away from the department. The process begun by merging ACDA and USIA back into the department should be continued by completely integrating AID’s activities, programs, and expertise into State. (Sen. Jesse Helms’s proposal to substitute an independent foundation in AID’s place is a step in exactly the wrong direction. It would further separate foreign assistance efforts from U.S. foreign policy considerations.) This integration can be accommodated because AID itself is organized primarily along regional lines. In addition, the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations should, like all American representatives to international organizations, be folded back into the department’s structure and report to the secretary of state through the under secretary for global affairs. Finally, President George W. Bush and Secretary Powell should severely curtail the use of special envoys and commissions that operate independently of State or outside its regular channels of operation. Such innovations may provide political cover against charges that the administration is ignoring a foreign policy issue critical to a vocal constituency, but they undercut the nation’s diplomatic establishment. In those limited cases where it makes sense to designate a particular person to handle high profile issues, the president should appoint people from within the State Department rather than outside it.

The second step is to centralize responsibility for planning, budgeting, press, legislative, and legal affairs in offices that report directly to the secretary of State. A new office for strategic plans and resources should be formed by merging the Policy Planning staff and the Resources, Plans, and Policy Office and expanding their activities. This new office would be charged with developing the department’s strategic plans, matching these plans with its resource requests, and overseeing resource allocation among State’s assistance programs. At the same time, legislative and public affairs activities that are now attached to individual bureaus should be centralized in single bureaus reporting directly to the secretary. This would relieve individual bureaus of the temptation to “go it alone” and increase the prospects for coordinated policies.

Six Advantages of Reform

Rather than designing ad hoc structures to circumvent the perceived failings of the Foreign Service culture, an integrated, regionally-organized State Department will harness them together to produce a more coherent foreign policy-making process. This restructuring recognizes that U.S. policy deals with countries and regions, not functions, and that the challenge in a globalizing world is to integrate regional and functional concerns into a sensible whole. It will do so in six ways.

- First, incorporating functional offices within regional bureaus forces the State Department to integrate political and functional issues further down the chain of command. Instead of being an afterthought—or worse yet, an intrusion by another of State’s tribes—functional issues would become the property of regional offices and therefore their responsibility. This would make it possible to identify key policy trade-offs early in the process rather than late.

- Second, placing functional offices under regional under secretaries will elevate the status of functional issues within the department. This runs counter to the conventional wisdom that functional issues benefit from having their own under secretaries (an idea that will lead some to suspect a regionally integrated State Department is simply a ruse for giving global issues such as human rights and the environment a lower priority). But that view mistakes existence for effectiveness. As long as functional issues are kept separate from bilateral relations, they will be a poor step-child in State’s decision making process. That structure institutionalizes the incentives that FSOs have to avoid developing functional expertise. All that changes in a structure in which functional concerns are integrated into regional ones. Rather than seeing assignment to a functional desk as a career detour, suddenly it will become a new route to the top of the regional hierarchy, especially because in some regions security or economic and transnational affairs are likely to be where the action is at.

- Third, an integrated, regionally-organized State Department makes people accountable for what they do. Today, the State Department lacks accountability because so many policies are split between regional and functional offices. By contrast, in an integrated, regionally organized State Department, responsibility is unified in the offices of the regional undersecretaries. They will become the point person for what happens in their region, and just as important, they will have the authority and resources to integrate issues. When presidents, members of Congress, and secretaries of State want to know why U.S. policy toward, say, China has glossed over human rights concerns, they will know whom to call to account. Moreover, contrary to claims that regional issues will inevitably swamp functional ones, the fact that regional under secretaries will have no one to pass the buck to will give them powerful incentives to tackle functional issues and not let them languish.

- Fourth, reorganizing State along regional lines and integrating AID into the department will reduce duplication. The number of under secretaries falls to seven with the elimination of the counselor (an under secretary equivalent) and the post of AID administrator. The number of policy bureaus (excluding management and support functions) will be reduced from the 26 bureaus currently in State and AID to 18 overall. Bureau-like entities such as the Office of Coordinator of Counterterrorism and ambassadors at large for issues like war crimes, international religious freedom, and women’s issues will also be abolished. Finally, regional reorganization will eliminate duplication that now exists between regional and functional bureaus.

- Fifth, integrating AID into State will enable the United States to structure more effective foreign assistance programs. In a globalizing world, diplomacy is integral to assistance programs and not something to be held at arm’s length. When it comes to development aid, the crucial roadblocks are created by governments that pursue unwise and often corrupt policies. Persuading them to do otherwise is the job of U.S. diplomats. The demand for humanitarian assistance has grown as a result of man-made and natural disasters. Most of these disasters have their roots in deliberate choices by foreign governments—whether it be to wage war or to pursue land-use policies that make famines likely—so it makes sense to unite America’s assistance programs with its foreign policy. Moreover, the State Department already has considerable experience in this area because of the work of its Bureau for Population, Refugees, and Migration. Finally, assistance programs to advance human rights and democracy are inherently tied to America’s diplomacy and will be best served by being integrated within a single entity responsible for all of America’s foreign policy.

- Sixth, and most important, a regionally organized State Department will strengthen the secretary of State. It does so in part by reducing the demands on the secretary’s time. Pushing responsibility for integrating functional and regional issues down the chain of command will enable the secretary to devote less effort to refereeing among competing under secretaries and more effort to identifying and working on the department’s top priorities. And when disputes do get kicked up to the Seventh Floor, they are more likely to involve important issues that merit the secretary’s attention. Integrating AID into State and eliminating special envoys should also give the secretary more time to focus on the department’s priorities simply by reducing the number of people reporting to him or her.

Equally important, a regionally oriented reorganization will strengthen the secretary of State’s ability to manage the department. Not only will the secretary now have accountable under secretaries, but the new strategic plans and resources office will act as the secretary’s brain trust, developing the department’s overall policy goals and priorities. It will also enable the secretary to monitor how well the global and regional under secretaries are using resources and to identify how resources might be shifted across regions or into or out of global affairs to the betterment of U.S. foreign policy.

Making it Happen

Proposals to reform the State Department, including those the Hart-Rudman Commission supports, are sure to be greeted by the department’s employees with the disdain that has met similar efforts in the past. The cut blue ribbons that adorn the lapels of many a pinstripe suit in Foggy Bottom graphically illustrate what much of the Foreign Service thinks about reform commissions. The hope, expressed at the time of Secretary Powell’s appointment, that with strong leadership and more funding all will be well so long as the State Department and its people can do their jobs without outside interference very much prevails.

Yet, notwithstanding these hopes and expectations, Secretary Powell will soon realize (if he has not already) that good leadership and more money will only get you so far. A dysfunctional organization will remain a major impediment to translating good ideas into effective policyone that will loom ever larger as time goes by. And as a man who has run his share of organizations, Powell ought to be attracted to the idea of reform. Indeed, his effectiveness as secretary of State will depend on it.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

How to Revitalize a Dysfunctional State Department

March 1, 2001