Earlier this month, the European Union (EU) took a decisive step towards transparency: It agreed to mandate publicly-listed European companies as well as large private firms to disclose their payments to governments for oil, gas and mining projects. This transparency is crucial in the fight for better governance of resource-rich countries. It will empower citizens with information about the amount of money their governments receive, helping them to monitor how this money is ultimately used and to deter corruption.

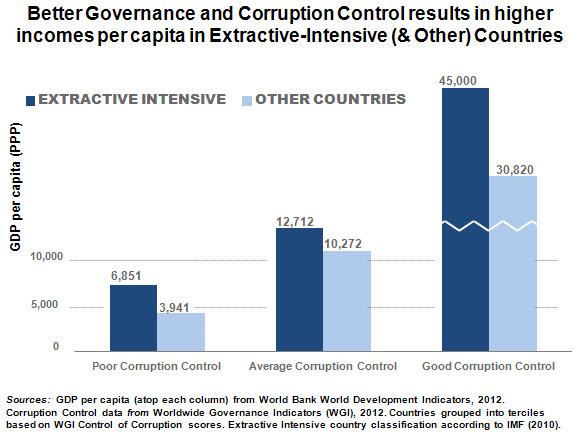

Opacity has long ties with corruption, and both are detrimental to growth. Our research shows that countries that control corruption and improve governance can triple their incomes per capita in the long term – a 300% dividend. As seen in the figure, this good governance dividend also applies to countries rich in natural resources.

The benefits of transparency dwarf the cost of disclosure. Today about 40 percent of the 1.7 billion people in resource-rich countries live in poverty, making less than $2 a day. Such poverty in the midst of immense resource wealth is due to low standards of governance and transparency, a critical issue for which oil and mining companies are also responsible.

The EU rules are part of the international community’s response to the opacity challenge, and are modeled after U.S. rules the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) released last August to implement the Cardin-Lugar amendment of the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act.

This move towards mandatory disclosure in two of the world’s largest capital markets signals what European Commissioner Michel Barnier has called a “new era of transparency.”

BIG OIL BATTLES NEW RULES

The emergence of this new global standard, however, does not mean the campaign for revenue transparency is over. While the transparency train has clearly left the station, not everyone is on board. Major multinational oil companies have been trying to water down these requirements on both sides of the Atlantic. These companies have put their reputations in jeopardy by backing the American Petroleum Institute (API) in its lawsuit against the SEC to stop implementation of the U.S. rules. Now that the EU has joined the drive for disclosure, Big Oil faces a major problem in its assault on transparency.

The new EU disclosure deal undercuts a number of API’s arguments. API’s inflated estimates of compliance costs are now increasingly irrelevant, as major cross-listed companies, like Shell and BP, will have to comply with EU rules regardless of the lawsuit’s outcome. API’s claims that the SEC acted arbitrarily by adopting the U.S. rules – already questionable given that Congress mandated the rules and the SEC conducted an exhaustive public comment process during its rulemaking – are also undermined by the EU’s agreement to adopt very similar measures. The EU legislation will, in fact, encompass more than the U.S. rules as it covers large, privately held companies (and the timber sector), in addition to publicly listed companies.

And API’s argument that the rules cause competitive harm is even less compelling since the EU will apply analogous rules to companies under its jurisdiction, helping to level the playing field. Together, the U.S. and EU regulations will cover capital-markets listed companies, accounting for nearly 70 percent of the market capitalisation of extractive industry firms on the world’s most significant stock exchanges.

SECRECY DAMAGING REPUTATIONS

By continuing to support API’s lawsuit, companies are incurring significant costs defending opacity, not only pecuniary, but reputational as well. The public is becoming increasingly aware of their fight against transparency. While a few companies are taking some steps away from secrecy – Norway’s Statoil disavowed support for the API lawsuit – they are still the exception.

Shell, for instance, faced setbacks when Alan Detheridge, one of its former executives, openly criticized the company’s efforts to block U.S. and EU transparency, and the Dutch government pledged its support for strong EU rules consistent with U.S. law. The company has now started to change its tune, claiming it has supported mandatory reporting requirements all along – an assertion The Economist wryly noted contradicts Shell’s membership in API and refusal to disavow support for the U.S. lawsuit.

Oil companies should draw lessons from Shell’s mishaps, seizing the moment to actually “walk the talk” on transparency. Instead of litigating against transparency, companies should focus on complying with the U.S. and EU rules and enlist their lawyers to prepare for new reporting. Companies covered by the U.S. and EU rules should also join the global transparency movement to ensure these disclosure standards apply to all relevant companies. Obtaining a G8 commitment to mandatory disclosure at this year’s Summit would bring key countries like Canada into the fold. An effort to enact similar legislation in additional markets, including Australia and emerging Asian and South American economies, should follow.

The U.S.-EU legislative consensus on a global standard of transparency is a watershed moment for improving the governance of natural resources worldwide. Big Oil should not stand in the way. To restore their credibility and support good governance and development around the world, oil companies should publicly state their intent to comply with the new disclosure standards and urge API to drop its lawsuit.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edEra of Big Oil Secrecy is Over

April 24, 2013