Across the U.S., education leaders grapple with emerging questions about the best approach to student discipline. These questions stem from heightened concerns that disciplinary tools that remove students from school, such as out-of-school suspensions (OSS) and expulsions, may harm the removed students’ future educational achievement and attainment. This is particularly worrisome considering that suspensions are not evenly distributed across students. For example, Black students in secondary schools miss over five times more days of school due to suspension than do their white peers.

Practically, however, doing away with suspensions altogether presents challenges. Even if a suspension harms the individual student removed from school, the school might benefit more generally in terms of enhanced school safety or reduced distractions within the learning environment. Further, harsher disciplinary practices could theoretically deter other students in the school from future misbehavior. Indeed, some educators report increased difficulties in maintaining orderly learning environments without the option of removing disruptive students from the classroom. They also report feeling unsafe themselves. Without sufficient evidence on the relative magnitude of both direct and indirect impacts of disciplinary practices on students, school leaders are left in the lurch.

New evidence comparing the effects of more and less punitive principals

In a recent study co-authored with Shawn Bushway and Elizabeth Gifford, we look at the role of principals in driving school disciplinary practices, and the role of principal disciplinary decisions in shaping long-term student outcomes. To do so, we link nine years of data on student disciplinary referrals to education records, juvenile justice records, and adult conviction records in North Carolina. Our method relies on a comparison of different principals working in the same school at different points in time. Even within the same school, and even for the same type of student offense, two principals may vary widely in the likelihood of assigning a suspension—perhaps reflecting different attitudes toward use of this punishment. Based on our data, this is indeed the case. For the average type of middle school disciplinary offense, some principals almost never assign an out-of-school suspension; others do so the majority of the time.

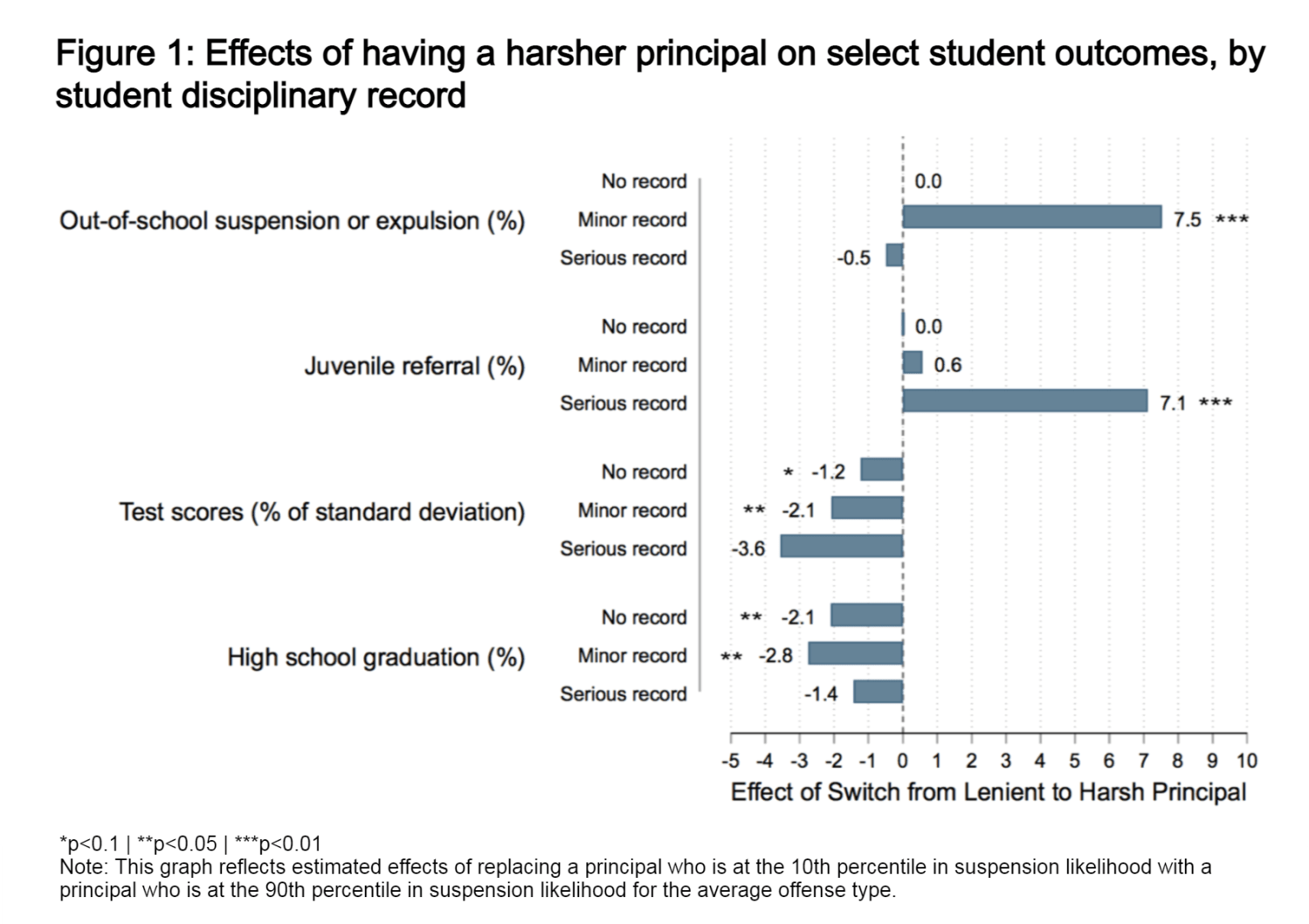

These decisions made under the discretion of principals, or their administrative teams, have consequences. By definition, replacing a more lenient principal (10th percentile likelihood to suspend) with a harsher principal (90th percentile likelihood to suspend) increases the rate of OSS and expulsion. It does so particularly for students who commit minor offenses, such as disrespectful behavior, inappropriate language, or showing up late to class. For students who commit more serious offenses, having a harsh principal also increases the likelihood of a juvenile justice referral.

Stricter disciplinary practices do yield a small deterrent effect, decreasing minor student misconduct by 9%, but have no effect on the incidence of serious crime. Further, there were no positive spillover effects of disciplinary severity on the learning of students who did not get suspended. If anything, these non-suspended students had slightly lower test scores and high school graduation likelihood under harsher principals.

Figure 1 shows the estimated effects of replacing a principal at the 10th percentile in suspension likelihood with one at the 90th percentile. It disaggregates the effects on students with no discipline record, a minor record, and a serious record. It shows, for example, that students with no discipline record are 2.1% less likely to graduate high school with a harsh principal than they would be with a lenient principal.

Stricter principal disciplinary approaches have especially disruptive impacts on students who commit minor offenses. Students who are reported for such minor misconduct under a harsher principal, as compared with those reported under a more lenient principal, ultimately show:

- Higher likelihood of OSS or expulsion

- More absences from school

- Lower math and reading test scores

- Higher likelihood of grade retention

- Lower likelihood of high school graduation.

We can think of this group of students as adolescents on the margin between positive engagement in school and disengagement from school. Under a harsh principal, student acts of minor misconduct turn into suspensions, which further detach the student from school. Under a more lenient principal, the student misconduct is dealt with in a less exclusionary manner, and students fare much better academically.

Uncovering racial bias in disciplinary decisions

Our study also finds that, on average, principals are more likely to assign OSS or expulsion to a Black student than to a white student, holding constant both the severity of the disciplinary offense and the student’s prior disciplinary history. However, the amount of racial bias exhibited in disciplinary decisions varies widely across principals. Principals who are more racially biased in their disciplinary decisions lead to improved educational outcomes for white students but worse outcomes for Black and Hispanic students. Either the suspending behavior of principals itself has disparate effects on different groups of students, or principals who exhibit racial bias in their disciplinary decisions also tend to act in other ways that foster racial inequality in the school environment.

What does this mean for school discipline reform?

The finding that suspensions can have negative effects on students is not new. Many schools and districts across the country have begun a shift toward replacing exclusionary discipline with more proactive approaches, such as restorative justice and positive behavioral interventions—with promising (albeit somewhat inconsistent) results.

Within this policy shift, our study emphasizes the unique importance of school leadership in driving disciplinary practices and culture. Any efforts to mitigate inequities in school disciplinary policies and systems will need to seriously consider the amount of discretion afforded school principals in assigning disciplinary consequences. For principals facing these difficult decisions about student punishment in their day-to-day work, the evidence from our research recommends erring on the side of leniency.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).