Editors’ Note: Shibley Telhami writes that some of the findings of his latest poll on American public attitudes on issues related to Israel and the Middle East were striking, underpinned by demographic changes in America, especially within the Democratic Party. Since then, these observations have become conventional wisdom. This article originally appeared on

the Washington Post

‘s Monkey Cage blog.

A year ago, I wrote an article with Katayoun Kishi on this website about the emerging partisan divide in American public attitudes on issues related to Israel and the Middle East. Some of the findings were striking, underpinned by demographic changes in America, especially within the Democratic Party. Since then, these observations have become conventional wisdom, thanks in large part to Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s plunge into our political divide over the Iran nuclear deal.

But is there something more to what appears to be a deep party divide?

My latest poll suggests something particularly revealing: if one sets aside the Evangelical Republicans—who constitute 10 percent of the population and 23 percent of the Republican Party—many of the differences between Republicans and the rest of the country disappear on matters related to Israel and diminish with regard to Islam and Muslims. In particular, it turns out that Israel is not so much a Republican Party issue as much as it is an issue of Evangelical Republicans specifically.

First, a word about what I mean by “Evangelicals.” In the discourse, including my own analysis of previous polls, Evangelicals were lumped together with “Born-Again Christians.” While the two groups are often perceived as similar, the practical reason for this grouping was to obtain a bigger sample—roughly a quarter of all respondents in a national poll when combined—enabling better statistical analysis.

In my latest Sadat Chair/UMD poll—in cooperation with the Program for Public Consultation, fielded Nov. 4-10 by Nielsen Scarborough—I did separate the two groups. This was possible because we oversampled for Evangelicals and Born-Again Christians, based on how respondents chose to identify. In all, we had a significant combined sample of both groups of 1,074 respondents, allowing for far better demographic analysis. It turns out that, while those who identify themselves as Evangelicals overwhelmingly also identify themselves as Born-Again Christians (88 percent), the opposite is not true; only about half of Born-Again Christians identify themselves as Evangelicals as well. Overall, 13 percent of Americans identify as Evangelical and 11 percent as non-Evangelical Born-Again Christians.

More centrally, Evangelicals and non- Evangelical Born-Again Christians have different demographic makeups and different outlooks. For example, though 75 percent of Evangelicals are Republican, only 30 percent of non-Evangelical Born-Again Christians are Republican, with 38 percent of them identifying as Democrats. While Evangelicals are overwhelmingly white, non-Evangelical Born-Again Christians include 20 percent African Americans and 10 percent Hispanics. Policy-wise, Evangelicals are more pro-Israel than non-Evangelical Born-Again Christians.

Since we had a significant sample—586 respondents – of Evangelicals, we limited our analysis to this group, which makes up 23 percent of the Republican Party—making Evangelical Republicans 10 percent of the U.S. population.

If one sets aside this group within the Republican Party, Non-Evangelical Republicans start looking like the rest of the American population.

Let’s start with examples of the overall deep partisan differences on Middle East issues, based on the latest poll. While 51 percent of Democrats have favorable views of Islam, only 26 percent of Republicans feel the same. While 45 percent of Republicans want the United States to lean toward Israel in its diplomacy, 75 percent of Democrats and 80 percent of Independents want the United States to lean toward neither side. While 40 percent of Republicans say a candidate’s position on Israel matters “a lot” when they vote for president or Congress, only 14 percent of Democrats say the same. 43 percent of Republicans would want the United States to vote against a possible U.N. resolution endorsing the establishment of a Palestinian state; only 15 percent of Democrats and 13 percent of Independents say the same.

There are also issues for which the differences across party line are minimal: variation on supporting one-state vs. two states are barely outside the margin of error; and, in the absence of a two-state solution, a majority of each party endorses the Democracy over Jewishness of Israel, 82 percent among Democrats, 74 percent among Independents, and 62 percent among Republicans.

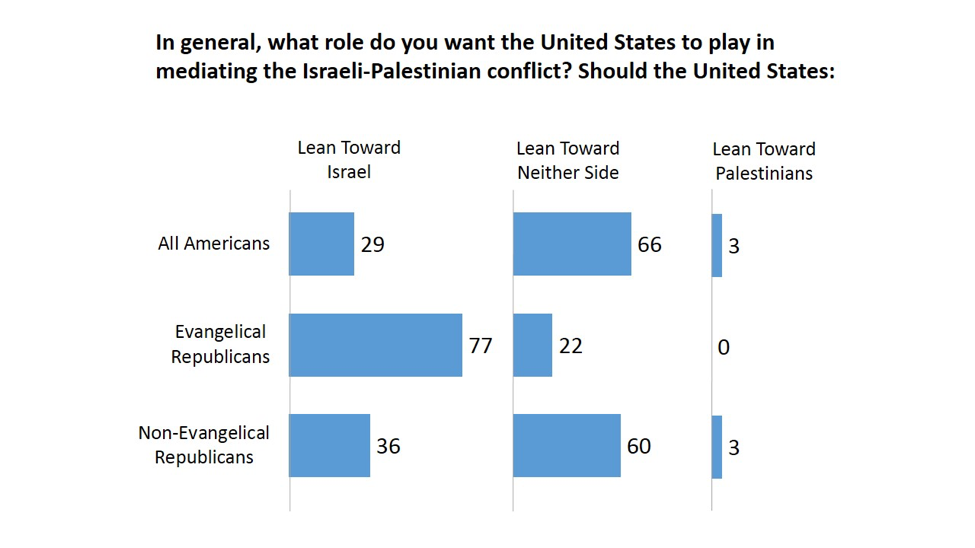

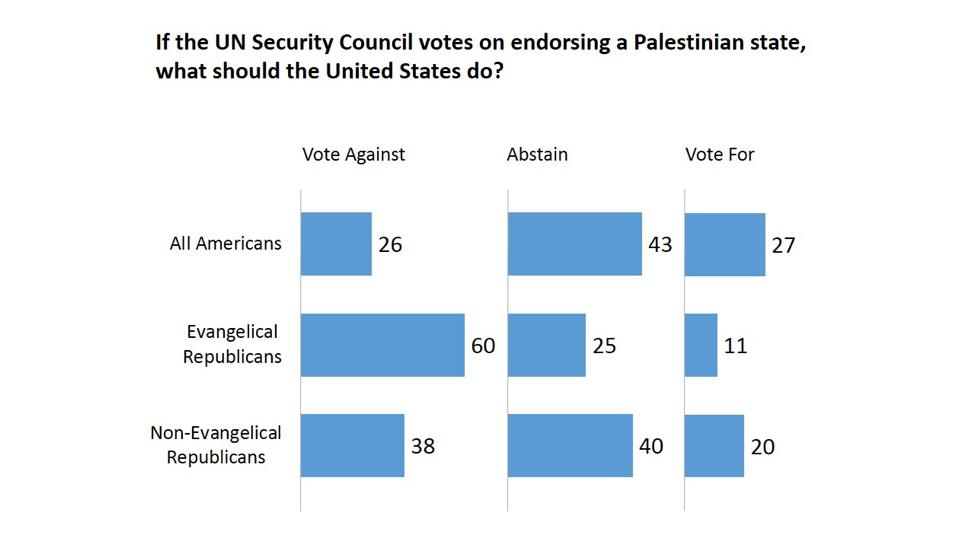

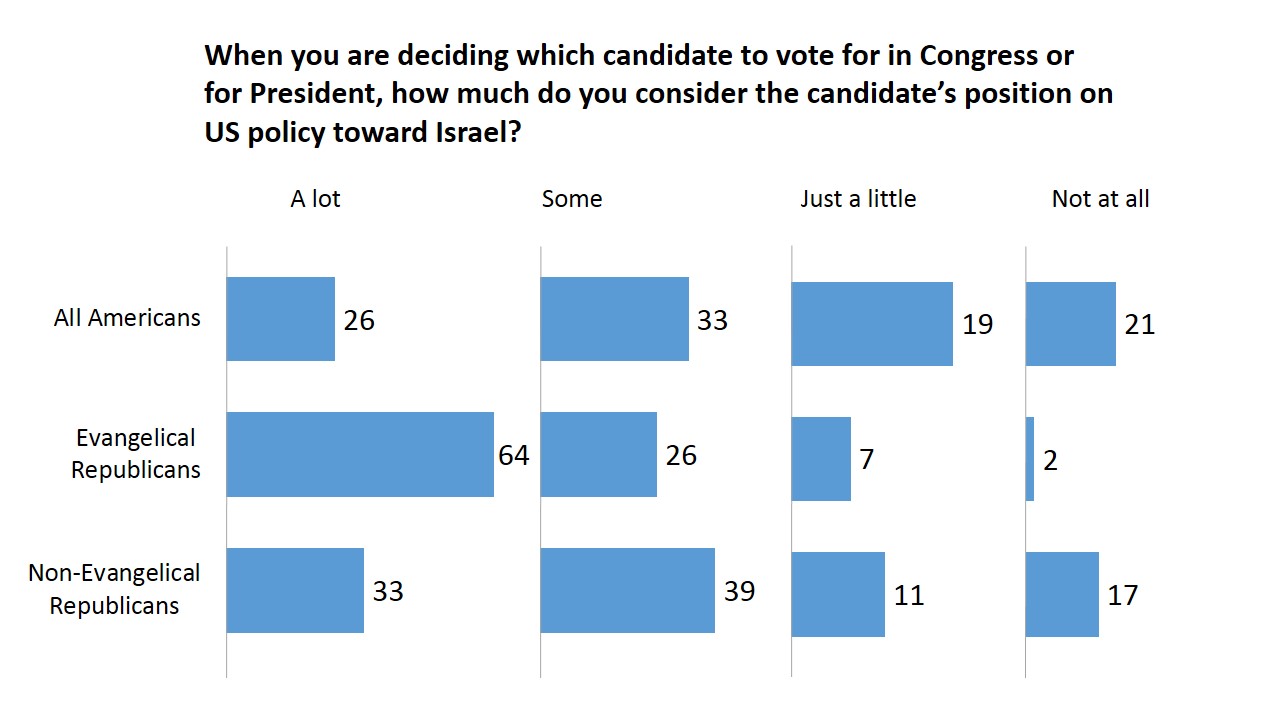

However, the differences between parties narrow substantially when one sets aside Evangelical Republicans, and the Republican position starts looking more like the rest of the country on many issues. Here are a few examples.

Regarding the importance of a candidate’s position on Israel when voting, 64 percent of Evangelical Republicans say this matters “a lot” compared with just 33 percent of non-Evangelical Republicans and 26 percent of all Americans.

Similarly, while 77 percent of Evangelical Republicans want the United States to lean toward Israel, 36 percent of non-Evangelical Republicans, and 29 percent of all Americans say the same.

When considering a possible U.N. resolution, 60 percent of Evangelical Republicans want the United States to vote against a possible resolution endorsing a Palestinian state, compared with 38 percent for non-Evangelical Republicans, and 26 percent of all Americans.

Similarly, while 77 percent of Evangelical Republicans want the United States to lean toward Israel, 36 percent of non-Evangelical Republicans, and 29 percent of all Americans say the same.

When considering a possible U.N. resolution, 60 percent of Evangelical Republicans want the United States to vote against a possible resolution endorsing a Palestinian state, compared with 38 percent for non-Evangelical Republicans, and 26 percent of all Americans.

Attitudes toward Muslims, Islam, and the compatibility of Western and Islamic traditions also change significantly when one controls for Evangelical Republicans, though to a lesser extent. 53 percent of all Americans have a favorable view of Muslim people in contrast to 35 percent of Evangelical Republicans. In comparison, 44 percent of non-Evangelical Republicans have a favorable view, comparable to the favorable view of Independents 43 percent. Considering views of Islam in general, 85 percent of Evangelical Republicans hold an unfavorable view of the religion, and 70 percent of non-Evangelical Republicans hold unfavorable views. Furthermore, Evangelical Republicans are more likely—62 percent—than non-Evangelical Republicans—54 percent—to view Islamic traditions as incompatible with those of the West.

Two additional points are worth noting. First, even among Evangelicals some hold more intense views than others on Israel and the Middle East. Two particular variables tell this story: those who never listen to Christian Radio vs. those who sometimes listen to it; and those who never watch Christian television vs. those who sometimes watch it. Among Evangelical Republicans who sometimes listen to Christian Radio, 76 percent say that a candidate’s position on Israel matters a lot when deciding who to vote for in Congress or for President. However, for Evangelical Republicans who never listen to Christian Radio, only 46 percent say that a candidate’s position on Israel matters a lot. This gap widens when we turn from radio to television. 82 percent of Evangelical Republicans who watch Christian TV sometimes saying that a candidate’s position on Israel matters a lot compared to 41 percent who never watch Christian TV.

In short, much of the story of American partisanship on Israel policy, especially, boils down to the role of the 10 percent of Americans who are Evangelical Republicans. And even among this group, the intensity comes especially from that segment of the Evangelical population that listens to Christian radio or watches Christian television.

Are Evangelicals themselves changing?

Some early data suggest possible change: Young people tend to be somewhat less focused on and less supportive of Israel than older people. Among Evangelical Republicans, 51 percent of those who are 55 years of age and older are more likely to say that the Israeli government has too little influence on American politics and policies. In contrast, only 27 percent of 18- to 34-year-olds feel that the Israeli government has too much influence. Older Evangelical Republicans are also more likely to blame Palestinian extremists for the violence between Israelis and Palestinians. 57 Percent of Evangelical Republicans 55 years and older believe that Palestinian extremists are most responsible whereas only 33 percent of 18- to 34-year-old Evangelical Republicans believe the same.

Whether these trends continue among Evangelical Republicans is hard to predict. In the meantime, it is easy to identify one of the key sources of the hardline positions taken by Republican candidates for president on Israel.

Commentary

How to (almost) eliminate the U.S. partisan divide on the Middle East

December 17, 2015