It is well known that our current fee-for-service system creates an environment that promotes volume over value and unintentionally exacerbates the delivery of fragmented, costly, and uncoordinated care. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) included a number of delivery system reforms, such as Accountable Care Organizations, bundled payments, and workforce provisions to strengthen foundations in primary care. Unfortunately, a focused effort on payments for specialists was not included even though a significant proportion of medical spending and healthcare utilization is attributed to services delivered by specialists, particularly in the Medicare population [i].

The specialty of medical oncology offers an example of the opportunity for specialty physician payment reform. In the current reimbursement model, physicians receive additional financial incentives through margins on the drugs that they prescribe. This can encourage specialists to administer costlier drugs, even when more cost-effective alternatives exist. Second, a growing trend toward treatment in the hospital outpatient setting rather than a doctor’s office is contributing to high cost and cost growth in oncology [ii]. Moreover, little or no payment is provided to low-cost, high-impact, evidence-based services like patient education, palliative care, pain management, and secondary prevention.

Many groups, including Brookings, the American Society of Clinical Oncology, and others have outlined new models for oncology payment reform that address the shortcomings of current reimbursement models. One promising approach is the patient-centered oncology medical home (PCOMH). This model focuses on care coordination and quality improvement, and it is embedded in the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) criteria for a patient-centered medical home (PCMH), with standards adapted for oncology. By allowing providers to receive a per-member, per-month fee in addition to reimbursement for evaluation and management (E&M) services when attaining certain performance and outcomes benchmarks, this model has reduced emergency room (ER) visits and hospitalizations and enhanced patient self-efficacy to improve quality and decrease overall costs. Private payers have already begun to implement such models and have experienced sustained cost savings over time.

Similar opportunities exist in such specialties as cardiology, surgery, and gastroenterology. Each reform roughly follows a similar framework:

- Identify opportunities for elevating the care of high value, poorly reimbursed services.

- Align financial incentives to address these opportunities.

- Encourage clinically informed and provider-led approaches to adopting changes required to support payment reforms.

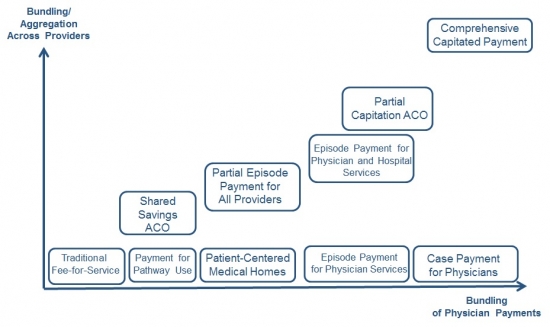

Furthermore, as payment reforms of different types advance in their clinical and financial risk, providers will need to reorganize to match these reforms. The figure illustrates the continuum of aggregation across providers as well as aggregation of payments with comprehensive capitated payments reflecting the most aggregated or bundled form of a payment.

Figure 1:

Model Progression by Case-Based Physician Payment and Bundling/Aggregation Across Providers

Opportunities to enhance value in physician payment are clear, and recent policy trends, including efforts to repeal the Sustainable Growth Rate, are direct evidence that there is a great desire in both the public and private sector to truly bend the cost curve and align financing of healthcare services with the needs of patients and their families.

References

[i] Laugesen M.J., Sherry A.G., 2011. Higher Fees Paid to US Physicians Drive Higher Spending for Physician Services Compared to Other Countries. Health Affairs, 30(9): 1647-1656.

[ii] Fitch K., Pyenson B., 2011. Site of service cost difference for Medicare patients receiving chemotherapy. Milliman, Inc. Commissioned by McKesson Specialty Health on behalf of the US Oncology Network.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edDefining Value for Physician Payment

July 9, 2014