As that great legislative strategist Yogi Berra might ask, “Is it déjà vu all over again?” Could a consumer revolt against cable television rates before the 1992 election replay with digital data in the upcoming election cycle?

Representative Marsha Blackburn (R-TN), chair of the of the House Energy and Commerce Committee’s Subcommittee on Communications and Technology, earlier this year introduced a bill that requires internet service providers to get opt-in consent from consumers before sharing sensitive personal information, and allow opt-out of sharing other information.

Coming from Representative Blackburn, a noted conservative, vocal opponent of government regulation, and early supporter of President Trump, the BROWSER Act (Balancing the Rights of Web Surfers Equally and Responsibly) turned quite a few heads when it dropped. After all, Blackburn was the prime author of the Congressional Review Act (CRA) resolution that rolled back the privacy rules for ISPs that the FCC adopted pursuant to its net neutrality order, which she denounced as “another example of big government overreach.” A key element of those privacy rules was a requirement that consumers opt into any sharing of their data with third parties. The BROWSER Act effectively would reinstate this opt-in requirement for the ISPs and also extend it to internet “edge providers,” such as Netflix and Hulu, whose services are available via the ISPs.

The surprise is even greater given that Republicans in Congress generally have looked unfavorably on consumer privacy legislation. Various hearings seem to echo the sentiment expressed by Senator Pat Toomey (R-PA), who viewed legislative proposals that expanded online consumer protection with skepticism, asking “what is the harm-? Is there a harm?” The BROWSER Act goes against this deeply-ingrained party predilection.

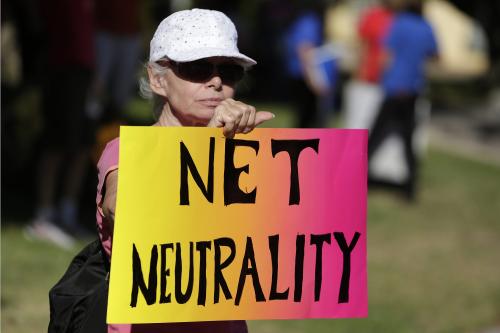

Representative Blackburn’s abrupt and unconventional turn on internet privacy came after widespread public reaction to the congressional repeal of the FCC privacy rules. Former FCC Chairman (and current Brookings visiting fellow) Tom Wheeler, who championed the adoption of the agency’s net neutrality and privacy rules, expressed disapproval in a op-ed piece in The New York Times titled “How the Republicans Sold Your Privacy to Internet Providers.” The notion that the repeal empowered ISPs to sell consumer data to third parties became an internet meme and a tagline for activists’ billboards in Blackburn’s district and others.

The example of cable rate regulation

Both of us have a strong sense of déjà vu looking at the BROWSER Act in the context of today’s turbulent political environment.

Back in 1992, the one and only bill passed despite a veto by President George H. W. Bush was to regulate the rates for basic cable television service. The first President Bush vetoed 44 bills during his single term, and although Congress still was in Democratic hands then, Republicans had the votes to sustain all his vetoes until the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992 came along. That bill passed 308-114 in the House and 74-25 in Senate, with numerous Republican votes.

This singular bipartisan override of a presidential veto happened in October 1992, one month before a national election. It succeeded where other bills failed because cable rates became a consumer issue after the Cable Communications Policy Act of 1984 deregulated cable rates by preempting the state and local authorities from regulating the rates of the cable operators they franchised.

Succeeding years saw a steady and large increase in subscriber rates. For example, the General Accounting Office found that between 1986 and 1991, residential cable rates rose by 61 percent. Easy-to-understand pocketbook data allowed politicians to depict cable operators as consumer villains. Few members of Congress were willing to risk their political careers to defend the operators’ ability to test what rates the market could bear, which is what President Bush effectively asked them to do.

Fast forward to the present. With the CRA rollback and this week’s net neutrality day of action behind us, there remains this abiding question: does the introduction of the BROWSER Act indicate that privacy is gaining momentum as a popular consumer issue for politicians, just as cable rates did in 1992?

Can the past repeat itself?

Those who believe that the bill is not likely to pick up any legislative momentum might argue that general anxiety about digital trails left across the internet does not pack the political punch of rising cable rates that consumers could feel when they balanced their checkbooks each month.

Blackburn’s bill also may be seen as a response to some of the edge providers that were most vocal in their objections to the CRA. Perhaps most critically, what happened in 1992 seems like a galaxy far, far away in 2017. That was in a dramatically different, far less polarized era in congressional politics, when numerous Republicans felt more free to join Democrats in voting to override the Bush veto and more exposed at home if they did not. And now the constant reality-TV drama of the Trump presidency sucks up so much political energy that it is difficult for many issues to break through.

Even so, Congress passing the BROWSER Act or other legislation to protect consumer privacy is not so farfetched. After all, the reaction to congressional action on the FCC privacy rules has been the most significant and focused expression of popular concern about digital privacy yet. Congressional Democrats even spoke of making the CRA action eliminating the FCC’s ISP privacy rules a 2018 campaign issue.

In some measure the public reaction here has been misplaced. Given the constraints of ISPs’ privacy policies and goodwill with customers, the legislation did not create a wide-open market to sell individual data as widely claimed; it also had less to do with privacy as such than it did with congressional objections to the underlying net neutrality policy (which was in place for longer than 60 days, so the Congressional Review Act could not come into play) and concerns about regulatory fragmentation. But any such overreaction is simply an indication of just how sensitive public concerns about such data are becoming.

Outside Washington, DC, a theoretical focus on harm and free markets quickly gives way to concrete concerns about potential privacy intrusions that affect people personally. One of us (Kerry) has written about a proliferation of state laws to address privacy concerns such as drones, data from students, and license plate readers even in Republican-controlled states. That juxtaposition continues: the repeal of the FCC privacy rules has led to a spate of state bills to regulate ISP use of data. And on June 27, the Illinois legislature passed a first-in-the-nation location privacy bill, limiting the collection, use, retention, and disclosure of geolocation data from mobile devices without express consent.

At a recent meeting of the advisory board of the Future of Privacy Forum, a non-profit group on privacy thought leadership made up of corporate, civil society, and academic representatives, both of us were struck by an increased interest in some kind of federal baseline privacy legislation, even from people at companies that have been wary before. This is in part a reaction to the proliferation of state legislation, with the hope that federal law can provide a single substitute and even preempt some state laws. It is also a response to consumer concerns and a recognition that gaps in U.S. sectoral privacy laws feed European perceptions that our online privacy is entirely unregulated. An across-the-board baseline thus could help promote consumer trust and reduce the uncertainty over transatlantic data transfers.

Establishing a baseline of privacy protection

Representative Blackburn’s introduction of the BROWSER Act indicates a desire get out in front of concerns about privacy and reaction to the rollback of FCC privacy rules. The largest newspaper in Representative Blackburn’s home state, The Tennessean, put a positive spin on her bill, giving Blackburn the opportunity to tell constituents that she is fighting for them: “To allow consumers to say, ‘OK, I’m going to choose to give you the right to share certain pieces of my information … but I’m not going to choose to have it shared in other ways, there are things I do not want shared,’ I think individuals have the right to do that.”

It would be a mistake to write off her bill as a cynical gesture. Representative Blackburn has shown an interest in online privacy before. She worked with Peter Welch (D-VT) on a privacy task force of the House Energy and Commerce Committee that produced draft legislation on national data breach notification in 2015 and, even in the context of a 2011 speech that focused on her opposition to FCC rulemaking on net neutrality and an earlier Congressional Review Act bill to roll back any regulation, also brought up privacy. She said then that “[e]very day, more of your activities can be tracked” and, while she thought governments should not determine what information is private, she did see a role for government to “simply assure that the individuals know what activities are followed and easily allow you to protect the activities that you decide are nobody else’s business.”

So far, no Democrats have signed on to the BROWSER Act. Republicans have shown they are quite capable of moving legislation through the House without Democratic votes, however, and they may want to do something about a growing concern, especially if it may get traction as an election issue.

The BROWSER Act provides a starting point for a serious discussion of baseline privacy legislation. It covers only internet services – ISPs and a wide variety of services delivered over the internet including e-commerce, online subscription services, and search – but even this would fill a large and growing gap in the patchwork-quilt of federal sectoral privacy laws. Like the Obama administration’s Consumer Privacy Bill of Rights, it requires clear and conspicuous privacy policies and makes its provisions enforceable by the Federal Trade Commission. Unlike the broad set of principles in the former, the BROWSER Act relies almost entirely on notice-and-consent, which is an important element of privacy protection, but far from enough. Notice-and-consent offers a mostly illusory protection, since the volume and velocity of interactions with internet services means almost no one reads these policies and everyone clicks through reflexively. The bill also does not address the increasing number of connected devices for which notice-and-consent are meaningless, if not impossible. Despite its narrow impact, it contains a very broad preemption of state laws. But at least the BROWSER Act provides a current legislative vehicle to discuss privacy and how best to protect it.

Privacy legislation in the 115th Congress could develop into a bipartisan accomplishment that both Democrats and Republicans could trumpet in their home districts during their re-election campaigns. Rather than veto the law as the first President Bush did, President Trump likely would sign it, with a celebratory photo-op at the White House tweeted out to his more than 33 million followers. Like cable television rates in 1992, privacy could become a test of whose side members of Congress are on.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Could consumer internet privacy legislation show potent populist appeal?

July 13, 2017