This town ... they were gonna roll up the streets. There were houses for sale on every block. The influx of immigrants, it absolutely saved this town.

Lorraine Brasel

Since the 1990s, Beardstown, Illinois — official population 5,800 — has experienced steady immigration due to the meatpacking industry, breathing new life into this once declining town. Now a multicultural community with residents from over 30 countries, newcomers have integrated throughout neighborhoods, revitalized storefronts, and enriched local schools. In this episode, Tony Pipa explores how this small Midwestern town has learned to embrace change and built a vibrant downtown, and how policy changes and the national narrative about immigration are affecting this rural place.

Featuring:

- Lorraine Brasel, Retired instructor, Western Illinois University

- Jamie Chapman, General manager, CherryRoad Media, Beardstown, Illinois

- Brian Deloche, Beardstown, Illinois

- Maggie Hea, Beardstown, Illinois

- Christian Kimungu, Beardstown, Illinois

- Buffy Tillitt-Pratt, Real estate broker, Beardstown, Illinois

- Armando Trujillo, Beardstown, Illinois

- Katie Vitale, City Clerk, Beardstown, Illinois

Want to learn more? See Tony’s interview with Rachel Perić of Welcoming America to explore what rapid demographic change means for small-town life.

Transcript

[sounds of a fair]

PIPA: Ah, the sounds of a small-town fair. The rides … burgers on a hot grill.

FESTIVAL EMCEE: Well, we’d like to take just a second to welcome you to the 2025 Beardstown Fall Fun Festival. Thank you so much for all your support this weekend. We hope you’re having fun. Wasn’t that a great band? That was a nice way to spend a Sunday afternoon.

[music]

PIPA: You know, the Fall Fun Festival has been happening here in Beardstown, Illinois, for more than 70 years. It’s a community celebration that’s a tradition, like those in many rural places across the country. But it doesn’t take long to see that this place is a little different than any other Small Town USA. Multiple taco trucks, the food and crafts from the Caribbean, and offerings from lots of other places around the world. In fact, Beardstown is a place where the local school district welcomes students from 30 different countries speaking 18 different languages and dialects.

BRASEL: This town was, I mean, they were gonna roll up the streets. There were houses for sale on every block. The influx of immigrants, it absolutely saved this town.

PIPA: In this episode of Reimagine Rural, I’m visiting Beardstown to learn how immigrants have brought a new kind of life and vitality to this Midwestern town, and what the future might hold for them and this place.

[music]

I’m Tony Pipa, a senior fellow in the Center for Sustainable Development at the Brookings Institution, and your host for the podcast, where I talk to local people, capture their stories of the positive changes unfolding in their hometowns, and explore the implications and the intersections with public policy.

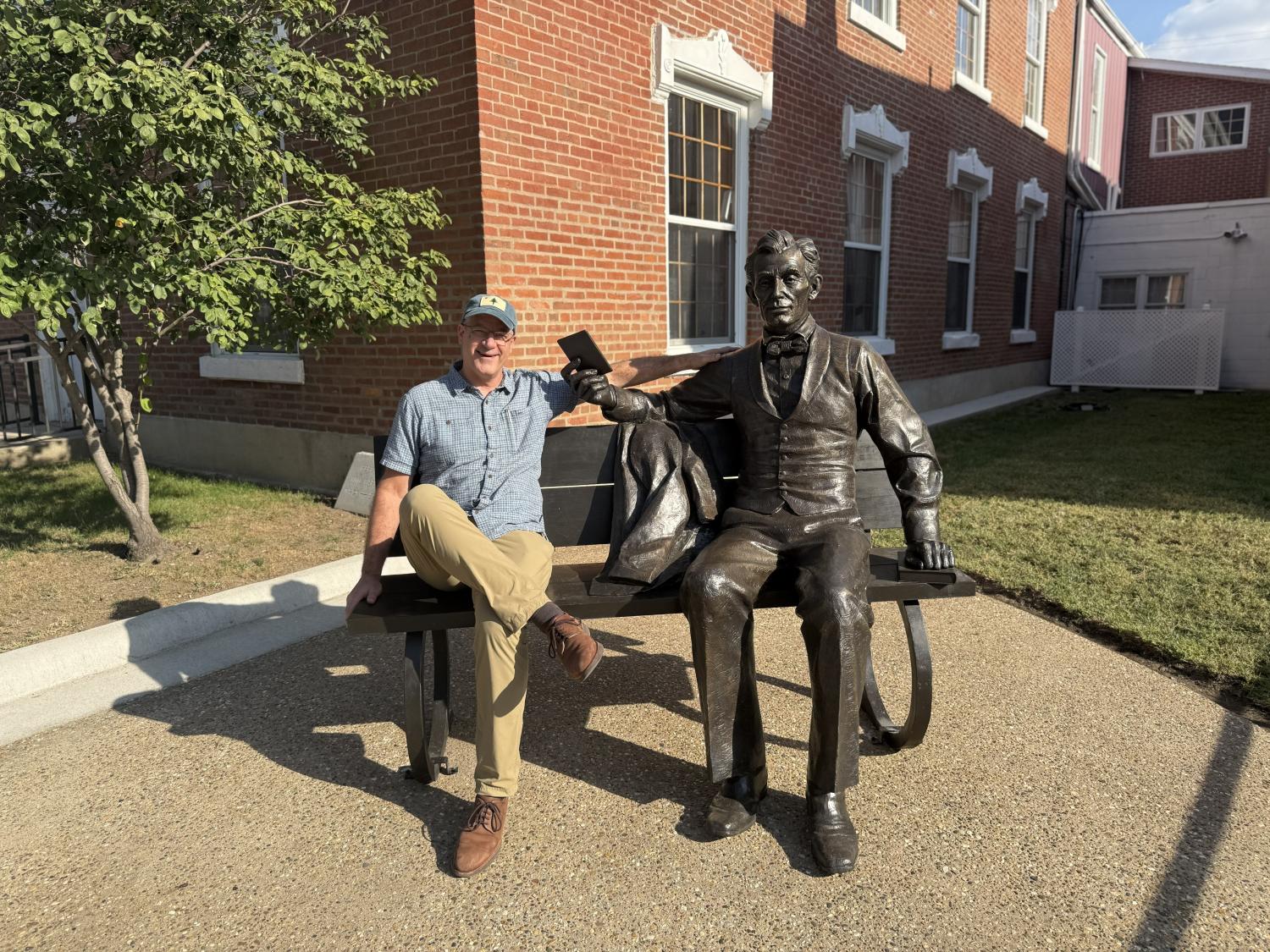

Beardstown is in west central Illinois, along the Illinois River, about two hours north of St. Louis, Missouri. Abraham Lincoln made a name for himself here defending Duff Armstrong in the famous Almanac Trial — it’s a good story to look up if you don’t know it. And the town is famous for having the only courtroom still in operation today where Lincoln practiced law. It’s the kind of quintessential American history that you often find in rural places.

In the mid-19th century, Beardstown earned the nickname “Porkopolis,” and was once the largest center of meatpacking in the country. That industry has its own unique history — one that’s traditionally been dominated by immigrant labor.

[music]

And true to form, since the early ‘90s, the local meat processing plant has attracted a wide range of newcomers who have since put down roots. The schools and churches have an unmistakable multicultural flair, and immigrants have opened several businesses downtown in storefronts that had been sitting vacant.

This is Katie Vitale, Beardstown’s city clerk.

[3:11]

VITALE: We have an African grocery store on our square. We have a Hispanic bakery. We have a Cuban church on the corner. We have Alondra’s, a Hispanic hairdresser here in town. We have a Haitian grocery store that’s about to open. We have four Hispanic grocery stores.

PIPA: Like many other rural towns across Illinois, Beardstown leans conservative. It’s in Cass County, which in 2024 voted overwhelmingly for Donald Trump. At the festival, at a table on the town square behind the Republican Party’s tent, I caught up with Buffy Tillitt-Pratt, a longtime real estate broker whose dad was mayor in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Buffy’s had a pulse on the demographic changes in the county as part of her work.

[3:54]

TILLITT-PRATT: On the sign at the edge of town it says 5,800 population. Now, we have many Hispanics in town who didn’t feel comfortable talking to the Census takers, and we have learned from the schools and the registration of the children that our our population is closer to 7,000.

PIPA: City officials familiar with water usage suggest the population might even be higher than that.

[music]

Most of the folks we talked to remembered the late 1980s as a watershed moment in Beardstown’s immigration story: Oscar Mayer’s meatpacking plant was the town’s largest employer when it closed in 1987 after 20 years in business here. More than 600 people in Cass County lost their jobs.

A subsidiary of the agricultural conglomerate Cargill entered the picture that year and reopened the plant, offering pay that was almost 25% less than before. The company hired locals but struggled to keep a consistent workforce at those wages. That’s when they started hiring immigrants

Here’s Lorraine Brasel, a retired ESL instructor at Western Illinois University. You heard from her at the top of the episode. We spoke in the yard in front of her home in Beardstown.

[5:20]

BRASEL: One of the things that happened with Oscar Mayer was the rate of injuries and carpal tunnel syndrome and all those things. Well, with an immigrant population, that didn’t matter because those people were not making claims. And so we had this huge influx very quickly of mostly people from Mexico to work there.

PIPA: Brian Deloche was a police officer for two decades in Beardstown. He’s retired now, but Brian has worn a lot of hats over the years, mostly in public service. And during my conversations in town, he was kind of acknowledged as the unofficial historian of Beardstown. He now runs the food pantry, and he’s also a military veteran, former editor and now occasional newspaper columnist, former school bus driver, and a hobbyist photographer.

[6:10]

DELOCHE: Beardstown was a community where everybody knew everybody.

PIPA: Brian’s also worked in radio. Can you tell?

DELOCHE: You knew the people that lived on your street, you knew the people that you went through school with. I knew all the people that I delivered newspaper to. Most of the families, adults, grandparents, they stayed. Somebody would be in a house, and they’d be in that house for 20, 30, 40 years.

There was a lot of, I wouldn’t exactly say pushback, resentment would be too strong. But it’s like, why? Why are they coming here? What are they doing here? So neighborhoods began to change, and the community began to change with it. There was racism. Most of it I would say was thinly veiled back then. From our surrounding communities, there was a kind of a condescending attitude. They started talking about Beardstown as being “Little Mexico,” because this is where people were landing.

PIPA: The new residents attracted unwanted attention from beyond the county. In the mid-20th century, Beardstown was known as a sundown town.

DELOCHE: If you were a person of color in this community, it meant get out of town by sundown. You are not welcome here. That is no longer the case. I’m glad that that no longer exists.

PIPA: It was around this time that Lorraine Brasel met her now ex-husband, an immigrant from Mexico. She was teaching ESL classes and was attuned to the mounting tensions around town.

Unrest came in 1996 at a local Mexican bar. A young woman in town had been dating a white man from an established Beardstown family, but then she got involved with a Latino man, who was an employee at Cargill. It got violent — the white boyfriend and his friends beat up the Latino man, who left the bar and returned with a gun.

[8:18]

BRASEL: And so he shot one of the people, actually, not the actual person he was looking for, but he shot one of the group that had beaten him. And then a very strange situation, he got away. He swam across the river, he realized there was no place over there. He swam back across the river. He went to some people’s houses who didn’t know what had happened, you know, was still in the middle of the night, asked them to take him to the airport in St. Louis. And they did. So he got out of the country that night, flew out to Mexico. That really enraged a lot of people and there was a lot of trouble at that time.

PIPA: After the murder, someone set fire to a 6-foot-high makeshift cross in town, and a week later, the bar went up in flames, too. There were rumors that the Ku Klux Klan, which a year earlier had staged a protest in a neighboring county, was coming to town. Lorraine and others were ready to restore some peace.

[9:19]

BRASEL: It was crazy for a while. Everybody was scared. And we had the FBI in town and lots of people coming in town, lots of news also. We formed a group called Beardstown United. We had an organizational meeting, we had hundreds of people there, immigrants, and we built a float together for the parade. And the float won first prize. It was a group called Beardstown United of Americans and Immigrants. And it was a beautiful bridge that opened and closed.

[music]

We had an architect working on it and everything. Because a lot of these people have come with advanced degrees and then they have to work at the slaughterhouse.

[music]

PIPA: And indeed, peace did come. Lorraine’s then-husband opened a Mexican grocery downtown, Su Casa — the first of its kind in Beardstown. It’s still open, but they have lots of competition these days from a few other stores. I stopped by to take a look around.

¿ Tienes problemas de araña roja y mosquita blanca en tu cultivo? Hola Quimia tiene la solución. Evante es un producto…”

PIPA: Lorraine continued teaching, too.

[10:29]

BRASEL: I never thought I would teach ESL in this town, you know, that was just amazing. When the influx came in I had been teaching composition in Springfield as a part-time job with my other job. And at the time we didn’t even have a school. We operated out of the church and different buildings, and I had to go get my own funding from Cargill at the time.

PIPA: Now, Lincoln Land, the local community college offers a variety of free ESL classes — in-person and online — covering reading and writing skills, plus other topics like technology, U.S. culture, and civics.

One fascinating, and important, detail about Beardstown: newcomers didn’t settle in their own little enclaves on the outskirts of town, walled off from their white neighbors as happens so often in so many places. Here again are Buffy, the real estate broker, and Katie, the city clerk.

[11:31]

TILLITT-PRATT: They integrated into the entire town. They lived in every block. Wherever there was a house for sale, they would buy it and live in it. And that taught our older Beardstown people to get to know them better and to trust them because, you know, the grandma would be pulling weeds in the flower garden and the little kids would come and say, can I help you? And it taught the original people in Beardstown, oh, look, they’re people. They’re just like us. And it was really the best thing that ever happened.

[12:05]

VITALE: So, when I moved here, my block of eight houses had all Caucasian people living in them. Right now, my block has four, so half, which is kind of the trend that we’ve seen is that the immigration population has pretty much doubled. And so, I mean, even if you look at our statistics with our school and things like that, I mean you can see that Caucasians are the minority.

BRASEL: All of my neighbors are either Dominican or African or Mexican. You know, it’s just such a mix. There’s no neighborhood segregation. That’s what I love about Beardstown.

PIPA: I talked to one of those neighbors, Christian Kimungu, who invited me into his apartment to chat. He was an electrical engineer in his native Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, before he came to the United States through an immigration lottery program. A friend in the DRC connected Christian with his brother, who lived in Champaign, Illinois.

From him, Christian learned about JBS, the world’s largest meat processing company, which is headquartered in Brazil, but had acquired Cargill’s pork operations in Beardstown ten years ago. The Beardstown campus produces seven million, 8-ounce servings of pork per day. The work can be grueling, but it’s consistent.

[13:30]

KIMUNGU: So he took me over here to Beardstown. And the first time when I got here, it was like, oh, it’s a small town, quiet. And then I introduced my application to JBS. And then they called me and then I start working down there.

When I came the first time when I came in Beardstown, I was not speaking English the way you are speaking to me. No. Just French. I was not able to to have, like, a conversation with some people. And myself, I went to ESL to learn just how to speak and to talk.

PIPA: Kinshasa, where Christian comes from, is huge, by the way — it’s one of the largest cities in the world. So I wondered what about Beardstown would appeal to him. Christian said his new friend made what seemed like a good case: Champaign has more than 90,000 people — and though it’s nowhere near as big as Kinshasa’s population of over 17 million, he worried Christian would get lost in the mix in Champaign. He urged him: Try out this small town first. Throughout our conversation, Christian talked again and again about how safe he feels in Beardstown.

[14:48]

KIMUNGU: Do you know in Africa you can send your kids to school, not in the capital, but somewhere else, and you cannot go back to pick them up. You don’t, you never know. I’m telling you the truth. The rebel they can just come to take your kids and go with them. They don’t care how old they are. They, they’re the little kids, 10, 12, gonna give them the gun to fight. So you cannot walk, even if in the capitol, you cannot walk, like after 10:00 p.m.

PIPA: Christian told me how one night, after 10 o’clock, he walked to get some food at a restaurant in Kinshasa and got hassled by the police, who stole his money and roughed him up.

KIMUNGU: I like, I like, like Beardstown because it’s a quiet town, too. No problem, no violence. Everybody knows almost everybody.

[music]

PIPA: So the place where most immigrants are coming to in Beardstown is JBS. And all across Beardstown, you can find evidence of their support. The signs entering town read “BEARDSTOWN, HOME OF JBS.” The company donated the soccerplex which bears its name. During the Covid pandemic, JBS donated to downtown revitalization projects.

VITALE: So at that time we got to redo the Beardstown Square. We redid the river walk. We made murals here in town. We redid all of the entrances into town with all of that money just to kind of give it a new life, so that people knew that we were still around.

PIPA: For a quarter-century Beardstown has hosted Fiesta Patrias in mid-September, a celebration of Mexico’s independence. Here’s Jamie Chapman, general manager at the Cass County Star Gazette newspaper. Jamie’s a lifelong resident of Beardstown.

[16:47]

CHAPMAN: You see everyone, young and old, I mean, people from my church I see there every year. Everybody celebrates it. And that shows, I think, how far we’ve came as a community, as accepting it and accepting the immigration.

PIPA: To illustrate what you hear Jamie saying, just listen to this audio from a video that Armando Trujillo made of last year’s event.

TRUJILLO: ¿Cómo se celebran las Fiestas Patrias en Beardstown, Illinois?

PIPA: He’s a recent graduate of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and a Beardstown resident. It’s quite the fiesta — dancing, pinatas, music, a parade, colorful traditional costumes — the works. But this year, the committee behind the event decided to cancel it.

[17:58]

TRUJILLO: My parents are part of the committee that throws that celebration, they didn’t throw the festival this year and they were not part of the parade this year as a protest for everything that’s been going on over at the government. It was a group decision done by the committee and hopefully something was said by it. Hopefully the the silence was felt.

PIPA: Lorraine feels as if the policy shifts in Washington toward strong immigration enforcement have caused fear in the community, and that it was a factor in the decision to cancel the fiesta.

BRASEL: I have never seen the fear that is just pervasive now. I mean, for the for the festival to be canceled, that just shows how afraid people are, the people who have legal documents.

PIPA: As a rationale for his administration’s strong stance on immigration, President Trump has suggested that immigrants are taking jobs away from American workers. But that hasn’t been the experience in Beardstown.

[19:08]

DELOCHE: Over the last 30 years, I’ve watched the shift in population and the workforce at JBS or Excel or Cargill or whatever name you wanted to put on it over the last 30 years. And the reason they have turned, those employers have turned to an immigrant-based workforce is because they couldn’t find people to take the jobs that they were offering for the amount of pay and benefits that they would receive. That is the simple truth of the matter.

[music]

Nobody that I know that had a job there was kicked out because we’re gonna replace you with somebody of color, we’re gonna bring in somebody to take your job. No, that’s not happening.

PIPA: Earlier this year, the Trump administration revoked the country’s humanitarian parole program that allowed residents of Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Venezuela to come to the United States for work. It’s the same program that brought Haitians to Springfield, Ohio, a situation that became such a major story during the election.

That program had allowed JBS and Dot Foods, a company less than half an hour away that is North America’s largest food industry redistributor, to sponsor hundreds of workers, many of whom reside in Beardstown. They all suddenly found themselves undocumented, and it’s hard to know what that’s going to mean for the town.

Despite the cancellation of Fiesta Patrias, Buffy Tillitt-Pratt’s church — Saint Alexius Catholic Church — held its own small Mexican Independence Day celebration. She thinks the suggestion that her neighbors are scared is overblown.

[21:07]

TILLITT-PRATT: There were non-documented people at this event, and they were not hiding. They were not afraid. They have been here, many of our undocumented people have been here 20 years. They have an I-10, they’re paying income tax. They were not hiding; they were celebrating Mexican Independence Day.

BRASEL: I mean, my ex-husband, he’s a naturalized citizen, but he has his doubts, you know. But he continues to go back to Mexico to see his family and says, I’ll risk it. But his wife who has permanent residency, she’s afraid to cross a border.

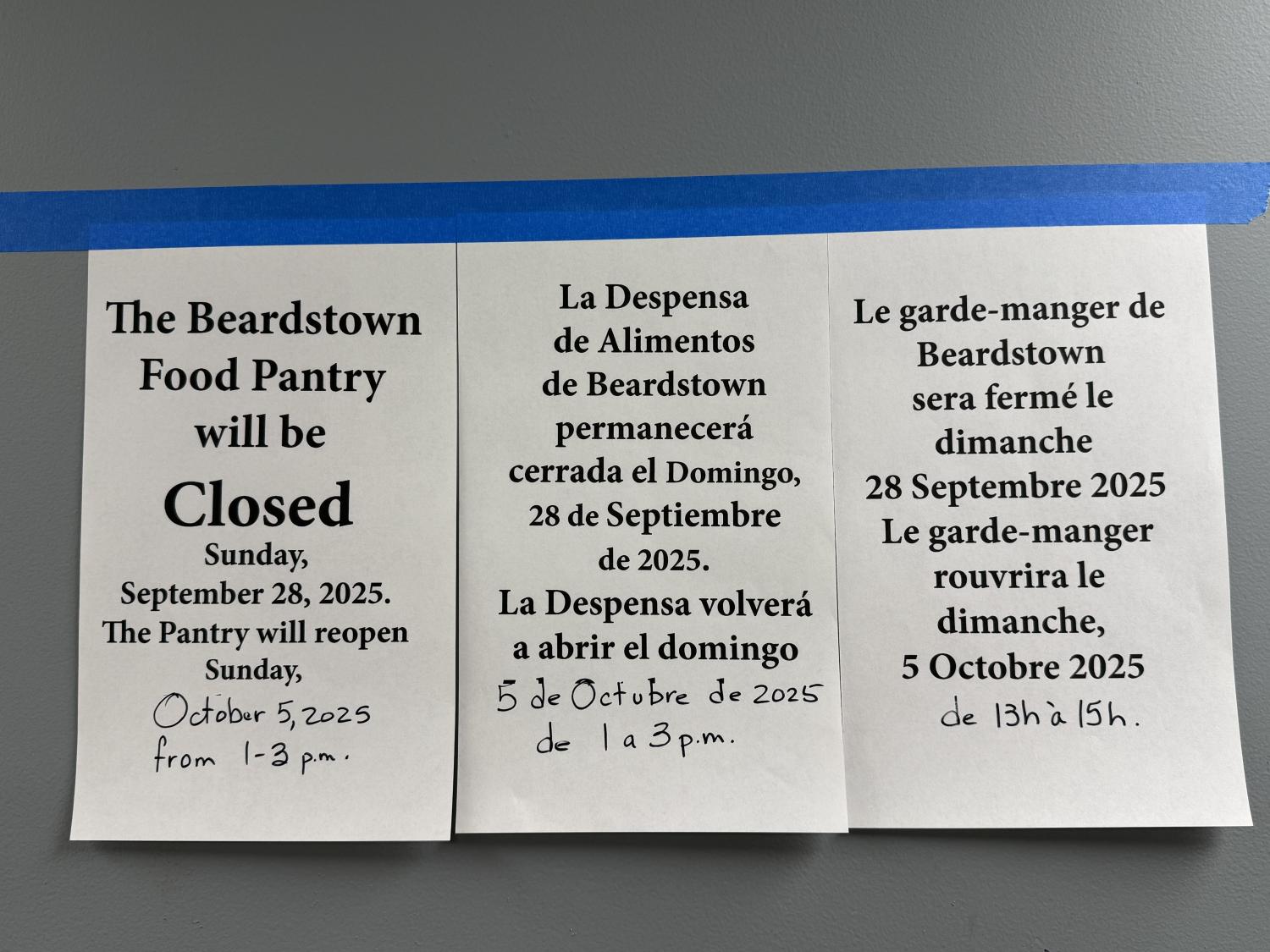

PIPA: Signs of Beardstown’s diversity are easy to find all across town. The Catholic church in town offers services in English, Spanish, and French. The school district posts social media announcements in those languages on its Facebook page. It is not unusual to walk around town and pick up snippets of conversation in all three languages.

[22:07]

DELOCHE: You don’t find this degree of diversity anywhere else. I would just about venture to say Beardstown may well be in its diversity makeup and its demographics one of the most diverse communities under 10,000 people anywhere in the United States, certainly in the state of Illinois.

PIPA: That diversity was a huge draw for Beardstown resident Maggie Hea when it came time to enroll her kids in public school.

HEA: I feel very lucky that my kids got to grow up in our little bitty town with so many cultures, because I feel like it prepared them to be more ready for the world. They go out into any society now and they’re comfortable with all the different cultures, all different types of people. They’re just so culturally competent and I feel blessed that they got to grow up in a place that taught them that.

PIPA: Here is Lorraine Brasel again, followed by Jamie Chapman, from the newspaper.

[23:19]

BRASEL: We would not have our high school if it weren’t for the immigrant community coming in. And I think people realize that. All the other schools have had to consolidate, and we’re still the Beardstown Tigers. And it has brought in talent. We have a soccer team now and they are great. And we have had some great football players. And, you know, it’s just helped school a lot.

CHAPMAN: When I was in high school, it was like, well, what’s soccer? I’ve seen it on TV some, but that’s something we kind of skip over and now it’s just huge. We have so many kids, you know, and it’s everyone you see. It’s the same thing. A little boy that was his whole family’s been born and raised here for a hundred years playing next to a little girl from Africa, next to a little boy from Haiti, you know, and it’s neat. Soccer’s huge for everybody.

PIPA: But a population as diverse as Beardstown’s needs resources in its schools — and that has presented some challenges.

[24:15]

DELOCHE: The change was rapid. And it became necessary for our school to district to implement English as a second language classes. They developed grant programs to accommodate the new immigrants. And so there was grant funding available for those programs. But the way the programs were structured, new computers went to the grant-funded programs and were not available to the people who were not part of the grant-funding programs. And that created resentment.

BRASEL: It has created some challenges, because our test scores are down, you know, it’s because there are a lot of non-English speakers. And so they have to have a bilingual program. But I think those those challenges have been outweighed by what we’ve gained in diversity.

PIPA: And like many rural towns across the country, Beardstown is faced with a major housing challenge. Everyone I talked to said so, including real estate broker Buffy Tillitt-Pratt.

[25:24]

TILLITT-PRATT: One of the constraints is the river on two sides of the town, swamp land on the other side of the town. You know, we don’t have the right direction to build. We have one way to build. The other is, as you all know, new construction’s getting totally out of reach.

PIPA: It’s not just the geography. Like its rural counterparts across the country, the housing stock is old and often not well-maintained, and the cost of building is prohibitive. Combined with the lack of new construction over the past decades, it makes things tough.

TILLITT-PRATT: I’ve sold real estate for 47 years. I have never seen prices like I am seeing now, and the reason for the prices is supply and demand. We have a little town that has 7,000 population, maybe has enough houses for six, and whenever a house would come on the market, people would buy it. The people that worked, the immigrants that were working out at JBS were making $25 an hour plus or minus. If they worked any overtime, they were grossing a thousand dollars a week. They wanted to buy a home, and they would pay the price because there wasn’t a lot of choice there.

PIPA: Here’s city clerk Katie Vitale again.

[26:45]

VITALE: That’s probably our biggest issue along with everybody else in this country. You know, we just have a shortage of housing. And with the shortage comes higher prices, and so people are getting gouged and they’re living in horrible places. So we as a city are trying to address that with, you know, stronger regulations and things like that to go in and inspect rental properties so that our citizens can have a safe place to live.

PIPA: Despite the cost challenges and age of the housing supply, immigrants have been a force in sprucing it up.

VITALE: The Hispanics, when they buy a house, they fix it up. I mean, they’ll take a $20,000 house and make it into a $70,000 house. So, I mean, they’re willing to do the work, which I always think is really cool.

DELOCHE: I think that our immigrant population to a large degree is serving us well. They’ve taken derelict buildings, derelict homes that were off the tax rolls, revitalized them, and put them back on the tax rolls. They’ve made homes that were eyesores pleasant to look at again.

[music]

PIPA: In Beardstown, at this point, the newcomers are woven into the community. When a place rented by many immigrants burned down a few years ago, Brian Deloche describes how the entire community rallied.

[28:04]

DELOCHE: A lot of people from the Congo and from Togo were in this building, in this small, old rundown hotel. And the hotel burned in the middle of the night. And a woman was rescued, was actually taken out of the building on a ladder truck. And her life was saved, and everything that those people had was lost. Everything was gone. All of their immigration documentation, all of their clothing, every personal belonging they had was destroyed in that fire.

PIPA: One of the people in that fire was Christian, Lorraine’s neighbor.

KIMUNGU: I was sleeping. And my building got on fire. I tried to save some people too, to get out from the building. We lost almost everything.

DELOCHE: Within 36 to 48 hours, the community had generated somewhere between $36,000 and $40,000 to find lodging for the people who were displaced in that fire. A lot of it came from the Congolese and the Togo communities that were here. But a lot of it came from our local churches who provided food, who provided water. One of the churches that was closest to it, to the fire scene, opened themselves up as a shelter. And this was a Hispanic church. And people poured in with money, and food, and blankets, and pillows to make sure that those people were taken care of.

KIMUNGU: Since then, I say they are my family now.

PIPA: And the culture of Beardstown’s family is simply global. Both Armando Trujillo’s dad and uncle are members of a local band that plays traditional Mexican music, and Lorraine Brasel’s daughter is the lead singer. Armando makes music videos for them, using Beardstown scenes as his backdrops.

[music]

Armando was born about 20 minutes from Beardstown, but his parents moved the family back to Mexico for work when he was 3 years old. In 2012, the family returned to Illinois when his father’s brother, a business owner, invited him to return. For a while, both of his parents worked at the meat-processing plant.

Over a long period, as Armando explained, his parents got their residency in the United States. And his mother is now a teacher here — as she had been in Mexico — and his father a warehouse worker.

[30:56]

TRUJILLO: I’ve also dabbled in writing. And I think it’s very easy for me to get in the head space of the setting, use this type of town as a setting. I find it very versatile. I’ve done a little bit of horror. I’ve done a little bit of … I’ve done a little bit of your fantasies, your other contemporary stuff. But I can get a lot of juice out of a setting like this. We’re right next to the river. You know, you got your patches of wood at around.

In fact, I don’t know if you guys have noticed, but we’re kind of in a bubble. Beardstown is kind of in the bubble. If you go in any direction, eventually you’re gonna go uphill. That’s because, like I said, we’re literally in a bubble. And that’s just kind of a very neat thing. And I’ve definitely been influenced by it in my work.

PIPA: As mentioned earlier, Buffy Tillitt-Pratt’s father was the mayor of Beardstown in the late 1960s when the town was courting Oscar Mayer. Her father actually flew to the company’s headquarters in Wisconsin and spoke face-to-face with Oscar J. Mayer himself to convince him to locate in Beardstown.

[32:10]

TILLITT-PRATT: There were three towns that were up to get the facility. He flew up there and had a meeting with him, and he said, face-to-face is the only way to deal with this. We want you to come to our community.

I think it one very important thing it taught me, when my dad wanted Oscar Meyer to locate here, we had people come to our house, Oh no, you can’t do it. So many people will move here from out of town, we’ll become like Detroit. It was the mindset, the mindset. It was, Oh, I’m afraid. I’m afraid we won’t be able to let our children play in the streets. There are going to be bad people come here. People have that mindset. There’s there’s no way you can teach them any different. All they can do is live through it and see it didn’t happen.

PIPA: As the people I talked to look towards the future for Beardstown, they love its small town feel and its multicultural vibrancy. They want to protect that.

TILLITT-PRATT: My friend, I don’t know if she’s standing around here, and she said she goes to our high school every day, our grade school every day, and she opens the door for the little children to come into the school, strictly volunteer. She says hello and she talks to them. She goes, when I was a little kid, I used to think when I got older I would travel the world, but I didn’t. Now I stay in Beardstown and the world comes to me. It’s true. It is true. They do come to her.

BRASEL: Well, I hope it can continue much as it is. I don’t want it to grow much more. I’m not a big fan of JBS, of course. But I love the diversity in town. I love the fact that you can see African women walking down the street with a jug of milk balanced on their head, and beautiful cultural displays of their own people’s own culture. You know, it’s just such a mix. There’s no neighborhood segregation. That’s what I love about Beardstown.

And I hope it stays like this. I would like it to stay just like this.

TRUJILLO: I want it to stay how it is in terms of its diversity. And I want that to mean an opportunity to grow for all of these various people to place their permanent mark, like stores, like businesses, that type of thing. If I grab a time machine and go into the future and see it turn into this huge city, that’d be a little horrifying. But I do want it to keep slowly growing. Maybe that’s the better thing for it. Have it slowly grow while maintaining its diversity and its uniqueness from all of the other towns nearby.

PIPA: Yet Beardstown residents recognize that they are directly affected by the uncertainty, the heightened passions, and the fear associated with immigration enforcement and policy changes being made at the federal level, and that it makes their everyday life, and the relationships that run through their small town, more complicated.

[35:24]

DELOCHE: My hope is that the rhetoric on both sides calms down to allow people to exist peacefully without having to wonder about what change is coming next. You were here for our Fall Festival; you saw a lot of faces of color downtown today. I would venture to say that the majority of the ones that you saw today were the people operating food stands. The majority did not come. The demographic in our square today was not what you would normally see on a Fall Festival weekend because of the current climate.

TILLITT-PRATT: I hope for more assimilation, which we are getting. Every four or five years it gets better and better. I hope for a, I’m trying to think of the word I want to say. I’m Republican, I’m conservative, but I’m hoping for a gentle approach to problems with immigrants. There are immigrants who have caused many problems. There are immigrants who are assimilating and helped save a little town the size of Beardstown from becoming a ghost town.

[music]

PIPA: It’s a stereotype of a small town that it takes forever for someone to earn the distinction of being “from there.” I’ve often had rural residents tell me something like “I’ve been here for 30 years, but everybody still considers me as someone who’s new to town.” But, frankly, one of the major themes that runs through this podcast is that even small changes in a rural community are often felt more acutely and more directly by its residents than in cities or suburbs.

Beardstown’s been experiencing significant change for decades now, and they’ve come to embrace it. They’re proud of their town and its diversity, and they delight in giving you recommendations for the best ethnic food in town. They’re proud to call the newcomers “neighbors,” and they recognize how important they’ve been to the vitality of the community. Yet it’s not been without tensions nor challenges. Building on what Buffy said earlier, they’re still “living through it.” But their story demonstrates that the local realities around immigration are far more complex than the national narrative that dominates our policy debates and our airwaves — and that’s a lesson we should all be grateful for.

Thanks for listening.

PIPA: My sincere thanks to all the people who shared their time with me for this episode.

[music]

To provide further policy insights based on this episode, we also publish a Q&A with an outside expert on the Brookings website. You can find the link in the show notes.

Many thanks to the team who makes this podcast possible, including Fred Dews, supervising producer; Molly Born, producer; Gastón Reboredo, audio engineer; Daniel Morales, video manager; Zoe Swarzenski, senior project manager at the Center for Sustainable Development at Brookings; Adam Aley and Elyse Painter, also in the Center for Sustainable Development, who provide research support and fact checking; and Junjie Ren, senior communications manager in the Global Economy and Development program at Brookings.

Also, my sincere thanks to our great promotions team in the Brookings Office of Communications and Global Economy and Development. Katie Merris designed the beautiful logo.

Finally, support for this podcast is provided by Ascendium Education Group. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication or podcast are solely those of its authors and speakers, and do not reflect the views or policies of the Institution, its management, its other scholars, or its funders. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence, and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment.

You can find episodes of Reimagine Rural wherever you like to get podcasts and learn more about the show on our website at Brookings dot edu slash Reimagine Rural. You’ll also find my work on rural policy on the Brookings website.

If you liked the show, please consider giving it a five-star rating on the platform where you listen.

I’m Tony Pipa, and this is Reimagine Rural.

More information:

- Listen to Reimagine Rural on Apple, Spotify, or wherever you like to get podcasts.

- Learn about other Brookings podcasts from the Brookings Podcast Network.

- Sign up for the podcasts newsletter for occasional updates on featured episodes and new shows.

- Send feedback email to [email protected].

- Find out more about the Brookings-AEI Commission on U.S. Rural Prosperity.

- Discover more research on Reimagining Rural Policy.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

PodcastHow immigration is reshaping and revitalizing rural Beardstown, Illinois

Listen on

Reimagine Rural

October 21, 2025