In an increasingly unstable climate, a community’s capacity to reduce the impacts of disasters and extreme weather and bounce back when they occur—what’s known as “resilience”—is vital to saving lives and money. Put simply, lawmakers’ consistent failure to reduce, plan for, and adapt to the impacts of climate change is imposing an implicit tax on Americans. And while they can’t pass legislation to stop storms and wildfires, elected officials across levels of government have the power to reduce this tax by instituting policies that contribute to an evidence-based, bipartisan national climate resilience system.

Disasters and extreme weather are economic disruptors, preventing Americans from going to work and drawing a paycheck. Since 1980, there have been over 400 disasters in which damage exceeded $1 billion, causing a combined $2.9 trillion in economic impacts. In 2024 alone, a major disaster was declared every four days, causing 568 total deaths and billions of dollars in damages to homes and community lifelines such as hospitals, businesses, roads, and other major infrastructure. These events destroy public infrastructure, straining municipal and state budgets; they erode aspirations of homeownership, causing more regular damage to homes and increasing insurance premiums; and they can raise household costs, spiking energy prices as heatwaves and cold snaps occur more frequently.

Indeed, many of the most disaster-prone regions are locked in cycles of disaster response and recovery. While federal policies and programs for resilience exist, they have largely sprawled out of the federal emergency management system, creating a patchwork of laws and policies with little overarching national strategy. This hodgepodge of programs manages to underfund climate resilience while also unevenly allocating funding such that states and municipalities—which are more highly resourced, and thus better placed to respond to risks—tend to receive the lion’s share of funding. Importantly, the absence of a federal system is limiting our capacity to respond to new threats that are posing an increasing risk to people and infrastructure, including sea level rise, heatwaves, droughts, and cold snaps.

By exploring federal programs as well as state and local planning for climate resilience, this report poses a simple question: How are decisionmakers responding to climate risks? Starting at the national level, the report discusses the federal programs that provide funding for state and local investments in resilient infrastructure and technical assistance, as well as the limitations with the current federal system.

Then, drawing on Brookings analysis of data from the Georgetown Climate Center, the report charts the rise of resilience planning at the sub-national level—mapping which states, municipalities, and regional coalitions are implementing resilience plans. While climate resilience has become more contested federally as recent administrative actions freeze or claw back resilience grants, at the sub-national level, planning for climate resilience is more common than one may think. Municipal planning in particular has become more comprehensive and widespread, demonstrating that planning for climate impacts continues to be normalized as a function of governance.

This report is the first in a new series on climate resilience. Future reports will examine how federal and state policies and innovations in governance, insurance, housing, and other areas can bolster community-level climate resilience, and in so doing, reduce the costs that climate change is placing on American lives and livelihoods

What is climate resilience?

Climate resilience refers to a community’s ability to bounce back from a sudden shock (such as a hurricane) or a chronic shock (such as sea level rise) in ways that reduce climate risks over the long term by facilitating learning and transformation.

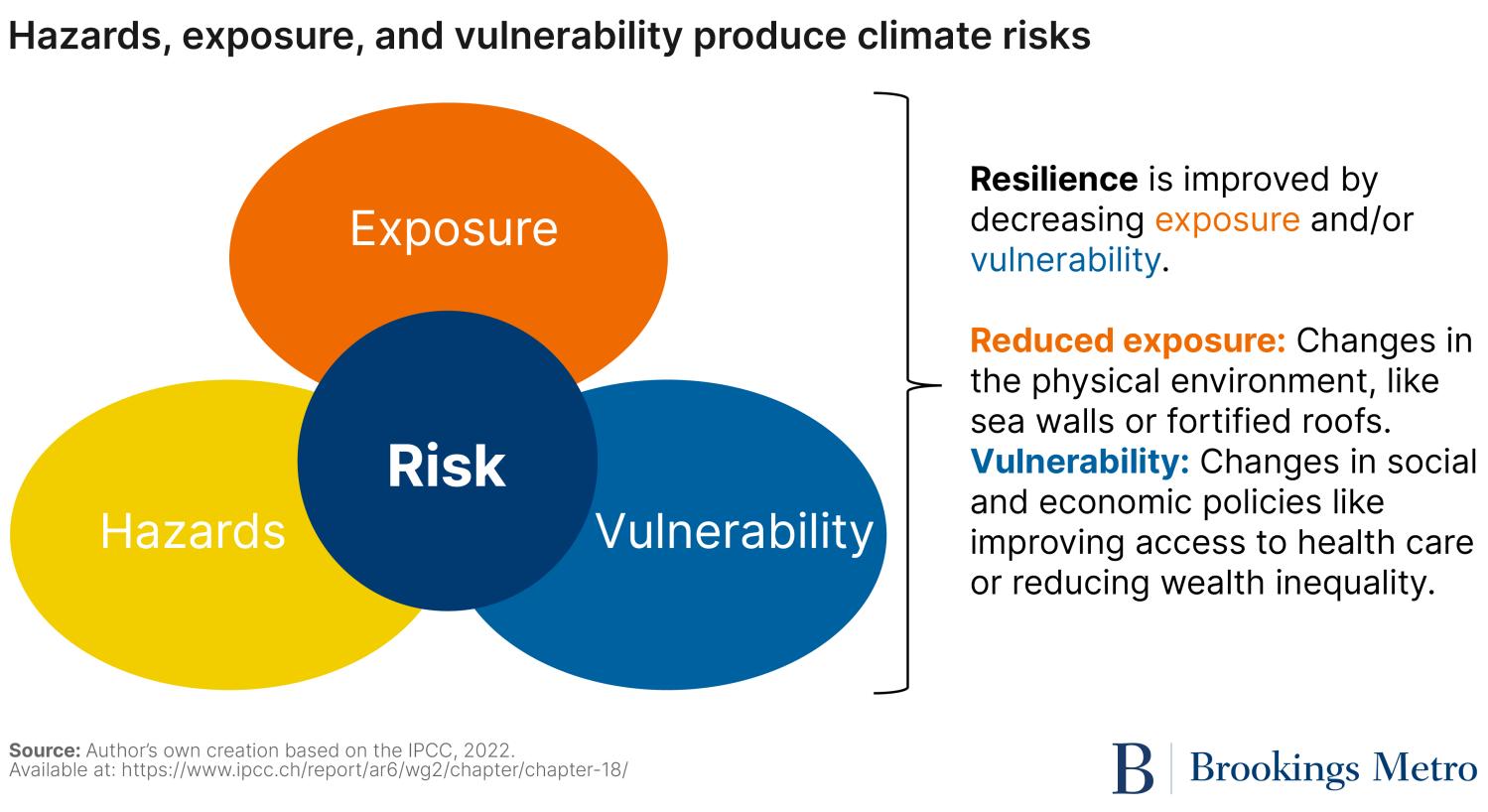

But how do the actions of government help reduce climate risks and build climate resilience? Because climate risks are not only a product of physical events such as temperature extremes, but are also due to socioeconomic factors such as poverty (which can amplify impacts), building resilience takes changes in social and economic policies as well as the built environment. As Figure 1 shows, climate risks result from at least three distinct factors:

- Hazards: The physical events themselves, such as hurricanes, storms, and wildfires

- Exposure: How susceptible human structures such as roads and homes are to being impacted by hazards

- Vulnerability: The social and economic circumstances of communities and individuals, including wealth and access to health care, that can moderate the impacts of hazards

Because policies and infrastructure can’t themselves reduce the occurrence of hazards, bolstering resilience occurs through changes in either exposure or vulnerability. For example, alterations in the built environment such as fortifying roofs and building sea walls can help reduce exposure to coastal storm surges, while new social and economic programs such as subsidizing affordable housing can reduce vulnerability by decreasing the likelihood that a hazard will cause chronic financial stress.

Resilience policies are most effective when they target exposure and vulnerability together. For example, a community where flooding is infrequent may still have high climate risks if homes are in flood zones and most residents are low-income renters without flood insurance. Similarly, a community with frequent flooding may be low risk if housing is raised and robust social and economic programs are available to aid families that are displaced or temporarily unemployed.

The federal resilience system is unnecessarily complex, and leaves communities underprepared for changing risks

In their current form, federal laws and programs for climate resilience are falling short of needs. Unlike 87% of countries globally, the U.S. has no federal legal or policy structure to facilitate and coordinate nationwide resilience planning. Instead, a complex, fragmented, and piecemeal national structure has evolved, spreading across numerous laws, departments, and programs with complex statutory authority and responsibilities. In terms of dollars spent, this system is over-indexed toward disaster recovery rather than resilience—and in some cases, is leading to unequitable outcomes.

Many policies that target climate resilience are connected to the sprawling federal disaster and emergency management system, which itself spans multiple agencies and laws. For example, programs to reduce community-level exposure to disasters through building more resilient infrastructure—such as the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) program, the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Hazard Mitigation Assistance Grants, and the 2021 STORM Act—were all enacted through amendments to the 1988 Stafford Act (the foundational law for federal disaster response). Meanwhile, the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) programs, including CDBG-Mitigation, which explicitly funds resilience, were enacted through the statutes associated with the 1974 Housing and Community Development (HCD) Act.

Further still, other laws that largely provide funding for more resilient public infrastructure—such as provisions under the 2014 Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation (WIFIA) Act, which provides resilience dollars for municipal water management, and the 1976 Energy Conservation and Production (ECPA) Act, which authorizes grants under the Department of Energy for fortifying homes—are disconnected from the Stafford Act and the other laws that govern most emergency response functions.

Arguably more influential than statutory regulations are indirect contributors that shape the fiscal and municipal planning environment. These include rules under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which governs how federal agencies plan public infrastructure, and the government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) insurance requirements, which set the rules around home and property insurance as well as risk-reporting standards.

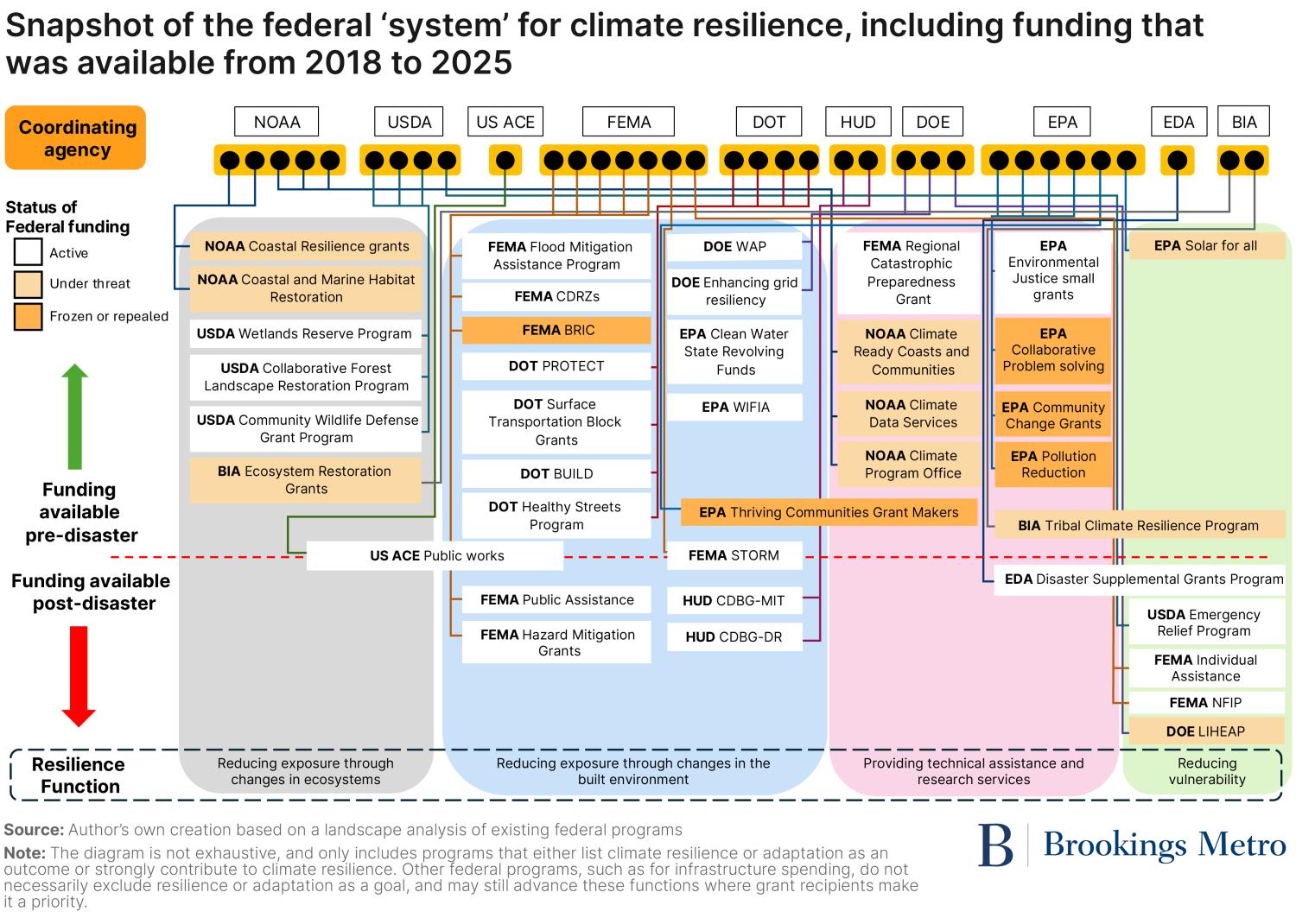

To provide an indication of the complexity of the federal system, Figure 2 shows a non-exhaustive list of federal programs that provide funding to bolster climate resilience at the state and/or local level, as well as the agencies responsible for coordinating those programs. These programs are sorted into four domains of resilience planning: 1) reducing exposure through changes in the built environment; 2) reducing exposure through changes in the natural environment; 3) reducing vulnerability through social and economic programs; and 4) providing technical assistance and research services to improve state and local adaptive capacity. While not exhaustive, the figure shows the diversity of program types, functions, and—as discussed later in this report—the current status of funding. Several programs whose primary function is not resilience but that nevertheless bolster resilience through providing a financial safety net for households are also listed under the “reducing vulnerability” function, including the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program (LIHEAP), the National Flood Insurance Program, and post-disaster aid such as FEMA’s Individual Assistance.

Figure 2 shows that major programs span at least 10 agencies, with 39 separate programs—although the true number is likely higher, as the figure excludes programs that indirectly contribute to climate resilience. Many of these programs are managed by three agencies: FEMA, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Their functions span from managing competitive grants processes for new infrastructure to providing technical assistance and research services for local and state agencies to conduct vulnerability assessments. While many of these programs, such as U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ public works and the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s CDBG program are geared toward reducing exposure through changes in the built environment or ecosystem restoration, few programs target reductions in social vulnerability, particularly in terms of pre-disaster risk reduction.

These laws and programs are an imperfect fit as a foundation for a comprehensive climate resilience system. Overall, the funding available to states, regions, and municipalities to build climate resilience is small compared to both the funding available for disaster response and recovery as well as the demand from communities. From 2019 to 2023, FEMA spent an average of $39.5 billion in annual and supplemental appropriations for disaster response and recovery. A recent Government Accountability Office report found that by 2050, the federal government could spend between $26 billion and $134 billion annually (in 2021 dollars) on disaster response and recovery.

While FEMA does set aside funds for risk mitigation, the majority is only available to states and communities after a disaster strikes. Between FY 2010 and FY 2018, 88% of FEMA grants that target resilience (delivered primarily through the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program and Public Assistance) were only available after a federal disaster declaration was given. With the passing of the Disaster Recovery Reform Act in 2018, and later the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), Congress has increased the funding available for resilience before a disaster occurs. However, post-disaster funding still dwarfs pre-disaster funding.

States and municipalities have been quick to make use of available funds, particularly where federal dollars are more flexible and allow grantees to set their own priorities for resilience. For example, requested funds for the BRIC program, which started granting in 2020, have increased each year of the program’s existence, reaching $5.7 billion in 2023—yet the funds available have hovered around $1 billion annually (although spiking in 2022 at $2.4 billion). Programs such as Promoting Resilient Operations for Transformative, Efficient, and Cost-Saving Transportation (PROTECT) Formula Program, implemented under the IIJA to provide funding to make surface transportation more resilient to hazards, has a larger annual spend ($1.5 billion in 2025), but more limitations in how funds can be spent.

While more flexible funding such as BRIC has increased federal spending on climate resilience, these programs have not been without problems. Recent research shows that funding under BRIC has consistently benefited wealthier communities over disadvantaged ones where funding is needed most. In 2023, 78% of BRIC funding went to East Coast and West Coast states, where local government agencies tend to be better resourced and have a greater capacity to apply for funding. Part of the problem is that the tools developed to support grant distribution, such as the National Risk Index, consistently underestimate the role of vulnerability and overestimate exposure in assessing disaster risks. This can lead to communities with higher private and commercial property values—and thus, higher expected losses from disasters—being prioritized for funding over communities where social factors such as high poverty rates and rental precarity are driving vulnerability.

Once a bipartisan issue, resilience planning at the federal level has been caught in political battles

Despite these limitations, there is a larger issue looming. The current system is breaking down under the growing impacts of climate change as they become more widespread; for example, deaths from heatwaves (which are not eligible for federal disaster declarations) now contribute to more deaths annually than all other disasters, including hurricanes, flooding, and wildfires combined. Yet calls for climate resilience have become politically contentious. A clear tension has developed between the reality that climate change is impacting more communities and infrastructure on one hand, and polarization over climate action on the other. Recently, this tension has had real consequences, stripping communities of access to federal resources and limiting the availability of public data and decision-support tools.

In 2022, planning for a federal climate resilience system began in earnest. The Biden administration introduced the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), a spending program to modernize infrastructure, which included $369 billion to spur climate adaptation and decarbonization. The climate dollars authorized under the IRA—and to a lesser extent under the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA)—were intended to subsidize consumers to purchase greener technologies, help state and local governments build capacity, develop a financial ecosystem to fund adaptation and decarbonization projects, and fund more resilient infrastructure at the state and local level as well as for Tribes. Some of this funding emphasized justice and racial equity as a policy goal, including the development of new data tools to help identify historically underfunded and highly vulnerable communities for prioritized investments. Republicans fiercely opposed these efforts, portraying them as frivolous spending that was advancing economically destructive and unfair policy.

Then, in 2023, the administration developed the first National Climate Resilience Framework—a policy guide detailing the responsibilities and expectations for federal, state, and local government, as well as philanthropy and the private sector, in tackling the impacts of climate change on individuals and communities. On January 10, 2025, 10 days before the inauguration of the Trump administration, the Biden administration quietly released the National Adaptation and Resilience Planning Strategy—the nation’s first real scaffold for a national resilience system.

Unsurprisingly, the Trump administration has rescinded large portions of the IRA, including curbing spending on renewable energy generation and revoking policies for environmental justice. While the focus has been on dismantling regulations and policies supporting decarbonization, climate resilience planning has been caught in the crosshairs. Figure 2 shows that over the course of 2025, the Trump administration has frozen or clawed back over $5 billion in funding for climate resilience and adaptation that was allocated under the IRA. Within that total, the administration has terminated the bipartisan BRIC program, which would have provided around $582.8 million in federal funds for climate resilience in 2025, and cancelled an estimated $882 million in previous BRIC awards from 2020 to 2023. The Trump administration has also made it harder for states and regions to plan for climate impacts by disbanding the National Climate Assessment and defunding functions of NOAA to monitor disaster impacts and provide research services.

There is an argument that the Trump administration was given a mandate to take these actions, and they are not necessarily misaligned with voters’ preferences either. Indeed, voters’ concerns over climate change have become more polarized over the last 15 years. In 2024, an estimated 47% of moderate Republicans and 24% of conservative Republicans said they were somewhat or very worried about climate change, compared to 94% of liberal Democrats and 87% of moderate Democrats. This is despite the fact that a larger number of Americans have been impacted by extreme weather, disasters, or sea level rise over the same period. However, voters don’t always connect disasters and extreme weather to climate change, even when they themselves are impacted. For this reason, voters may be unwilling to support climate action even when the intended outcome is resilience rather than shuttering oil and gas facilities.

The Trump administration does seem to understand this dynamic, being opposed neither to the concept of resilience nor to the goal of reducing the risks of natural hazards. For example, a March 19 executive order, “Achieving Efficiency Through State and Local Preparedness,” establishes a process for developing a “National Resilience Strategy.” Avoiding the term “climate change,” the executive order connects resilience to national security, cyber threats, extreme weather, and disaster response. Yet despite a commitment to publish before late June, this strategy has yet to publicly materialize. To be clear, the Trump administration has taken actions that have reduced the availability and accessibility of resilience funds. However, at least in words, the administration has signaled its commitment to resilience even if it’s not willing to use the term “climate.”

While it’s difficult to assess the ultimate aims of the administration, a January 24, 2025, executive order and FEMA’s recent slow-walking of federal disaster declarations appear to make one position clear: State, regional, and municipal governments, rather than the federal government, should bear most costs for disaster recovery and risk reduction.

At the state and local level, resilience planning is more comprehensive and widespread

In this increasingly politicized federal system, it would be easy to assume that climate resilience planning in the U.S. has stalled or is even moving backward. However, exploring the sub-national level reveals that many states and municipal governments are making tremendous progress.

Map 1 shows that most states (33 in total) have undertaken some form of resilience planning since 2008, including publishing a state resilience plan, launching a state resilience or adaptation agency, appointing a chief resilience officer, or launching a resilience or adaptation taskforce. Twenty-four states have published resilience or adaptation plans, with 58.3% (14) of the plans published or updated within the last five years, and 87.5% (21) published or updated within the last 10 years. Twenty-nine percent of states (15 in total) have resilience and adaptation offices that bear responsibility for climate resilience planning. A further four states are in the process of developing a resilience plan, having organized resilience or adaptation task forces.

These plans vary in their comprehensiveness and implementation. For example, Florida’s Energy and Climate Change Action Plan, updated from an earlier plan from 2008, responds to a limited range of natural hazards (sea level rise, coastal erosion, and flooding), and adopts a strategy to bolster resilience largely through reducing the exposure of coastal infrastructure and housing. Meanwhile, California’s Climate Adaptation Strategy—and recent updates, including the Safeguarding California Plan—target a wider range of hazards and social and economic policy changes, guided through progressive principles including economic justice and racial equity.

Thirteen states have made climate resilience a priority by appointing a chief resiliency officer (CRO) tasked with overseeing resilience planning across the state. The earliest of these came in 2014, after Virginia passed a state statute to appoint a CRO, and as late as 2023, with the appointment of a CRO in Maryland under Governor Wes Moore. While these positions are relatively new (and in most cases have only held planning authority rather than control over state resources), the adoption of CROs is an indication that a growing number of states recognize the importance of resilience planning.

At the state level, not only is climate resilience planning more common than might be expected given the fraught federal policy environment, it also isn’t necessarily correlated with political affiliation. Almost all coastal states—including predominately Republican-voting states such as Louisiana, Mississippi, Florida, and South Carolina, but excluding Georgia, Texas, and Alabama—have adopted state resilience plans or appointed CROs. These states have fewer voters than the national average who believe that climate change is affecting the weather, so this likely reflects the reality of disasters in these states. The earliest plans, such as those adopted in Louisiana after Hurricane Katrina, focused on regions that were already more disaster-prone, aiming to reduce exposure to hurricanes, floods, and coastal erosion. Indeed, this pattern breaks down in interior red states, with few of them having resilience plans despite the increasing risks of droughts, heatwaves, and cold snaps.

Municipal, county, and regional governments across the US have embraced climate resilience planning

Many municipalities and county governments, as well as regional coalitions, are in the process of implementing climate resilience plans. Implementation is taking place across all states and the District of Columbia, with a wave of planning having started as early as 2010.

Updating data originally compiled by the Georgetown Climate Center from 2005 to 2022, Figure 4 captures the total number of cities, counties, and regions that have published resilience plans, and also tracks how those plans have changed over time. The figure excludes instances where plans have been updated, and also tracks how resilience is articulated—moving from a purely physical concept that focuses on exposure in earlier plans to a physical and social concept that also considers inequity and injustice in more recent plans.

Figure 4 shows that 272 sub-national entities have undertaken some form of climate resilience or adaptation planning since 2005. Fifty-five government entities—including major cities such as Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago, as well as uniquely exposed cities such as New Orleans, Norfolk, Va., and Miami—have undertaken two or more rounds of planning, with 347 plans published in total. Brookings analysis of these plans demonstrates that over time, municipal resilience plans have become more complex—responding to a wider variety of hazards, and involving a greater emphasis on social vulnerability, justice, and equity as core components of climate resilience.

The rise of resilience planning—and the content of the plans themselves—have followed international and U.S. policy trends. Arguably the largest influence came between 2013 and 2019, with the launch of the multibillion-dollar philanthropic project 100 Resilient Cities—an international program to help cities across the world plan for and adapt to the impacts of climate change. In the U.S., these cities included New York, Boston, Norfolk, Va., Los Angeles, Berkeley, Calif., Dallas, New Orleans, and Atlanta. While the program was dissolved in 2019, it was influential in repositioning cities, rather than nations, as important drivers of climate resilience. Visible in Figure 4, the program also helped to normalize vulnerability reduction through social programs as an aspect of resilience. To a lesser extent, justice and equity were also normalized as targets for municipal climate resilience planning. Between 2013 and 2016, for example, 75 plans were published or updated in the U.S., and 22 included social equity as a metric to measure progress toward climate resilience (though how equity was framed varied considerably across cities).

A further set of plans was developed in response to funding made available under the IRA. The act created the Climate Pollution Reduction Grant, managed by the EPA, which provided funding for states, local governments, and Tribes to develop greenhouse gas emissions reduction plans (named Priority Climate Action Plans, or PCAPs, and Comprehensive Climate Action Plans, or CCAPs), which most municipalities took as an opportunity to plan for climate resilience. These were required for municipalities to apply for further funding under the IRA, and mostly published in 2024 and 2025, with a number of plans still undergoing public review.

In some states, such as California and Massachusetts, developing municipal- or county-level resilience plans has been required by state law and supported by state funding. In part due to these state laws that have spurred planning, municipalities in California and Massachusetts represent over 24% of all plans that exist nationally. In other states, such as Florida, resilience planning has followed a more regional approach, with municipalities and counties forming coalitions to advance climate resilience. The Southeast Florida Regional Climate Change Compact, for example, which has existed since 2009, presents a consolidated vision for climate resilience across Miami-Dade, Broward, Monroe, and Palm Beach counties.

While planning and implementation is happening in many municipalities, there are some important caveats. First, the depth and rigor of planning can vary considerably, including the definition of basic terms such as “justice” and “equity.” According to recent research, of the 58 out of the 100 largest cities with climate action plans, 40 included the term “justice” either as an aspiration or a focus of planning, while only 20 explicitly planned for improvements in justice. Importantly, this report has not assessed how plans were developed, including their mechanisms for engaging communities during plan development or throughout implementation, nor the extent to which planning reflects constituents’ attitudes and preferences. Neither does this report review progress in implementation or the extent to which planning has so far delivered actual outcomes. These are all critical questions for further research.

Municipal and state activity show there is a clear demand for bipartisan climate resilience, but new policies are needed to create durable action

The actions taking place in states and local governments, as well as creative financing being trialed in regions across the U.S., demonstrate that elected officials realize that resilience is too important to be used as a political wedge. The impacts of climate change are undermining traditional pathways to economic mobility, including homeownership, small business creation, and affordability. Because of these impacts, building resilience isn’t just a strategy to reduce risks—it can also be a driver of growth and economic innovation, and contribute to securing a future where more Americans can reach the ladders of opportunity they’ve been promised.

This is not to say that states, municipalities, and regions can advance climate resilience alone. These governments would still benefit from federal laws and policies that clarify objectives, set standards, and incentivize action by providing clear and consistent funding. Moreover, federal support can help guarantee fairness, ensuring that implementation unfolds in response to risks and needs rather than local governance capacity or market trends.

New policies are needed. Future reports in this series will build on the data presented here by exploring the types of policies and innovations that could be scaled to provide federal and state policies that are more durable to political challenges. Importantly, this will include policies that articulate climate resilience not only as a goal in itself, but also as a mechanism to advance broader objectives such as regional economic development, economic mobility, and affordability.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).