The data referenced below regarding vaccination rates by race/ethnicity is outdated. As of today, the CDC is reporting that Native Americans have the highest vaccination rate, as opposed to Asian Americans, as cited in the article.

With the delta variant fueling an explosion of positive COVID-19 cases across the country, it is becoming even more critical to address sources of vaccination hesitancy. Researchers have provided a range of explanations for vaccination hesitancy, including partisanship and political ideology, lack of trust in the federal government, and misinformation about the safety of the vaccines; however, there is little to no research examining the role of discrimination on vaccination status.

The African American Research Collaborative/Commonwealth Fund American COVID-19 Vaccine Poll is an extensive, diverse national survey with measures of discrimination experiences, COVID-19 vaccination status, and vaccine hesitancy. Drawing on this survey, we test the relationship between discrimination and vaccination uptake. We find that a significant segment of the national sample has experienced discrimination when interacting with the health system, and that these experiences influence their decision on whether to get vaccinated. It seems that this is another example of how structural racism harms both individual Americans and the wider population.

Discrimination and Health Outcomes

Discrimination experiences are a dominant condition for racial and ethnic populations in the United States. As such, scholars in public health and social sciences have documented the negative impact that discrimination has on health outcomes.[i] Although much of this work focuses on the implications of discrimination among African Americans, there are a growing number of researchers exploring the same relationship among other groups, including Latinos and Native Americans. For instance, researchers have found that Native people report experiencing discrimination at higher rates than whites when seeking health treatment; some Native American women have even been unknowingly sterilized.

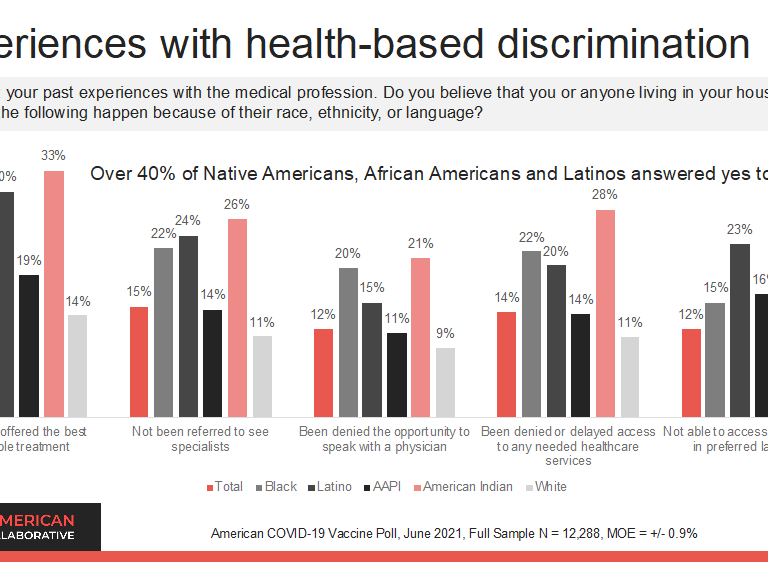

The strength of our analysis is that we isolate specific discrimination experiences in the healthcare system. For example, one of the most common experiences among patients of color is not being offered the same medical treatments or options as white Americans; however, this is not just a recent phenomenon. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Discrimination in America surveys document that nationally, people of color reported higher rates of discrimination when interacting with the healthcare system. Discriminatory behavior perpetrated against people of color is often attributed to implicit bias and, unfortunately, has been even more apparent during the pandemic. For example, President of Wayne State University, Dr. M. Roy Wilson, contributed the lack of testing of Black individuals to implicit bias: “There is some evidence that African Americans with symptoms have not been tested as frequently.” There is also evidence that Latino adults lacked access to Coronavirus testing early in the pandemic.

Similarly, racial discrimination has also increased during the pandemic. The most evident and dangerous example of discrimination was the racialization of COVID-19 blame directly targeting Asian Americans. These communities faced anti-Asian violence and other forms of hostility stroked by the rhetoric of President Trump, which has ultimately accelerated anti-Asian Xenophobia. Communities of color beyond Asian Americans have also been subject to discriminatory treatment during the pandemic, including being blamed for high infection rates. This, understandably, may impact their views toward the vaccination process.

Data and Methods

As formerly mentioned, the 2021 African American Research Collaborative/Commonwealth Fund American COVID-19 Vaccine Poll surveyed more than 12,000 individuals nationwide, with large samples of African Americans, Latinos, Asian American/Pacific Islanders, and Native Americans. It is designed to understand individual hesitancy and barriers to the COVID-19 vaccine; by drawing on these measures, as well as measures of discrimination experiences, we can directly explore how healthcare discrimination impacts vaccination uptake. This is particularly relevant as the nation takes aggressive steps to increase vaccination coverage. A full discussion of the methodology is available here.

Discussion of Descriptive Results

The survey identifies that healthcare discrimination is, unfortunately, a common experience for racial and ethnic minorities. According to the survey, more than 40% of Latino, African American, and Native American adults have experienced discrimination within the healthcare system; for instance, not being offered the best available treatment is the most identified experience for respondents. Members of the African American and Native American communities are the most likely to report negative medical experiences; however, Latinos are the most likely to report having language barriers block access to medical care. The Asian American/Pacific Islander population is the least likely of the major racial and ethnic minority groups to report medical discrimination. Coincidentally, they are also the population with the highest vaccination rate. white Americans are the group least likely to report unfair discrimination experiences in the health care system across all measures in the vaccination survey.

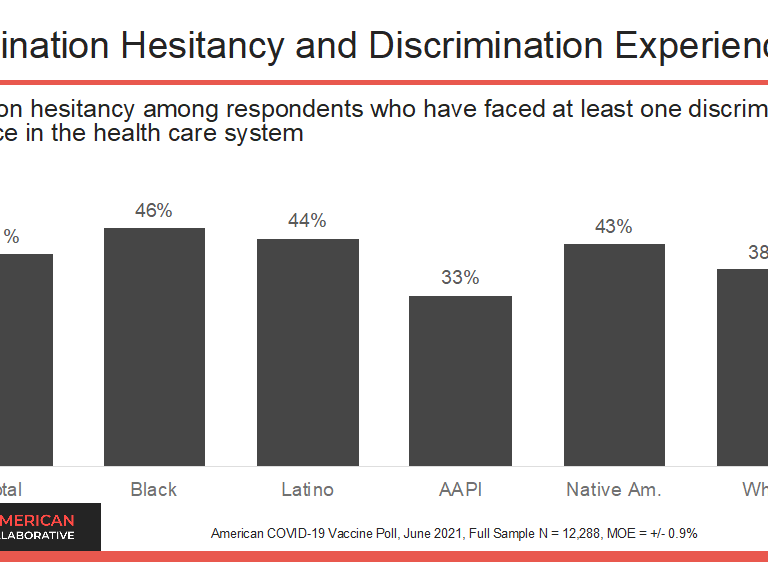

Next, we explore whether there is a relationship between these discrimination experiences and vaccine hesitancy. We do this by recording whether respondents answered “yes” to at least one of the discrimination questions and pairing it with their reported vaccine status. Then, we focus solely on the respondents identified as being vaccine-hesitant, which are those who reported not yet getting the vaccine. The graph below isolates respondents who have expressed vaccination hesitancy in the survey and have also experienced at least one form of discrimination experience within the health care system. The graph suggests that the influence of discrimination experiences on vaccination hesitancy is more pronounced for African American, Native American and Latino Americans.

Unvaccinated respondents were asked for their reaction to the statement that “members of their racial group face discrimination from medical professionals which makes it hard to trust the COVID-19 vaccines are safe and effective for themselves and others from their community.” This is a more direct assessment of the implications of discrimination on vaccination uptake. Among all racial and ethnic minority respondents, 39% reported that they had heard about this issue, with 16% reporting that it has made them less likely to want to get a vaccine. Consistent with the differences in discrimination experiences, African American and Native American respondents were more likely to report that racial discrimination directed towards their community makes trust in the vaccine more difficult. More specifically, 27% of Black and 22% of Native American respondents reported that racial discrimination has made them less likely to get a vaccine. This is significantly higher than Latinos (14%) or Asian American/Pacific Islanders (16%).

Conclusions

Discrimination remains a crucial factor in shaping the lives of people of color, especially in healthcare access and treatment. These historical and contemporary experiences shape willingness, or lack thereof, to receive the COVID-19 vaccine. It is not widely recognized that for many Americans of color, deciding to get the vaccine requires trust in a medical system that has not been shown to treat them fairly or prioritize their communities. Consequently, these experiences directly impact vaccination uptake through vaccination hesitancy, particularly among African Americans and Native Americans.

When discussing vaccine rates by race, it is vital to include the role of healthcare discrimination as a source of vaccine hesitancy. As the nation becomes more familiar with structural racism and systemic discrimination, this analysis provides a clear example of how powerful these concepts are in shaping the behavior of Americans who face unfair treatment in healthcare due to their race/ethnicity.

Footnotes

[i] See the following review article for a summary of this literature: https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/abs/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750/.

About the Authors

Gabriel R. Sanchez, Ph.D., is a David M. Rubenstein Fellow in Governance Studies, a Professor of Political Science, and Founding Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Chair in Health Policy at the University of New Mexico. Sanchez is also the Director of Research at BSP Research.

Matt Barreto, Ph.D. is Matt A. Barreto is a Professor of Political Science and Chicana/o & Central American Studies at UCLA and the co-founder of the research and polling firm BSP Research.

Ray Block, Ph.D. is the Brown-McCourtney Career Development Professor in the McCourtney Institute and Associate Professor of Political Science and African American Studies at Penn State University.

Henry Fernandez is CEO of the African American Research Collaborative and the CEO of Fernandez Advisors, a consulting firm that counsels clients in management, planning, project development, and political strategy. He serves as a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress.

Ray Foxworth, Ph.D. is Vice President of First Nations Development Institute, a Native American-led community and economic development organization, and is a visiting scholar in the Department of Political Science at the University of New Mexico.

Commentary

Discrimination in the healthcare system is leading to vaccination hesitancy

October 20, 2021