How can the world forge the cooperation needed to manage climate change? Most answers to that question hinge on the challenge of enforcement. It is easy to dream up bold agreements but hard to make them stick.

Over the last decade, there has been a lot of new thinking about how international treaties on climate change, the main mechanisms for cooperation, can be made more effective. Gone is the idea that global treaties reached through consensus, such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), can, by themselves, force governments to take actions and marshal penalties on those that drag their feet. Instead, this new theory emphasizes how small groups of highly motivated governments and firms invest in new technologies and business models. In effect, they run experiments and learn quickly which work and which fail. Those experiments, in turn, lay the tracks for new industrial futures and make it costly for other firms and governments to drag their feet.

But what motivates these leading firms and governments to act? Nearly every answer turns, at least in part, to public opinion and thus to the media as the main conduit for shaping public information. Absent focused public pressure, it would be easy for governments and firms to hide and prevaricate. Anecdotal evidence of media attention focusing public pressure abounds — for example, recent exposés (see here and here) about how carbon offsets aren’t working have led many firms and agencies to adjust their strategies. In turn, that is shaping how the leaders that are the engines of international cooperation make investments.

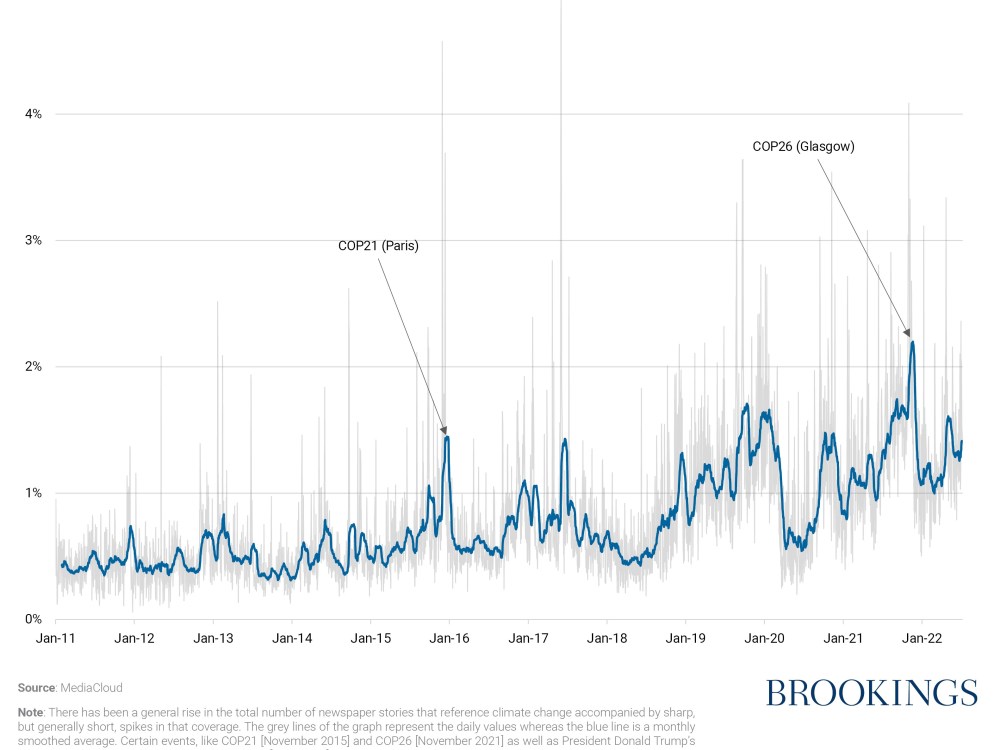

Anecdotes are helpful, but it’s possible to do better. To take the systematic pulse of media coverage, we focus on the annual event that reliably captures the most attention to climate change: the Conference of the Parties (COP) of the UNFCCC. The 27th iteration of the conference, held in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, recently concluded this November. For the most part, it was a disaster. But it could have been worse, and all the talk of disappointment has clouded the bigger, more important, and more hopeful story: The public is paying a lot more attention to climate cooperation these days.

Many earlier studies (like here and here) have looked at elite media, such as newspapers of record. That approach is good at reflecting what elites think, but it is prone to bias — especially as more of those papers invest in their climate desks by hiring more reporters and generating, autonomously, more reporting. Focusing on what elites, who pay attention to U.N. conferences, think is a misleading way to measure political interests, especially in countries where political systems become polarized against those elites.

Here we take a different approach, made possible by new data sources that allow a systematic look at a broader swath of media coverage. We focus on the United States and use the database of Media Cloud, a research consortium, to analyze over 11 million news stories from over 10,000 separate U.S. news outlets from 2011 to 2022. It includes elite papers like The New York Times or Wall Street Journal, but most of the database contains the content of more lilliputian and local purveyors of news. (The stories include syndication, and future research might probe, if possible, whether local news outlets are primarily conduits for nationally-curated stories or suppliers of new content. We suspect the conduit role is an important one.)

According to this broader look at American media, as shown in figure 1, coverage has gone up, and much of that coverage is tightly timed with the COPs. We measure coverage by looking at the percentage of all articles that address climate, and wonks will find more fodder in the caption. Two COPs have attracted the most attention — COP21 (2015) in Paris, which produced the landmark Paris Agreement, and COP26 (2021) in Glasgow, which was the first significant update since Paris. These attracted attention because the hosts organized them as major events, and the diplomats delivered. Other trends are also clear, such as a plummet in coverage as other topics rose quickly to capture public attention, such as in early 2020 (the global pandemic) and early 2022 (Russia’s invasion of Ukraine). A big rise starting in the fall of 2019 (until the pandemic plunge) is linked to the substantial climate protests which started in September and focused on the U.N. General Assembly meetings that month. (The world is complex, of course; in our assessment, we take a cue from Max Boykoff and his colleagues.)

This rising volume of coverage is important because it’s a sign that the public, increasingly, is paying attention to the marquis moments for international cooperation on climate change. Indeed, there’s a significant body of research that demonstrates the link between the volume of media coverage and the perceived legitimacy and urgency of an event. Examples of this linkage exist in as varied topics as Initial Public Offerings, social protests, and the European refugee crisis. In the field of climate change, specifically, intensified media coverage in general, of protests, and of international conferences is directly linked to heightened public concern for and elevated attention to the issue. In addition, an increased volume of climate-related coverage is linked to support for public policies to address climate change.

All this is encouraging because it also suggests that the enforcement mechanism available to the COP system — public attention — may be working. The public is focused on climate change, increasingly, and many of the spikes in attention are linked to the premier annual global event aimed at boosting cooperation.

Because figure 1 looks at all coverage related to climate change at any time of the year, in figure 2 we look at just the peak coverage of climate change during the period of time when a COP is underway. Here the variation, and trend, in COP performance is striking — with Paris in the clear lead. Every COP since Paris (except one, Bonn in 2017, which dealt almost exclusively with dreary procedural matters) has attracted more coverage than before Paris.

Anecdotally, at least, it seems clear that there is a sharp linkage between the expectations and successes of COP and media attention. Paris and Glasgow were media blockbusters and expected to achieve a lot. By contrast, little was expected to materialize from the negotiations that took place in Egypt during COP27 this year, which notably avoided complete failure by reaching an agreement in the final hours on a “loss and damage fund,” but that victory was far more prosaic than profound since the fund remains empty and there’s little agreement on what it should do.

What’s also interesting is the daily cadence of media coverage as each COP unfolds — day by day (figure 3). The most successful COPs peak on day 1 — merely holding the event, after months of buildup and expectation, is the event. This insight might offer useful guidance to governments who want to host future COPs and are keen for them to play a bigger role in attracting public attention. It is vitally important for each COP to have a purpose. Also crucial is to curate the media engine that pushes public attention — something that the French and British hosts of the two leading COPs did with aplomb. Combining purpose and curation is a months-long activity that generates rewards the moment the COP curtain rises.

Of course, national political debates about climate change are about a whole lot more than just public attention to COPs. In the United States, a central issue is political polarization, and advocates for climate policy need to pay much closer attention to how they communicate information about climate change to different audiences. That’s a big topic and one pockmarked with challenges of linking causes and effects. In figure 4 we show one snapshot: the roughly one-third of news stories about climate change that are published by polarizing news outlets. (Wonks, again, find solace in the caption.)

Both sides of the American political divide are paying attention to climate change at about the same levels, except in 2018 and 2019 when liberals were much more glued to the perils of global warming. Looking deeper into the data, what’s clear is that liberal media sources give about 30% to 40% more attention to the physical harms of climate change. Liberals talk a lot about gloom and doom; conservatives don’t. Whether gloom and doom actually convince the unconvinced to act is another matter, although some studies suggest it’s a bad political strategy, at least when not paired with examples of action.

On average, liberals also pay more attention to COPs. During an average year, left-leaning outlets increased their coverage of climate change by 23% during the two weeks of a COP. Right-leaning outlets saw only a 15% increase.

Looking more closely at media coverage offers the hope of linking new theories of change about international cooperation to the broader public that puts pressure on firms and governments to cooperate. But there’s a lot more research needed that looks at cause and effect and more closely at the content of media coverage and messages. Counting articles, of course, is no substitute for reading them — a task eased with text analysis, which now is readily automated and can be used to assess the content and tone of the media coverage. There’s a role for experiments and learning what works, as well. For instance, a recent study ran survey experiments to identify what types of messaging impacted support for climate-related policies. By pulsing a large sample of voters with different bits of information, they found that emphasizing a policy’s impacts on inequality, emissions, and the survey respondent’s own household sharply affected the respondent’s support for the policy.

A lot is expected from the yearly COPs. For the next one — COP28, in the United Arab Emirates — the organizers are just gearing up and already face many challenges in attracting global public attention. So far, there’s little that’s concrete on the agenda and many other topics in global politics and economics are consuming public attention. But the runup to COP28 is early and the Emirati hosts have a lot they could showcase. With the right nurturing, the global public might also pay close attention to the “stocktake” efforts underway under the Paris Agreement — a major effort to assess how well the Paris process is working.

The Emirati hosts will need a dedicated effort to drive media attention and public interest. One way to do that is to develop messages that resonate with the COP event — in this case, with how an event focused on climate change can benefit from more engagement from the oil and gas industry that has long dominated the country. Finding ways to link conventional fossil fuels to serious action on climate change has long been elusive, but maybe that’s one way that the UAE can combine its strengths as a country with the public’s desire for messages on climate change that resonate.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Good news about global warming: The public’s paying attention

February 10, 2023