Typically these summary articles open with a statement something like “it’s been an eventful and challenging year”, or something. We will not, hopefully, have to resort to such hyperbole in future years – because in 2020, it has been true. Here in the Center on Children and Families, we continued to develop our work under the Future of the Middle Class Initiative – and there’s lots more to come over the next few months. (Check out in particular our New Contract with the Middle Class, a synthesis of big ideas to help the middle class and featured below.)

But the twin crises of the year, a global pandemic and a national reckoning on racial justice, necessarily become an additional focus for our work – and in particular, the intersection between them. Here then are our most-read articles of the year:

A trope that emerged from the COVID-19 pandemic is that the virus “does not discriminate” and is, in a way, an “equalizer” for society. That message was clearly wrong. In June 2020, the CDC released data for coronavirus related deaths and showed that the death rate is significantly higher for Black and Hispanic/Latino communities. These trends are indicative of racism imbedded throughout the public health system (for example, people of color have a greater prevalence of co-morbidities including hypertension, obesity, diabetes, and lung disease) and persistent inequalities in the workforce (for example, people of color are more likely to be in face-to-face occupations including restaurant service or retail positions). While the CDC data showed alarming racial disparities in the COVID-19 death rate, it concealed the true extent of its impact across racial lines. Tiffany Ford, Sarah Reber, and Richard Reeves explored the data further and found that after correcting for age, the racial gaps in COVID-19 death rates grew even larger. They found that because white people, on average, tend to live longer than people of color and because COVID-19 death rates are higher for older populations, the death rates by race were skewed. A more accurate analysis of COVID-19’s impact can be found by accounting for differences in the age distribution in each racial group. Their results are striking. The crude death rate already indicated large gaps between Black and white populations, but after adjusting for age, the COVID-19 death rate for Blacks increased to 3.6 times that for whites. Clearly, the pandemic has not been an equalizer in any capacity but instead, has disproportionately affected more vulnerable populations—particularly those of color.

Another trend is appearing in the COVID-19 death rate: men are at higher risk of dying from the virus than women. The risk of contracting COVID-19 is similar for both genders yet has a greater mortality risk for men. Global Health 50/50, a nonprofit that highlights health inequalities by sex, is collecting COVID-19 statistics across the globe, and their evidence shows that for every 10 females that die from COVID-19, 14 men are expected to die. This disparity is particularly large in the middle age years: between the ages of 45 and 54, there are about five men dying for every two women. This trend gradually neutralizes for older age groups and it is worth underscoring that more women over the age of 85 have died from the virus, despite having a lower death rate, simply because there are significantly more women in this age group than there are men. This suggests that COVID-19 death data might be concealing the degree of the gender death disparity. In this piece, Tiffany Ford and Richard Reeves explored that question using data from New York City. They found that men are only slightly more likely to contract the virus, but much more likely to be hospitalized and to die. And after adjusting for age, which accounts for the fact that there are fewer men than women in the oldest age groups, the gender gap grows even wider. There is no clear explanation for why this trend occurs. Some researchers are exploring the possibility that men have certain pre-existing conditions or immunological and hormonal differences, but, ultimately, the cause is unknown.

A second trope that emerged at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic is that with more people “stuck” at home, more children will be born in nine months’ time. But this hypothesis seems to ignore the economic perils caused by COVID-19 and how that impacts family planning. Melissa Kearney and Phillip Levine explore this topic and argue that COVID-19 will likely lead to a “baby bust.” With so much economic uncertainty and a tremendous loss of jobs, families are likely not in a position to welcome new children. This trend is not new. In fact, following the economic damage caused by the Great Recession, the birth rate fell 9% between 2007 and 2012, translating to about 400,000 fewer births. Kearney and Levine explored this data further and found that, at the state level, a more extreme economic downturn led to a greater decline in birthrates. Their results suggest that, all else equal, a one percentage-point increase in the unemployment rate is associated with a 1.4 percent decrease in birth rates.

To account for the public health aspect of family planning, they also explored fertility data from the 1918 Spanish Flu. Their research suggests that in each wave of the Spanish Flu, in which death rates increased, there was a simultaneous decrease in birth rates (nine months later). They also note that when death rates returned to normal levels, so did birth rates. There was not a subsequent spike in birth rates to compensate for the period of reduced fertility, suggesting fewer total births. Combining both the economic impact of COVID-19 and the public health effect on families, Kearney and Levine predict that there will be between 300,000 to 500,000 fewer births next year. They further suggest that many of these births will not be delayed but will never happen.

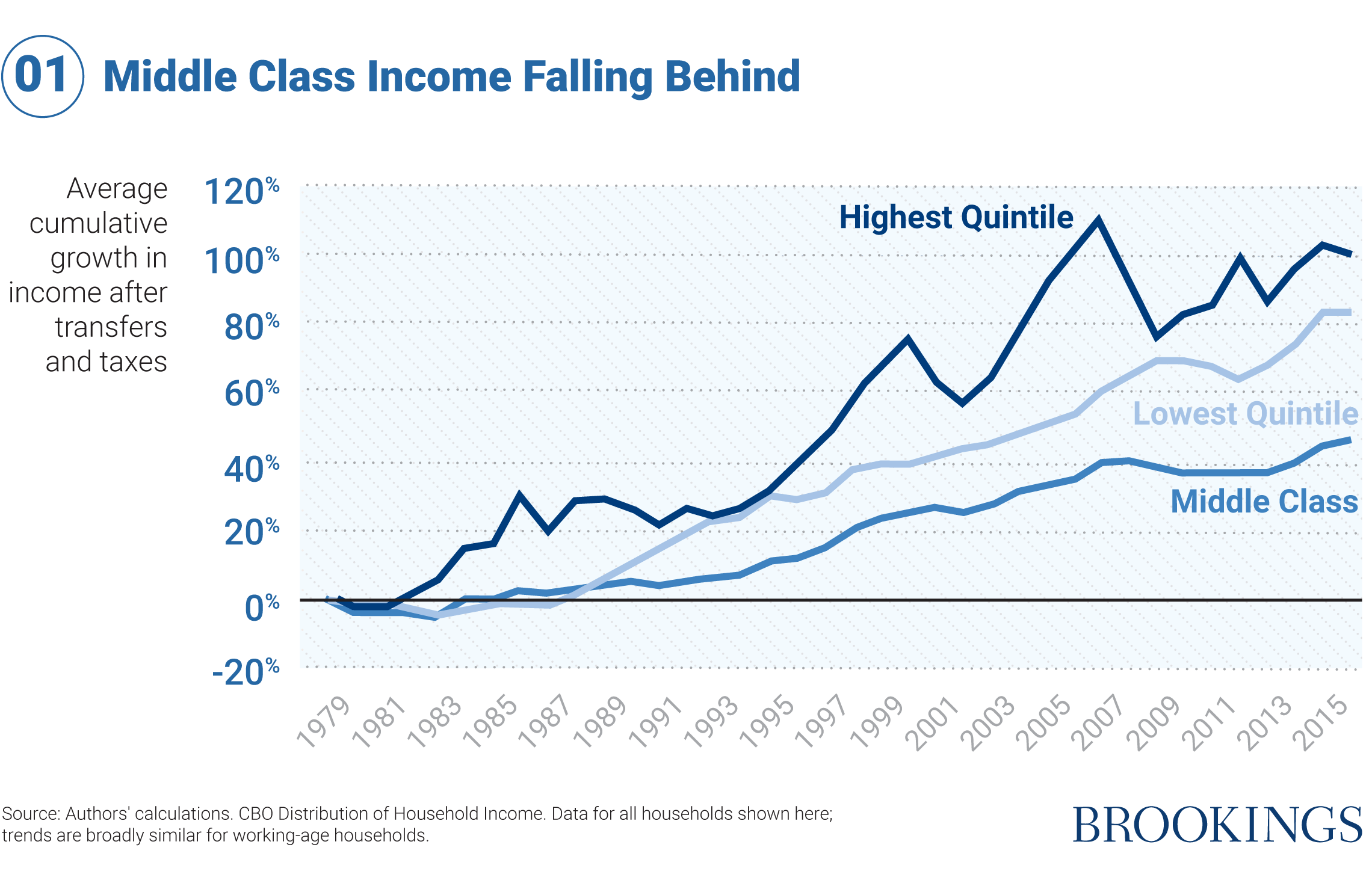

The middle class has always been a defining feature of American life (echoed here by President-elect Joe Biden at the launch of our middle class Initiative), and most Americans will self-identify as being middle class. But the middle class is changing substantially, and the contract that exists between American society and the middle class is beginning to collapse, as argued by Isabel Sawhill and Richard Reeves. In this publication, they explore five core domains for middle class life in America—money, time, relationships, health, and respect—and identify key issues American households are facing. One concerning trend they highlight is the extreme time squeeze placed on American families. Middle-class households are working more hours but have very little to show for it. Those in the highest quintile of earnings and those in the lowest quintile have experienced more growth in income (after transfers and taxes) in the past forty years than the middle class. This growth is largely attributable to more women entering the labor market, and if it weren’t for their economic contributions, middle class incomes would have stagnated. As a result, families now need two earners to make ends meet, placing an extreme squeeze on their time. On average, Americans spend 200 to 400 more hours at work over the course of the year than the average worker in most European countries. They also receive fewer days off and virtually no paid family leave if they welcome a child or get sick. In two of their proposals, Sawhill and Reeves suggest that public policy can better support American middle-class households by eliminating income tax for most of the middle class and providing twenty days of guaranteed paid leave per year for all workers.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a substantial, and rapid, increase in the number of telecommuting workers, and Katherine Guyot and Isabel Sawhill argue that this trend will likely continue post-pandemic. The technology that allows for remote work has been around for many years, but businesses have largely been resistant to investing in the resources and management strategies needed to operate a virtual workforce. COVID-19 has forced them to make the necessary investments and with these new practices already in place, it’s possible that there will be a permanent shift towards telecommuting. However, the ability to work from home is not equally distributed. Data from 2017/18 suggests that 62% of workers in the top quartile of earnings could work for home, but only 9% of workers in the bottom quartile could. This inequality has remained true during the COVID-19 pandemic. In March 2020, Gallup polling revealed that 45% of bottom quintile earners had to stay home from work and were unable to work, while this was only the case for 19% of top quintile earners. Another important piece of addressing unequal distribution is broadband connection. In the past two decades, access to high-speed broadband has increased dramatically, from about 1% in 2000 to 73% in 2019. However, many rural areas in the country have not benefited from this rapid growth, and as much as 14% of urban households are still digitally disconnected. Teleworking may have a promising future but increased investment in broadband service is necessary to ensure that jobs are available in all areas.

In this piece, Richard Reeves and Jonathan Rothwell explore data from Gallup polls on class differentials and associated risks in the pandemic, finding that the less affluent are doubly disadvantaged. First, they are less likely to be able to remain socially distant. For those in the bottom quintile of earnings, 59% were able to avoid going to public places, such as stores or restaurants. This compares to 71% of top quintile earners. Simply put, avoiding large crowds and limiting contact with others is a luxury. High earners are more likely to be able to work from home, have other people shop for them, and stockpile necessary household items.

Second, the rates of diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorders are much higher for low-income communities; bottom quintile earners are three times more likely to have diabetes than top quintile earners. These health risks amplify the impact of the virus and raise mortality rates, making COVID-19 much riskier for low-income communities. In combination with a lack of resources, bottom quintile earners have been doubly disadvantaged during the pandemic.

When the pandemic began in March of 2020, unemployment skyrocketed, the stock market crashed, and millions of families faced economic hardship, with no known end. While this crisis was recognizable around the world, each nation’s response varied. Governments faced competing demands to support businesses and maintain employer-employee relationships, and at the same time, meet the basic needs of people who were struggling to get by. Jonathan Rothwell and Hannah Van Drie explored this topic in-depth by compiling data on unemployment and related benefit claims from twenty wealthy countries.

They found that since March, approximately 11.9% of the workforce—about 58 million workers—across these twenty nations registered as unemployed or received some form of formal assistance. The United States stands out with the highest proportion of its workforce filing for unemployment (at 14.8%), and Germany with the lowest proportion (-0.1%). Their research also found that strict measures to combat the spread of the virus did not necessitate greater economic disruption. For example, Australia and New Zealand stand out for limiting the threat of COVID-19—achieved by impressive testing rates and tracking efforts—while still maintaining low unemployment rates (3.8% and 1.6%, respectively). Ultimately, the ability to balance a robust economic recovery and limiting the spread of COVID-19 varies widely across these countries, and the responses of New Zealand, Australia, Denmark and Germany are worth further examination. The response of the United States, however, which has high unemployment rates and a high number of COVID-19 cases, should not be counted as a success.

A recent proposal to lift the cap on the federal tax deduction for state and local taxes (SALT) has been met with varying reactions, including by the Democratic party where top party members have spoken in favor of removing the cap. Both Sentate Minority leader Chuck Shumer of New York and House Majority leader Nancy Pelosi of San Fransico have argued that a SALT cap repeal would help cushion the impact of the pandemic. But research conducted by Christopher Pulliam and Richard Reeves, using data from the Tax Policy Center, finds that a reduction would disproportionately benefit the wealthy. And at a time of increasing inequality, not least because of the pandemic, it is difficult to justify a handout to the rich. Before the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), taxes paid to state and local governments could be deducted against Federal income taxes. The TCJA capped this benefit at $10,000 a year, reducing the benefit available to high earners living in high-tax cities and states. If this cap were to be repealed, it would be a tax handout to the richest families. Indeed, Pulliam and Reeves find that most of the benefit would go to the top 1%, providing them an average tax cut of nearly $145,000. The middle 60% of the income distribution, on the other hand, would receive an average annual tax reduction of less than $27. (They also opined on this issue in the New York Times, under the headline, “The Tax Cut for the Rich That Democrats Love”).

Another defining moment of 2020 was the tragic murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers and the subsequent wave of protests throughout the country and around the world. Amid a pandemic, citizens left the safety of their own homes to demand substantial, and long-overdue, criminal justice reform. The size and duration of their energy has successfully sparked change across the country, from removing slavery-linked statues to altering police budgets. In this piece, Mary Blankenship and Richard Reeves examine how the movement for racial justice developed online, using Twitter traffic from May 27th to June 4th. They looked at all tweets containing the word “protest” and found that the original focus was primarily on George Floyd, but it quickly expanded to Black Lives Matter. At the same time, the geographical concentration of tweets spread from Minneapolis to New York City, Washington, D.C., and Los Angeles. The energy seen on Twitter and in major cities across the country has sparked a movement for racial justice and will hopefully continue to translate into meaningful policy change.

In the fall of last year, the Future of the Middle Class Initiative launched the American Middle Class Hopes and Anxieties Study (AMCHAS) to get a sense of how middle-class Americans view their lives. Participants in cities across the country were asked questions across five core domains: money, time, relationships, health, and respect. The focus groups were assembled before COVID-19 and follow-up interviews were conducted, via Zoom, during the pandemic. This allowed the researchers to understand what life was like before and during a twin health and economic crisis. Jennifer Silva, Isabel Sawhill, Morgan Welch and Tiffany Ford found that American middle class households, even before COVID-19, were “teetering on the edge” of financial disaster and anxiously anticipating an emergency that would set them back. By April 2020, some participants had been laid off from their jobs and were struggling to make ends meet. For others, COVID-19 provided a brief respite from rising rents, the threat of eviction, or student debt repayments. Some participants even revealed that, given stay-at-home orders, they had more free time in their normally hectic lives. Of course, this is true for some more than others. Many women shared that stay-at-home orders resulted in an impossible demand of balancing childcare and household duties, while also working full- or part-time. This study reveals the intense, yet often taken-for-granted, pressures and vulnerabilities of the middle class both during and before the pandemic. Hearing participants speak about their lives provides a better sense of the sheer unworkability of middle-class schedules and budgets in more “normal” times. Perhaps the COVID-19 pandemic will be an opportunity for reflection and ultimately, structural change.

It is clear that the economic, educational and social disruptions of 2020 pose a deep challenge to equity – a challenge that will to be faced not only in 2021, but for years to come. But these challenges are not new. The call to improve economic opportunity and racial equity in our nation was pressing before 2020; now it feels unanswerable.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

COVID-19, economic mobility, racial justice, and the middle class

Our top 10 of 2020

December 21, 2020