The eighth Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) ministerial meeting that took place in Dakar, Senegal, concluded just last week. Like previous FOCAC meetings, China presented its vision for China-Africa relations for the next three years, this time under the theme “Deepen China-Africa Partnership and Promote Sustainable Development to Build a China-Africa Community with a Shared Future in the New Era.” A review of the content, however, illustrates significant shifts in China’s priorities, emphasis, and approaches from its earlier patterns. In fact, the Financial Times has lamented the quantitative reduction of China’s financial commitments from $60 billion in 2018 to $40 billion this year. However, it is the qualitative changes that raise bigger questions as to whether China is leaving Africa after two decades of robust and ever-growing engagement. Some of the shifts could be temporary and tactical. However, the impact of the others could be far-reaching and long-term.

A downgrade of the FOCAC meeting?

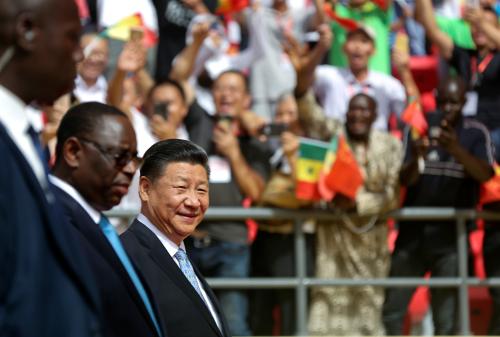

Unlike the past two FOCAC meetings—Johannesburg in 2015 and Beijing in 2018—that, respectively, garnered 13 and over 50 African heads of state or government, the Dakar FOCAC meeting this year was a ministerial-level meeting. Chinese President Xi Jinping delivered a speech virtually, which did boost the seniority level of the meeting, but such a change in attendance raises the question as to whether FOCAC has been downgraded.

The answer is negative. Since its inception in 2000, FOCAC was a ministerial-level event that alternates between Beijing and Africa every three years. The Chinese president has always attended the meetings in Beijing, but, before Xi, the premier attended FOCAC meetings in Africa (Ethiopia in 2003 and Egypt in 2009). It is under Xi that the two FOCAC meetings in 2015 and 2018 were upgraded to leadership summits. This most recent change creates the impression of the Dakar meeting being at a lower level. Though, admittedly, the COVID restrictions likely also played a role.

Scaling back activities

The most significant changes for FOCAC happened quantitatively and qualitatively. Quantity-wise, China is significantly scaling back its planned activities in Africa. For agricultural assistance, climate and environment, health, peace and security, and trade promotion, the number of committed projects for each category dropped from 50 projects in 2018 to 10 projects this year. For capacity building, the educational and training opportunities offered decreased from 50,000 government scholarships and 50,000 training opportunities three years ago to 10,000 training and seminar opportunities for high-end talents this time. These are drops of 80 and 90 percent, respectively.

Substance-wise, the content of each category also shrank. For example, under climate and environment, the 2018 commitment included items from maritime cooperation to wildlife protection, from policy dialogues to joint studies to professional training. However, this year, only two items were included: the “Africa Green Great Wall” and demo centers for low-carbon and climate change adaptation. The scope of public health support also was scaled back from a long list in 2018 covering the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC), disease control cooperation, information sharing, friendship hospitals, training of African doctors and medical teams, traveling clinics, and special projects for women and children, to a very brief action item of “dispatching 1500 medical staff and public health experts” this year. The rest of the actions are all related to COVID-19. Similar cutbacks are equally evident in the people-to-people exchanges and peace and security categories.

Shifting away from infrastructure

Perhaps the most striking element of China’s FOCAC commitment this year is the complete disappearance of infrastructure from the narrative. Indeed, throughout Xi’s keynote speech, the word “infrastructure” did not appear even once—a sharp contrast to the four direct references to infrastructure in his 2018 keynote. In China’s 2018 FOCAC commitment, connectivity infrastructure was listed as the No. 2 priority among the eight action plans, focused mostly on hard infrastructure projects on the ground.

Given China’s long history of infrastructure development in Africa, the omission of infrastructure in China’s new commitment is simply glaring. Despite China’s claim of altruistic intent, many of the projects are controversial. Especially with the debt sustainability issues since the COVID-19 crisis, Chinese loans used for such infrastructure development have put several governments in difficult spots, such as the potential Chinese takeover of Uganda’s Entebbe airport, the potential seizure of Kenya’s Mombasa port, and the recurring debt repayment issues Zambia struggles with. These controversies loomed large in the background of the FOCAC meeting this year.

The lack of reference to infrastructure in China’s FOCAC commitment does not suggest that China will exit the domain. After all, China has accumulated a large number of ongoing infrastructure projects with loan terms, especially after their debt renegotiation, extending far into the future. In addition, Chinese contractors still enjoy unique strengths on the market, such as in cost control and efficiency, which enable them to continue to play their role in the future of the African infrastructure development market. However, this shift away from infrastructure development in Africa, if sustained, could be the most significant change in China’s engagement with Africa in recent years.

Ensuing change in financing

One of the primary drivers of Chinese lending, especially in terms of loans and export credit (totaling $35 billion in the 2018 package) was to support this infrastructure development. Such lending has consistently facilitated the procurement of Chinese services and products. However, as China shifts away from infrastructure, the pattern of Chinese financing is bound to change.

The change is well-reflected in the $40 billion China committed in Dakar. China will continue to push Chinese companies to invest a much smaller $10 billion in Africa in the next three years—at the same level as in the 2018 commitment. The big change came in credit: Not only will China provide only half the previous amount, dropping from $20 billion to $10 billion, but it also will provide the credit only to African financial institutions for them to support the development of African companies. In the past, this line item was provided to African governments to fund Chinese projects. The introduction of African financial institutions as the middleman will free China from the decisionmaking, hence shielding it from being the direct culprit of the debt stress Africa has run into.

China is also allocating $10 billion from its share ($29.216 billion) of the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) new allocation of $650 billion special drawing rights (SDR) to Africa. China is not unique in this respect: This transfer is in line with the IMF’s call for wealthy countries to channel their share to less-developed countries. For example, France has announced that it intends to transfer 20 percent of its new SDRs to African countries. Notably, the U.K. has advocated for the same, but is using its new SDRs as a device to cut its traditional foreign aid while appearing to maintain its commitment to foreign aid. China appears to share the U.K.’s aspiration: to maintain its financial commitment to Africa while reducing the cash it must spend directly from its pocket.

The one growing category in China’s financial commitment to Africa is trade finance, and the country correspondingly doubled its 2018 commitment of $5 billion. The funding will support African products and service exports, with the aim of enhancing their value added. The increase is due to the better-than-expected result of the trade funding in the past three years. Under the China Exim Bank, the amount distributed exceeded the original commitment and reached $6.2 billion due to popular demand.

Increased focus on trade facilitation

The fact that trade finance was the only growth point of China’s financial commitment to Africa suggests one thing: that China eyes growing trade with Africa as its priority. According to Xi’s statement, China aims to increase its imports from Africa to a total of $300 billion in the next three years. China’s imports from Africa in 2020 were $72.7 billion. At this rate, such imports will have to expand by 27.3 percent to hit the target, which is a fairly ambitious number.

The priority in promoting African exports to China is partially motivated by the Chinese desire to balance trade with Africa, as Beijing is sensitive about the large trade deficit Africa runs. At the pre-FOCAC press conference, the Chinese Ministry of Commerce went as far as to portray China-Africa trade as “mostly balanced” in the past two decades, with $1.2 trillion in imports from Africa and $1.27 trillion in exports to Africa. However, this numbers game conveniently disguises a large and growing trade imbalance. In 2019, China’s trade surplus against Africa was $17.7 billion ($113.2 billion in Chinese exports and $95.5 billion in Chinese imports). In 2020, the imbalance grew 243 percent, to an astounding $41.5 billion, with $114.2 billion in Chinese exports and $72.7 billion in Chinese imports.

The worry about the trade imbalance and its optics are why trade promotion occupied a high priority in China’s action plans for the next three years. And Beijing appears ready to beef up the efforts with faster inspection and quarantine procedures, more products under zero-tariff, etc.

Conclusion

Observers have called China’s FOCAC commitment from the Dakar Meeting “underwhelming.” Indeed, with the vivid memories of the recent extravagant packages from 2015 and 2018, the Dakar meeting suggests a Chinese retrenchment from FOCAC—and from Africa. The amount of financial commitment, the number of promised projects and opportunities, and the relatively thin content of the action items together illustrate China’s cutback of activities on the African continent.

The cutback is in line with the shifting priorities and approaches of China in Africa. Beijing is visibly moving away from its infrastructure-centric and Chinese loan-heavy approach of recent years. The new focus, however, is less evident. Trade promotion, especially facilitation of African exports to China, appears to be the key. But it is hard to imagine that trade could fill the large space infrastructure development has occupied in China-Africa relations in any meaningful way.

The origin for this shift is multifaceted. Chinese loans to Africa have run into viability challenges and suffer from the social stigma as “debt traps.” Given all the loan repayment problems that have occurred so far, it is conceivable that both China and Africa would want to slow it down on this particular front. China’s own economic slowdown is another factor. No one expected China’s financial commitment to Africa to grow indefinitely. However, the impact of COVID-19 and travel restrictions on the Chinese economy, as well as the impact of the trade war, are all taking a heavy toll on China’s financial capability to sustain the spending the world witnessed in the earlier years.

While the shift is real, it remains to be seen as for whether it is a short-term tactical change or a long-term strategic reorientation. After all, COVID-19 is a black swan event that has deeply affected the modality of China-Africa relations, and the world is still gauging its impact and time horizon. Until those questions are answered, it is hard to predict which way the African economy will turn. So, there is no guarantee that China-Africa economic ties will not resume some of their old patterns in the future. However, at least for the time being, adjustments are well under way, and the Dakar FOCAC meeting is the most powerful and authoritative illustration of it.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

FOCAC 2021: China’s retrenchment from Africa?

December 6, 2021