The 75th NATO summit held in Washington in July underlined how the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific theaters are connected. The final declaration mentions the People’s Republic of China (PRC) twice, indicating its “stated ambitions and coercive policies continue to challenge our interests, security and values.” It also highlights the deepening relations between Russia and the PRC, which Europe now deems a security threat, thus marking a significant evolution of European attitudes toward the PRC.

Additionally, since 2020, the EU and several member states—France, Germany, and the Netherlands—have published their Indo-Pacific strategies, thus providing a solid base for further collaboration, and increased trans-Atlantic/trans-Pacific engagement. While a stronger European presence is called for in the Indo-Pacific, we are also currently witnessing an eagerness among U.S. partners in Asia to work more with Europeans inside Europe, thus demonstrating two-way linkages across the Atlantic and Pacific.

As the U.S. 2024 election approaches and new developments in U.S. politics upend the race, one issue remains the same: the two candidates, Donald Trump and Kamala Harris, have competing views on U.S. alliances. This difference will come into play in the campaign and will be followed very closely by U.S. allies both in Europe and Asia.

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, came as a shock for NATO and demonstrated the alliance’s relevance in the 21st century. The heightened cooperation between allies and unprecedented coordination with the European Union (EU) came as a welcome surprise. Nevertheless, at a time when the United States believes its pacing challenge is the PRC, it has also sought to increase coordination among NATO and non-NATO allies over this issue, which has generated various reactions, some more positive than others. The idea of a NATO liaison office in Tokyo, for example, was initially shot down by France before it was revived by some European leaders. The controversy around the issue of the office ultimately signals differences among allies on how to be present in the Indo-Pacific and how to respond to the PRC. Therefore, what truly matters now is demonstrating U.S. and European capacity—in a trans-Atlantic setting—to share perspectives on key challenges and difficulties, and to find common solutions, especially at a time when geopolitical rivals are doing their best to drive a wedge between the Western allies.

The turning point of Russia-China cooperation

Between NATO’s founding in 1949 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, NATO underwent three phases: 1) the Cold War, with crises in peaks and drops; 2) the post-Cold War moment with the prospect of a Europe whole and free; and 3) the post-post-Cold War moment, with the rise of an assertive Russia. One could argue that Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine is taking the alliance into a fourth phase with a reinvigorated purpose of defending the Euro-Atlantic space, with the added difficulty of the United States facing a two-peer challenge from Russia and China, taken both separately as well as in their common endeavors.

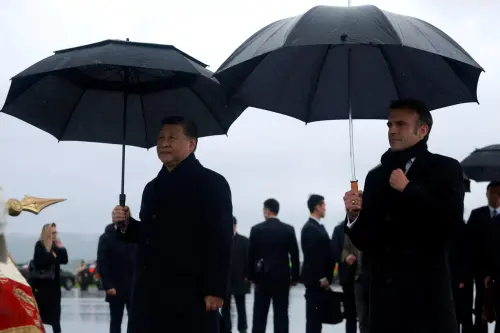

Mere days before the invasion of Ukraine, on February 4, 2022, Xi Jinping and Putin met in Beijing. The two leaders conveyed their desire to counter U.S. influence and argued that no area of cooperation would be off limits. The meeting and the declaration raised alarm bells in Europe and in the United States. Since then, the United States and Europe have warned Beijing of the risks of supporting Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, to no avail. The July 2024 summit in Washington led NATO to call China a “decisive enabler” of Russia’s war in Ukraine, and the allies are weighing the possibility of extending secondary sanctions to Chinese companies in business with Russian companies already under sanctions. It also underlined the “systemic challenges” the Russia-China relationship poses to NATO members. The reference to the “systemic challenges” echoes a formulation the EU uses to refer to its relationship with China, defined as a triptych: the EU and China are partners, competitors, and systemic rivals.

On the eve of the 75th anniversary NATO summit, China and Belarus began an 11-day joint military exercise near the Belarus-Poland border, hence very close to NATO. The military exercise’s timing cannot be coincidental and confirms what Europeans have been reluctant to admit: through its alignment with Russia, China now poses a security threat to Europe.

This newfound European acknowledgment converges with the 2022 U.S. National Defense Strategy’s assertion that “Security architectures in the Euro-Atlantic and Indo-Pacific regions are a critical U.S. strategic advantage over those governments that challenge the rules-based international order.” It should also be noted that China already featured in the 2022 NATO Strategic Concept, which was published just a few months after Russia’s full-scale of Ukraine and uses the same language as the 2024 NATO summit declaration.

Europeans avidly follow the China debate in Washington, attempting to understand how it affects the U.S. commitment to their security, as well as their relationship with China. While some call for a proper geographical division of labor—namely, the United States takes care of Asia, while Europe takes care of its own security—it seems impossible to separate the two theaters, especially in the light of the China-Russia rapprochement. The very idea of a NATO presence in Asia engenders concern on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean. Moreover, should the United States be less engaged in Ukraine, alongside Europeans—who now contribute more military and financial resources to Ukraine than the United States—that would send an adverse signal to Beijing.

The best deterrent to more coercive Chinese action in the Indo-Pacific is a strong United States in Europe. One shouldn’t underestimate the Copernican revolution it took for the European Union—originally, a peace project—to become a security actor providing lethal weapons in Ukraine, a country not (yet) a member of either the EU or NATO. A stronger European pillar in NATO is needed and doesn’t have to come at the expense of the U.S. presence in Europe. The increase in defense budgets across the continent helps both the United States and Europe.

Europe in Asia or Asia in Europe?

All the while, U.S. allies in Asia have been keen supporters of Ukraine in the face of Russia’s aggression. Japan and Ukraine signed a 10-year deal to confirm long-term Japanese support to Kyiv, and Tokyo pledged over $4.5 billion of aid to Ukraine last year. Japan also sanctioned Russia after the invasion began. Likewise, South Korea just announced its intention to double its contributions to the NATO Ukraine Fund to $24 million. In a possible major policy change, South Korea is also considering supplying weapons to Ukraine after Russia and North Korea signed a strategic pact. New Zealand also announced it is increasing its aid contributions to Ukraine, and already froze Russian assets in the framework of the international sanctions regime. Finally, Australia is now promising its biggest increase in aid to Ukraine since the beginning of the war, confirming the strong commitment of the Indo-Pacific 4 (also referred to as IP4) to Ukraine.

Alliances are on the ballot

The issue now is for NATO to do more with the Indo-Pacific, and how the United States will encourage it. In the case of a second Trump administration, allies will be pressured with new demands, though they might differ depending on whether they are European or Asian allies. Trump might also actively try to divide Europeans among themselves, and European and Asian allies. Trump likes to name and shame, so he would openly refer to the contributions of a given country and compare them to those of a fellow ally. For instance, he could complain to NATO allies that Japan and Australia are doing far more to push back against China than Europe. He already put into question the alliance’s credibility when he indicated that he would not defend NATO allies unless they contributed at least 2% of their GDP to defense spending. A similar criticism might fall on Asian allies, whose defense contribution—notably that of Japan—Trump lambasted in the past. His known disdain for alliances also raises concerns regarding U.S. commitments to Taiwan.

In contrast, one would assume a Kamala Harris administration will take an adverse position to Trump’s approach to allies and encourage more partnership and cooperation among allies across the board.

She is ideally positioned to form a bridge connecting the United States’ European and Asian alliances, and to find a commonality of purpose for these in the 21st century: empowering Europeans to spend more on defense, reassuring Asian allies, and getting them to work together on industrial projects, reflecting their common goal of fighting against industrial erosion in all three regions.

She could build on the fact that the IP4 is very interested in understanding how NATO works, even if this new grouping will not extend NATO or replicate it in the Indo-Pacific. The ramifications of how multilateral negotiations work inside NATO, the standardization of industrial norms established by the alliance, the consequences of Russia’s war in Ukraine for the Indo-Pacific, as well as the China-Russia—and North Korea—rapprochement in the cyber, space, and hybrid realms all call for more cooperation.

Defense industrial cooperation is one area where the United States and its European and Indo-Pacific allies and partners can do more together. Execution will be key—the allies should not replicate past oversights such as how AUKUS, the grouping between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, was announced. It will be important to think creatively about fostering new partnerships too: the China discussion can occur in a NATO-EU framework, for example, with the IP4 joining, as the EU is best equipped to tackle resilience, while NATO remains the perfect convening format. Preserving space for multilateral exchanges between the United States, Europe, and Asia is central to the three regions’ strategic objectives, in a year when institutions and alliances are on the ballot too.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Connecting alliances in Asia and Europe

September 16, 2024