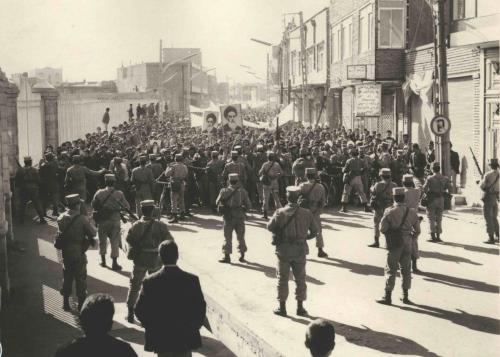

The Soviet leadership was surprised by the Iranian revolution to an even greater degree than the Carter administration in the United States, even if the interests of the USSR were less directly affected. There was no shortage of information, but the problem was that the spectacular collapse of the shah’s state contradicted the three main Soviet perspectives on developments within Iran. The first one portrayed Pahlavi’s regime as the main regional ally of the United States and assessed Iran’s military capabilities as superior to any external and domestic challenges. The second perspective focused on the leftist opposition—primarily the Tudeh (or masses) party—and exaggerated the strength of shah’s intelligence service, SAVAK. The third perspective depicted the Islamic movement as archaic and dismissed Ayatollah Khomeini as a marginal figure. None of these readings of the Iranian revolution produced a useful interpretation of the events, and the misinformed recommendations resulted in a chain of blunders that contributed to the collapse of the USSR just 12 years after the Iranian metamorphosis.

The misconceptions were developed by three different bureaucracies: first by the military intelligence (GRU) and further by the General Staff; second by the KGB; and third by the international department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party. The interplay between these institutions and their perspectives was distorted by the political crisis in Afghanistan, which had an entirely different character than the Iranian turmoil, but occurred simultaneously—and from the Moscow’s view on the world, threatened the same southern periphery of the USSR.

The time of troubles in Afghanistan started in April 1978, when a group of “progressive” officers organized a coup against President Mohammed Daoud Khan and murdered most of his family. Moscow had maintained close ties with Daoud Khan’s regime and didn’t instigate the coup, but had to accept a fait accompli—and justified it as the “April revolution.” Soviet relations with the government of Nur Muhammad Taraki were further upgraded, and that turn of events reinforced the perception of the army as the dominant political force (with a propensity to internalize Communist ideas) in the wider Middle East.

The failure of shah’s army and the SAVAK to suppress the unrest stunned the Soviet authorities, and before a coherent interpretation was developed, the situation in Afghanistan spun out of control. On September 14, 1979, soon after returning from a trip to Moscow, Taraki was assassinated by his rival Hafizullah Amin, who sought to establish an even more brutally dictatorial regime. Decisionmaking in the Kremlin on restoring order in Kabul, which had come to be seen as an important ally, was agonizingly incoherent, but one of the key considerations was the assumption that U.S. attention was preoccupied with the hostage crisis in Tehran, dragging on beginning November 4, 1979. There were also persistent—and entirely misplaced—concerns in Moscow that Washington would organize another coup in Iran, perhaps in combination with a military intervention.

The very narrow circle of elderly decisionmakers in the Politburo had reason to believe that the Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan, described as “brotherly help” and the performance of “international duty,” would be criticized but effectively accepted by the United States and Western Europe because of their deepening worries about the violent mess in Iran. They certainly got it wrong and were astounded not only by the ostracism in the West, but also by the fierce condemnation from revolutionary Iran, where the USSR was defined as the “Lesser Satan.” A stronger distraction from the gradually escalating hostilities in Afghanistan was needed, and the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War in September 1980 provided just that. Moscow declared “neutrality” in that war, but served as the main supplier of arms to Iraq in hopes of mollifying key Arab states, which had been alienated by the invasion into Afghanistan. It is obvious in retrospect that the strategy of covering one mistake with another blunder was doomed to be a mega-failure, and in this fashion, the debacle in Afghanistan became a major driver of the collapse of the “indestructible” Soviet Union.

The very narrow circle of elderly decisionmakers in the Politburo had reason to believe that the Soviet military intervention in Afghanistan, described as “brotherly help” and the performance of “international duty,” would be criticized but effectively accepted by the United States and Western Europe because of their deepening worries about the violent mess in Iran. They certainly got it wrong and were astounded not only by the ostracism in the West, but also by the fierce condemnation from revolutionary Iran, where the USSR was defined as the “Lesser Satan.” A stronger distraction from the gradually escalating hostilities in Afghanistan was needed, and the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War in September 1980 provided just that. Moscow declared “neutrality” in that war, but served as the main supplier of arms to Iraq in hopes of mollifying key Arab states, which had been alienated by the invasion into Afghanistan. It is obvious in retrospect that the strategy of covering one mistake with another blunder was doomed to be a mega-failure, and in this fashion, the debacle in Afghanistan became a major driver of the collapse of the “indestructible” Soviet Union.

It is obvious in retrospect that the strategy of covering one mistake with another blunder was doomed to be a mega-failure.

The geopolitical gain for the USSR from the breakdown of the alliance between Iran and the United States was negated by the severe deterioration of its position caused by the mismanaged Afghan war. For Moscow, the security threat from the “old” Iran was familiar and manageable, but the new challenges from Islamic fundamentalism and insurgency were incomprehensible and insuppressible. Soviet military command had to concentrate far greater effort on waging this peripheral war than it wanted. As far as Iran was concerned, Soviet top brass were shocked by the collapse of shah’s army, but found the capacity of the chaos-consumed Iran to regroup and repel Iraq’s aggression astounding. For the KGB, the post-revolutionary extermination of the Tudeh party and other prospective Soviet allies within Iran was shocking and the spread of the Islamic networks and influence appeared deeply disturbing. The Politburo elders and the dogmatic party-ideological apparatus were unable to comprehend the sustained public mobilization in Iran for the Islamic cause and to explain away the rising resistance in Afghanistan.

The Soviet Union, as it happened, had no long-term perspective, and Russia has successfully made peace and even entered into an alliance of sorts with Iran’s Islamic Republic, which is no longer its neighbor. This rapprochement has brought Russia much trouble, as it is increasingly obvious in Syria. However, it has not erased the fundamental incompatibility between Russian opportunistic policy of asserting its “great power” status and Iranian ideological policy of advancing the cause of the still-spirited Islamic Revolution.

Commentary

How bad judgement calls brought a chain of blunders: Soviet responses to the Iranian revolution

March 7, 2019