Over the last few years, we have seen a surge in the number of social service models that take a holistic approach to dealing with neighborhood poverty and ill-health. In these models, a central organization often serves as the “hub,” coordinating a range of wraparound services for people in the neighborhood, and tackling simultaneously multiple sources of family distress. The Harlem Children’s Zone, in New York City, is a well-known example of the “hub” approach. Others, such as the Communities in Schools initiative and New York’s Montefiore Medical Center, have adopted similar strategies.

In the best of all possible worlds, initiatives like these would be collecting and using client and services data to know whether they’re working, in both the short-term and with a longer time horizon. But many organizations don’t have the capacity to collect and analyze data, while others, like the Harlem Children’s Zone and the Montefiore Medical Center, desire to better expand and integrate their data. Furthermore, the type of data needed by the organization also differs depending on the stages of development of an organization or program. Unfortunately, while funders are eager to support the services of these organizations, they are generally not investing in the data capabilities to both improve operations and permit rigorous evaluation. And without those data, we diminish the value of the good work the programs are doing—both for the clients served and for funders and others who could learn from the initiatives’ outcomes.

We recently published a case study of one such integrative approach in Washington D.C.: the partnership between Briya Public Charter School, an early childhood and adult education center, and Mary’s Center, a health clinic and social service organization. With a focus on immigrant families, Briya/Mary’s Center combines a two-generation family literacy model in the Briya schools with a sophisticated community health clinic and a range of social services. In two of the program’s sites, the clinic and school even occupy the same building. The partnership employs a multi-pronged approach, which they call the ‘Social Change Model’ that works at the intersection between health care, education, and social services.

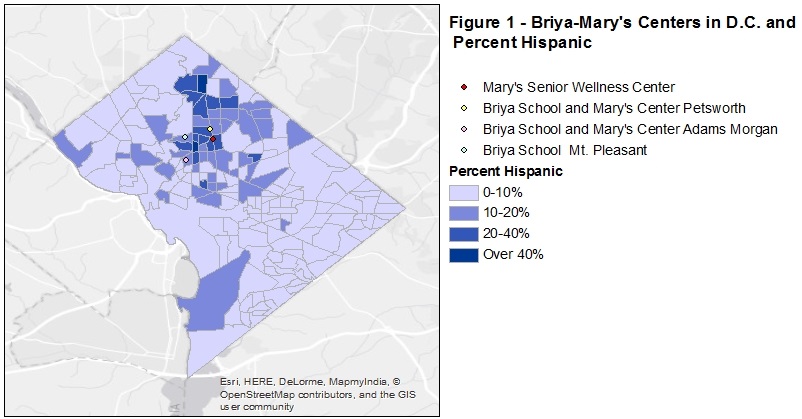

Among its many services, Briya/ Mary’s Center provides adult education and parenting classes, mobile health screening services, teen internships, credentialing services for registered medical assistant and child development associates programs, and college-readiness classes. The schools and clinics are in predominantly Hispanic D.C. neighborhoods (as shown in Figure 1), and Hispanic immigrants make up a large portion of the families served.

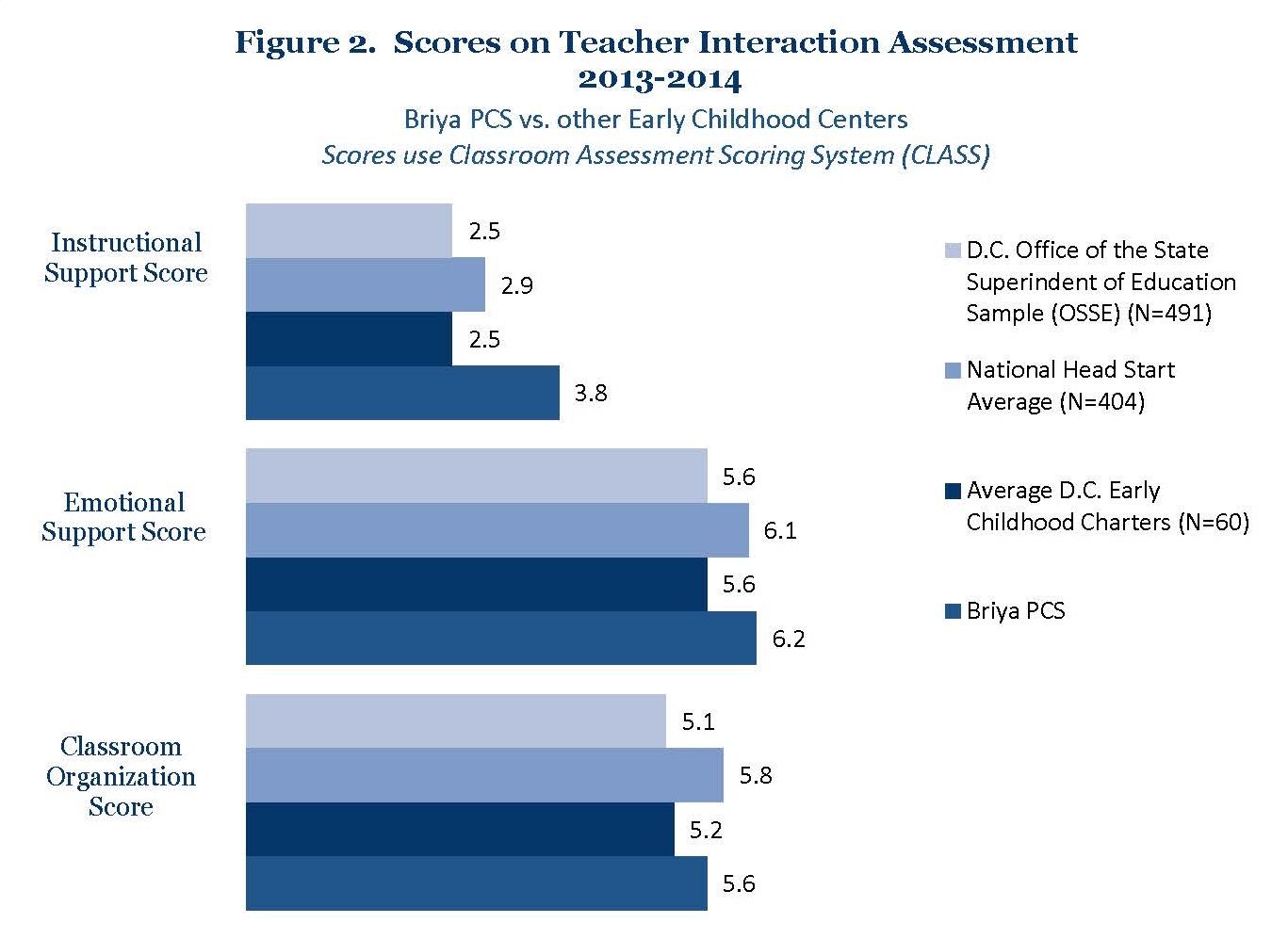

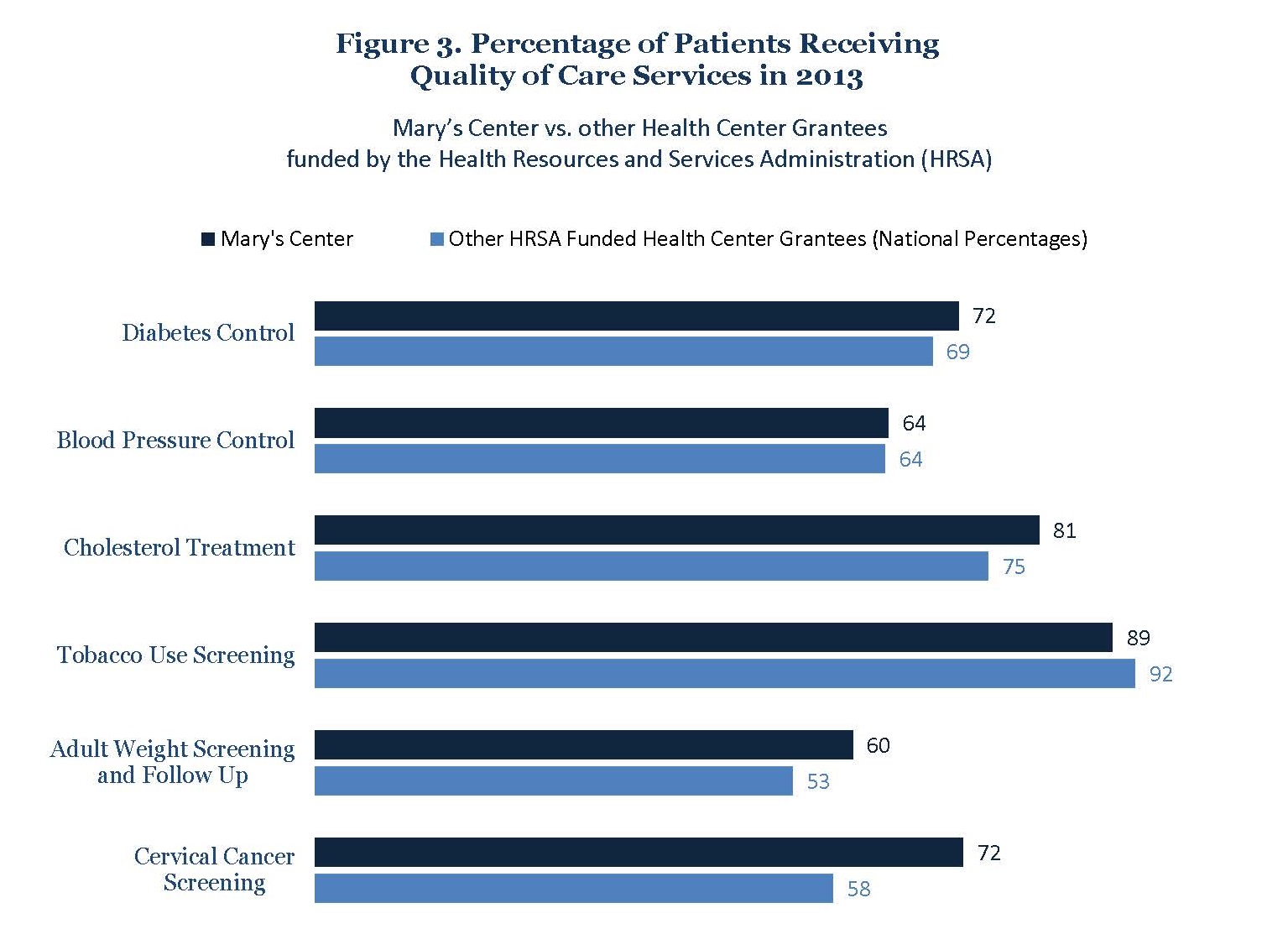

Publicly available performance data on education (Figure 2) and health (Figure 3) strongly suggest that Briya/Mary’s Center is doing as well as or, in most cases, better than its peer institutions on a series of performance and quality measures. Nevertheless, the organization faces at least two challenges when it comes to using evaluation and data to demonstrate its success to municipalities or philanthropists seeking good examples to replicate.

First, it is difficult for organizations like Briya/Mary’s Center to attract financial support to set up the data collection and capabilities needed for evaluation.

Understandably, donors typically prefer to fund services rather than analysis. But adequate data collection, analysis, and empirical evaluation is needed to truly get a sense of the effectiveness of such hubs. Funders need to recognize that unless models are rigorously evaluated, we cannot know for certain whether a program is truly working.

At the same time, we need to be cautious about applying traditional empirical evaluative methodologies to these holistic and innovative hub models. For one thing, the key to these models is their “Inter-connectedness.” Consequently, isolating and measuring the effect of one or a series of interventions using a few outcome variables – as is done under randomized controlled trials and similar methodologies – will not capture the full impact on families exposed to a full set of wraparound services. Moreover, the organizations are evolving as they innovate. So insisting on formal evaluations too early in an organization’s development can freeze change while not producing the data needed to guide operations and improve services.

To address the interconnectedness issue, researchers should use a mixed-methods strategy, incorporating both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, to try and capture as many of the different layers as possible of approaches like Briya/ Mary’s Center. The national 5-year evaluation of the Communities in Schools Model serves as an good example of a research approach that used a multi-layered, mixed-method strategy, incorporating an array of qualitative and quantitative approaches — randomized controlled trials, case studies, teacher surveys, synthetic cohort analysis, etc. — to get an approximation of the effect of these holistic models on their communities.

To address the concern about impeding innovation and change, in the initial stages of new programs funders should invest in performance and data tracking mechanisms to help measure the progress of new initiatives and refine them – without constraining them to the rigid structure of a formal evaluation. Only after the initial, trial-and-error phase, should the focus be on the formal evaluation that’s appropriate for assessing the impact and replicability of the initiative.

Second, obtaining usable long-term individual-level data is difficult.

While Briya/Mary’s Center has an integrated, robust system for keeping track of utilization and performance metrics of the families they serve, they have only limited individual-level data on services their families are exposed to outside of the hub. Nor can they track the experiences of their children and parents after they leave Briya. So they cannot properly compare the longer-term impact of their two-generation model with the effectiveness of other approaches.

One obstacle they face in collecting broader individual-level data is privacy rules, such as HIPAA and FERPA. While such rules provide important safeguards, they can often hamper community-level data sharing. Another is that tracking clients after they leave can be difficult and costly. And in addition, the lack of interoperability of data systems across institutions makes it hard to integrate the data that is available. Fortunately, some data-intermediaries, such as D.C. Health Matters Initiative (which Mary’s Center belongs to) and Neighborhood Info D.C., are beginning to help organizations address this problem by improving access to community-level data and offering strategies to work within existing HIPAA and FERPA laws.

Our examination of Briya/Mary’s Center underscores the importance of funders ensuring that such organizations can create a broad data collection and sharing ecosystem. There needs to be support for hubs to launch data partnerships with the other organizations in the community and to develop data systems for both operational and evaluation purposes. In some cases a hub organization could even serve as the data centralizer for other services the community, consolidating individual-level panel data for the benefit of the whole neighborhood. In that way individual-level data could flow into an organization like Briya/Mary’s Center and then back out into the community. Other neighborhood partnerships and intermediaries, such as those belonging to the Family League of Baltimore or the Strive Network in Cincinnati, might serve as models for building such data-sharing ecosystems in communities.

Figure 1 source: American Community Survey, 5 Year Estimates, 2009-2013. Unit of Analysis: Census Tract.

Figure 2 sources: 2014 Early Childhood Performance Management Framework D.C. PCSB, The State of Pre-K in the District of Columbia 2014 Pre-K Report, Office of Head Start National Overview of Grantee CLASS Scores in 2014.

Figure 3 sources: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Center Data & Reporting, Mary’s Center Data 2013. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Health Center Data & Reporting, National Program Grantee Data 2013.

Editor’s Note: This post originally appeared on The Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco / The Urban Institute What Counts for America Blog

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edData and measurement issues surrounding “hub” models: The case of Briya/Mary’s Center

August 13, 2015