Persistent inequities by race and ethnicity in school discipline continue to circumscribe the educational experiences of students of color. Latino and Black students are more likely to face the harshest and most exclusionary forms of school discipline when compared to their white peers. These disparities begin when students enter school. In preschool, students of color are more likely to be suspended from school than children of other races and ethnicities, with Black students accounting for 43% of one or more preschool suspensions, despite only comprising 18.2% of U.S. preschoolers. Tragically, Black students continue to be suspended at a higher rate than their peers throughout their K-12 schooling experience. Disciplinary inequities are also concerning among Latino students, in particular Latino boys: One in five male Latino students is suspended before they enter high school.

These disparities raise profound questions about the historic treatment of Latino and Black children in U.S. public schools. In addition, they also raise concerns about the numerous, negative long-term outcomes that have been linked to harsh school discipline for these students, including lower academic achievement, a lower likelihood of civic engagement, and lower levels of educational attainment.

A variety of approaches have been taken to decrease the use of exclusionary school discipline for Black and Latino students. One such approach is to match students to teachers of the same ethnoracial group. A statewide analysis in North Carolina found that assignment to higher proportions of Black teachers decreased the likelihood of suspension for Black students. However, there has been less research on whether similar effects are present in large, diverse urban school districts, or, importantly, for Latino or Asian American students and teachers.

Findings from New York City public schools

To fill this research gap, our newly released study drew on 10 years of student and teacher data (2007-2017) from the country’s largest school system, New York City public schools.

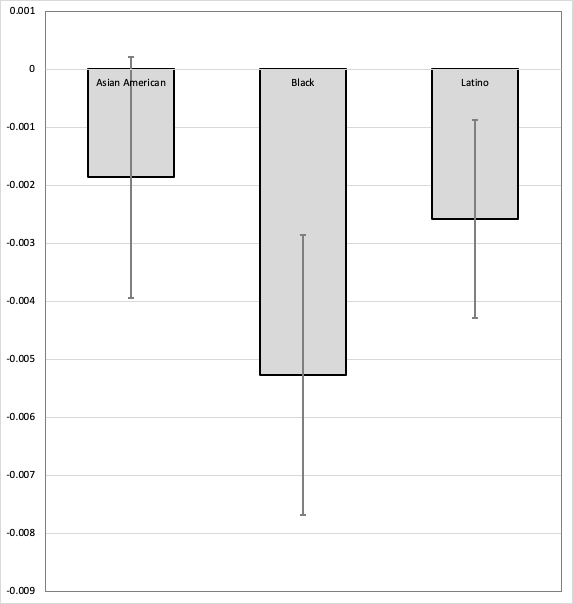

All three racial groups—Black, Latino, and Asian American—showed negative associations between exposure to same-race teachers and suspensions. In years that students in grades 4-8 were assigned more same-race teachers, they were less likely to be suspended from school, compared to years in which they were assigned fewer same-race teachers (see Figure 1). Black students showed the largest association, but the effects were statistically significant for Latino students, and of similar magnitude (although only marginally significant) for Asian American students. This is important, as prior studies have found this relationship among Black students only, but our work suggests this race-match benefit is not unique to Black students.

Figure 1: Estimated effects of ethnoracial student-teacher matching on the likelihood of suspension for Asian American, Black, and Latino students in grades 4-8, New York City, 2007-08 to 2016-17

So how big of a difference does this make to students? As a hypothetical exercise, we estimated the change in student discipline if we were to increase student exposure to same-race teachers among each group by one standard deviation. Clearly, there are a variety of practical obstacles to changing the composition of the teacher workforce so drastically, and it would be impossible to raise the exposure of all students to ethnoracially matched teachers at once without increasing racial segregation among students, which is certainly not desirable. Still, this thought exercise allows us to imagine the potential magnitude of the impacts of teacher diversity efforts on student discipline.

Table 1 shows the results of this thought experiment. As the table shows, our estimates suggest that if we raised the representation of Asian American, Black, and Latino educators that teach same-race students in grades 4-8 in New York City by a standard deviation, we might expect the suspension rates for those students to drop by approximately 3%. Although this is a small decline in percentage terms, given the sheer numbers of students in New York City, we estimate that, over the 10 years we study, such a decline would translate to roughly 230 fewer instances of suspension for Asian American students, 1,800 fewer suspensions for Black students, and 1,600 fewer suspensions for Latino students over that period. Given the median length of suspension— five days for Black and Latino students, three days for Asian American students—this translates to approximately 680 more days in school for Asian students in grades 4-8, 9,000 additional days in school for Black students, and 8,000 additional days in school for Latino students over the 10-year period.

Table 1: Observed and estimated numbers of suspensions and days of suspension for Asian American, Black, and Latino Students in grades 4-8, New York City, 2007-08 through 2016-17

| Asian American | Black | Latino | |

| What we observe | |||

| Mean proportion same-race teachers (SD) | 0.09 (0.21) | 0.40 (0.40) | 0.20 (0.31) |

| Suspension likelihood | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Median suspension length (days) | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| # student-year observations | 589,403 | 919,139 | 1,428,737 |

| Thought exercise: Raise mean proportion same-race teachers by 1 SD | |||

| Estimated % change in suspension likelihood | -3% | -3% | -3% |

| Estimated change in # suspensions | -227 | -1,789 | -1,561 |

| Estimated change in total days of suspension | -680 | -8,945 | -7,803 |

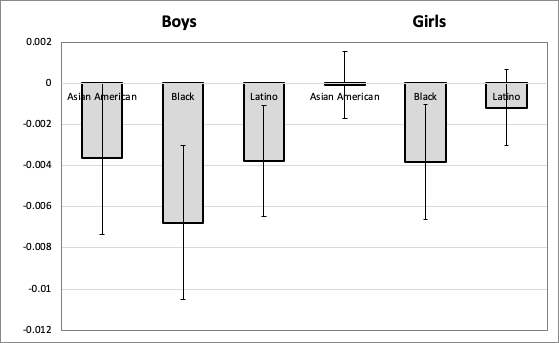

Interestingly, the magnitudes of our estimates differed by gender for some ethnoracial groups but not for others. Our estimates of the effects of assignment to ethnoracially matched teachers were statistically significant for Black boys and girls, and roughly similar in magnitude, although the estimates for Black boys were slightly larger (see Figure 2). For Latino and Asian American students, however, we found larger impacts for boys, and smaller, statistically insignificant effects for girls.

Figure 2: Estimated effects of ethnoracial student-teacher matching on the likelihood of suspension for Asian American, Black, and Latino students in Grades 4-8, separated by gender, New York City, 2007-08 to 2016-17

Overall, our findings suggest that student-teacher ethnoracial matching has significant but modestly sized impacts on exclusionary school discipline for Black and Latino students, and similarly sized (although marginally significant) impacts for Asian American students. These findings add to the broad body of evidence suggesting that ethnoracial matching between students and teachers has a variety of benefits for students of color, including on academic performance, high school graduation, college-going, and other important outcomes. Our research illustrates another potential benefit of a more diverse teacher workforce that more closely reflects the backgrounds of students.

Recommendations for Practitioners and Leaders

So, what’s to be done in the areas of research, practice, and policy to decrease the rate of exclusionary discipline in school districts, such as New York, in which students of color are disproportionately suspended compared to their white peers?

First, the research community must continue to document the practices, approaches, and/or beliefs that teachers of color employ that influence the decreased use of exclusionary discipline for students of color. Beyond documenting that having more ethnoracially matched teachers causes a reduction in the likelihood of suspension, we must also examine the mechanisms in classrooms that lead to this outcome. When compared to their colleagues, how are Latino teachers organizing their classrooms in ways that lead to lower rates of suspension for their Latino students? How are Black teachers designing and enacting practices that cause their Black students to be suspended less than if those students were taught by a white teacher? Answering these critical questions will provide the field of educational research with a greater understanding of what and how such practices, approaches, and beliefs used by teachers of color make them less likely to suspend their students of color. In turn, teacher training and professional development can focus on developing those practices, approaches, and beliefs in all teachers.

Second, and relatedly, urban school districts should focus specific efforts on (re)designing induction and ongoing professional learning for white teachers regarding discipline practices for students of color. The design of this professional learning should consider the ongoing research called for above, and be informed by our learning about the practices, approaches, and beliefs that shape the discipline work of teachers of color with students of color. In addition, districts should also create opportunities to develop and sustain the capacity of white teachers to understand and explore how their implicit biases might contribute to the disproportionate rate at which they discipline Asian American, Black, and Latino students.

Third, policymakers in large, urban school districts should maintain and augment their teacher diversity recruitment and retention efforts. While New York, along with many large, urban districts, has made some initial investments to increase the ethnoracial diversity of its educator workforce, our work demonstrates that such efforts can reduce the use of exclusionary discipline for these students. Our findings also suggest that such efforts, which have largely focused on Black and Latino teachers to date, could be expanded to Asian American teachers. Recent increases in anti-Asian-American hate attacks in New York and elsewhere suggest that New York and other large, urban districts should make hiring and retaining Asian American teachers an additional focus of their teacher diversity efforts, as these students also stand to benefit from a teacher workforce that more closely reflects the diversity of its students.

Closing ethnoracial disparities in the use of exclusionary discipline in schools will require a variety of efforts at the teacher, school, district, and state levels. In New York, for example, a variety of efforts have focused on addressing the disproportionate application of exclusionary discipline to students of color, including The Racial Literacy Project at Columbia University. Our research shows that efforts to diversify the teacher workforce, learn from the discipline practices of teachers of color, and train teachers on the unconscious biases that may shape disciplinary practices in schools should be a continued part of these efforts.

Acknowledgements: This research was supported by funding from the Walton Family Foundation, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, and the William T. Grant Foundation. We thank the New York City Department of Education for providing access to the data and Richard Haynes and Melissa DeFeo for their assistance. We also thank Rebecca Proctor for her valuable research assistance.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).