This paper is part of the fall 2020 edition of the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, the leading conference series and journal in economics for timely, cutting-edge research about real-world policy issues. Research findings are presented in a clear and accessible style to maximize their impact on economic understanding and policymaking. The editors are Brookings Nonresident Senior Fellow and Northwestern University Professor of Economics Janice Eberly and Brookings Nonresident Senior Fellow and Harvard University Professor of Economics James Stock. Read summaries of all the papers from the journal here.

Click here to download the data and programs for this paper.

The federal deficit temporarily ballooned in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, but remarkably low interest rates, expected to continue for much of the coming decade, mean the long-term budget outlook is only moderately worse now, finds a paper that was discussed at the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (BPEA) conference on September 24.

“Because low interest rates create ‘breathing room’ for fiscal policy, we do not see the large short-run debt accumulation … as necessitating any immediate offsetting response,” write Alan J. Auerbach of the University of California-Berkeley, William Gale and Louise Sheiner of the Brookings Institution, and Byron Lutz of the Federal Reserve Board. However, they warn, “long-term projections show that significant fiscal imbalances remain and will eventually require attention.”

Meanwhile, state and local governments, which generally must balance their budgets, entered the pandemic in a relatively strong position, with $119 billion in rainy day funds and general budget surpluses. Nevertheless, they will require additional federal assistance to avoid cutting necessary services in the years ahead, the authors write in Fiscal effects of COVID-19.

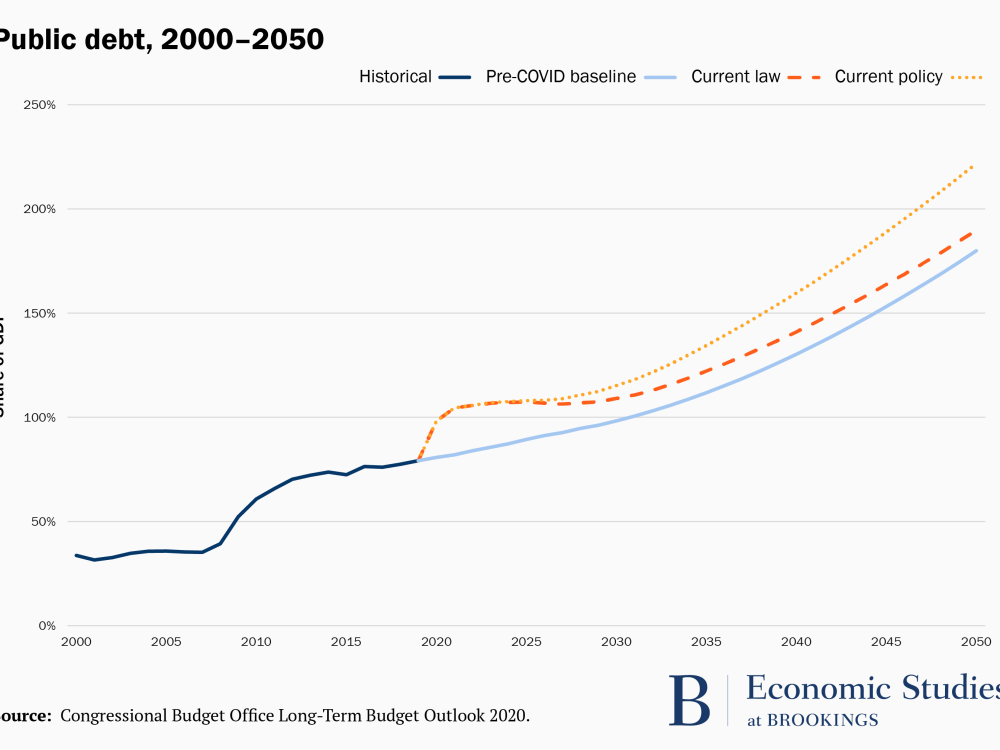

Federal borrowing surged between April and June, and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects, based on the continuation of current law, that the ratio of accumulated federal debt to gross domestic product (GDP) will jump from 79 percent in fiscal year 2019 to 98 percent this year and then to 104 percent next year, just short of the record 106 percent reached after the end of World War II.

By 2030, the CBO projects, the ratio will rise to 109 percent, compared with its pre-COVID projection of 98 percent. Longer-term, rising spending on health-related programs and Social Security drive inexorably increasing deficits even though projected low interest rates slow the rate of debt accumulation until the early 2040s. The authors, using CBO assumptions for growth and interest rates, project that the debt under current law rises to 190 percent by 2050—somewhat higher than the CBO’s pre-COVID projection of 180 percent. However, the authors caution that, with certain assumptions for continued policy, such as the extension of the 2017 tax cuts beyond their expiration date, the ratio would soar to 222 percent by 2050. They also show that the projections are sensitive to predictions about the path of interest rates.

At the state and local level, because of the unusual nature of the current recession, the authors use a bottom-up approach to estimate the pandemic’s fiscal impact rather than relying on the historical relationships between the economy and state and local tax revenues.

For instance, they estimate smaller income tax losses, in part because high-income workers—who pay more in taxes—have been less affected by the recession than low-income workers. Pandemic-related federal spending on unemployment benefits and grants to small businesses through the Paycheck Protection Program likely will boost state income tax revenue. And, because the stock market bounced back strongly over the summer, capital gains taxes won’t be significantly affected.

However, social distancing has reduced state and local taxes and fees related to health care, entertainment, gambling and, in particular, transportation. Also, the drop in consumption during this recession has been far larger than typical, depressing sales taxes. On the other hand, consumption has fallen most sharply on services, which are mostly untaxed.

The authors note that state and local governments are due to receive $250 billion in federal aid this year, including aid to public colleges and hospitals, although smaller states received much more generous aid relative to their losses than states like New York and California. In the aggregate, the federal aid this year exceeds the projected state and local revenue loss of $188 billion in 2020.

“But that doesn’t mean the aid has been sufficient to preclude tough budget choices and poor macroeconomic outcomes,” the authors write. These governments are facing a multiple year shortfall in revenue. And, because the pandemic has likely increased the need for state and local spending in areas such as public health, help for the elderly, and virtual schooling, “simply maintaining pre-COVID levels of spending may not be enough to ensure that necessary services aren’t cut,” they write.

Click here to download the data and programs for this paper.

David Skidmore authored the summary language for this paper. Becca Portman assisted with data visualization.

CITATION

Auerbach, Alan, William G. Gale, Byron Lutz, and Louise Sheiner. 2020. “Fiscal Effects of COVID-19.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall, 229-278.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST DISCLOSURE

Byron Lutz is on the board of the National Tax Association. The authors did not receive financial support from any firm or person for this paper or from any firm or person with a financial or political interest in this paper. Other than the aforementioned and positions listed on Brookings expert profiles, the authors are not currently officers, directors, or board members of any organization with an interest in this paper.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).