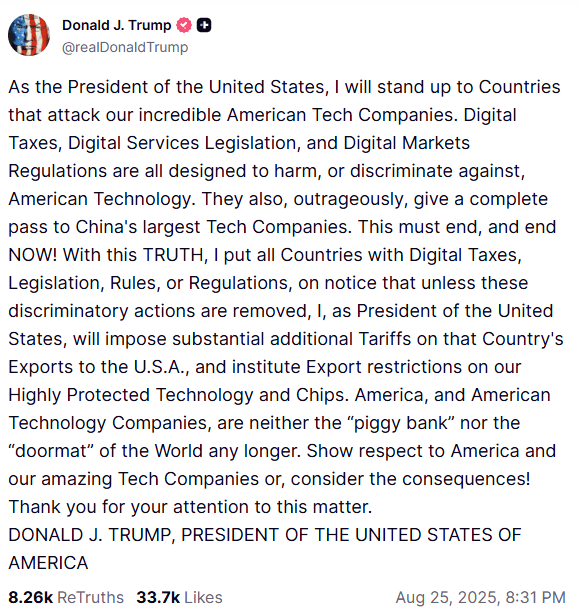

President Donald Trump appears to be trying to recreate 17th-century mercantilism for the 21st-century digital economy. Back in August, responding to European regulations that expect responsible behavior by the dominant digital companies, he wrote on Truth Social, “As the President of the United States, I will stand up to Countries that attack our incredible American Tech Companies.”

Centuries ago, European governments protected favored firms operating abroad. As this Truth Social post illustrates, the dominant American digital companies—Big Tech—have been similarly successful in cultivating President Trump to protect them from the regulatory expectations of other nations, especially Europe.

Digital mercantilism

From the 16th through the 18th century, European nations used tariffs, monopolies, and political power to shield favored companies. This policy, called mercantilism, created winner-take-all opportunities for the politically privileged.

Mercantilism once protected companies from competition. Trump’s digital mercantilism protects a business model.

The dominant digital platforms of the internet became monumentally profitable in part by avoiding costs associated with responsible behaviors such as protecting user privacy, accountability for the content they distribute, and avoiding anticompetitive behavior. Economists call this “externalization”—the shifting of burdens that should be the responsibility of a company to users and society.

When President Trump speaks of “Digital Services Legislation,” he is referring to the EU’s Digital Services Act (DSA) and the expectations it establishes for platform-delivered content. The expression “Digital Markets Regulation” refers to the Digital Markets Act (DMA), designed to protect competition in online markets. Apparently, he sees requiring dominant companies to be accountable to the public interest as an act “designed to harm, or discriminate against American Technology.”

What President Trump leaves out

President Trump’s post is missing any recognition of the interests of American citizens, focusing instead on the corporations whose practices have harmed those citizens.

Because of the absence of American regulatory oversight, these companies have, among other things, engaged in monopolistic behaviors, avoided responsibility to the truth in what they distribute, designed their products to be addictive, and violated the personal privacy of their users—all for the purpose of expanding profits.

The EU has attempted to rebalance the market by requiring dominant companies to accept responsibilities they have worked to avoid. On the other hand, the president of the United States seeks to protect the magnification of Big Tech’s profits through the reduction of its responsibilities.

This approach marks a sharp departure from the U.S. government’s traditional treatment of American industry. Automobile manufacturers, for instance, must bear the costs associated with producing a safe product, such as installing airbags, seatbelts, or emission controls. In contrast, Big Tech has been able to sidestep the costs of addressing its own safety problems, such as misinformation, addictive use by young people, and the adverse consequences of creating an information ecosystem solely designed to maximize advertising revenue.

In this new form of mercantilism, the president is threatening “substantial additional Tariffs” on European exports to the U.S. so that Big Tech companies may continue to avoid costs they should have already been internalizing as a part of being good corporate citizens.

When companies make their own rules

Since the dawn of the digital era, Congress has largely avoided establishing expectations of responsibility for online services. In the absence of such standards, companies have been able to make their own rules and prioritize profits over accountability.

The Silicon Valley mantra “move fast and break things” has served as a roadmap in this sense. To “move fast” was essential; new behaviors had to become ingrained before anyone caught on to what was really being done. The “things” to be broken, of course, were the norms and standards of marketplace behavior that previously provided stability.

Such a do-it-quick-and-the-consequences-be-damned attitude proved highly profitable. Yet, because it also drove innovation and produced impacts that were hard to foresee, American policymakers turned a blind eye to its consequences.

Over time, the small and innovative startups became giants, amassing economic and political power. By the time everyone was using the new platforms and the “consequences-be-damned” results became visible, the need for meaningful oversight manifested; however, the companies were powerful enough to resist the expectations of responsibility.

What worked in Washington, however, did not work in Brussels. With the passage of the DMA and DSA, EU institutions established guardrails that the dominant digital companies had previously been able to ignore.

New regulatory model

What makes the EU’s approach especially significant is its largely unrecognized break with traditional regulation. Industrial-era regulation relied on the micromanagement of corporate activities to achieve public interest goals. The DSA and DMA, however, create a different paradigm that sets behavioral expectations for the companies to achieve on their own terms.

The DSA, for instance, mandates that companies must incorporate content moderation and transparency into their operational decisions. Unlike traditional regulation, the law does not specify how these goals must be met, but rather mandates that they be achieved in a meaningful manner. It is then up to the company to self-certify its compliance and face penalties if it falls short.

Similarly, the DMA establishes the expectation of self-executing compliance without prescribing specific corporate behavior. Its focus is on fostering marketplace choice by ensuring that competitors have a genuine opportunity to contest for the market. Companies are then required to certify how their practices promote contestability and fairness.

The European oversight that President Trump seeks to punish is more nuanced than the traditional, blunt-force regulatory micromanagement model invented in the United States during the industrial period. Instead of “we will tell you how to run your business,” it’s now “we will identify the desired public interest and expect you to achieve it.”

Sovereignty

The EU’s digital regulations are an exercise of sovereignty. Both the U.S. and EU nations regularly exercise such sovereignty over goods and services offered within their borders. American car makers, cosmetics companies, medical device companies, toy manufacturers, aircraft manufacturers, and more must obey rules established by the EU before they can sell their goods in that market. Similarly, European automobiles must meet American safety and emission standards. Imported food products must comply with the regulations of the Department of Agriculture and the Food and Drug Administration.

Digital goods are no exception. When, for instance, the president dictates conditions for TikTok to operate in the U.S., he exercises national sovereignty over a digital product. The EU is behaving similarly with the DMA and DSA.

Despite these parallels—and decades of mutually beneficial trade—Donald Trump is demanding the EU to “Show respect to America and our amazing Tech Companies” and to “end, and end NOW!” its digital market regulations. It is a 21st-century reprise of mercantilism, with the government as the enforcer on behalf of its most powerful corporations.

“They jokingly call me the ‘president of Europe,’” Donald Trump said in the Oval Office after meeting with assembled European leaders on August 26. What was meant as bravado is a revealing self-portrait of a transactional president. This time, the president seeks to assert dominion over the regulatory sovereignty of other nations in order to shield the profits of Big Tech.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Donald Trump’s digital mercantilism

October 8, 2025