Salvador Sánchez Cerén, the former school teacher, ‘comandante’ of guerilla forces and current vice-president of the FMLN, was the clear winner in the February 2 presidential election. With a 10 point lead in the first of two rounds, it will be hard for the rightist party, ARENA to overcome strong preference in Salvador’s rural areas for continued social programs. However, with a weakened and fragmented rightist party, can the FMLN resist following Nicaragua’s path to strengthen presidential power and weaken democratic institutions?

The first round of the Salvadoran presidential elections on February 2 resulted in a 10 point lead for the FMLN candidate, Salvador Sánchez Cerén. Norman Quijano from the ARENA gained the next number of votes, but neither achieved the 50 percent plus one needed to win on the first round. Therefore, both these candidates automatically started their respective campaigns for a second round on March 5. Although a looser on the first round, the former president, Elías Antonio “Tony” Saca from the coalition of center right parties, Movimiento UNIDAD could play a critical role in the second round. His constituents could narrow the gap between the two major parties creating a more competitive election. This paper examines both the political consequences of the presidential election’s first round and analyzes what we might expect in, and beyond the second round on March 9.

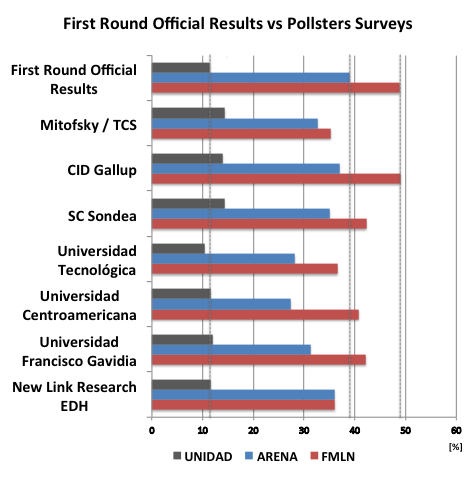

First, the ideological divide between the leftist, FMLN and the business party, ARENA is deep. Since the end of El Salvador’s civil war in 1992, we have not witnessed such a political abyss. Second, Sánchez Cerén will need to demonstrate that Venezuela’s influence and money can be kept at arms length. He may need to enter into a coalition with Tony Saca to assuage fears that the FMLN will not pursue communist or ‘chavista’ policies. (The late Hugo Chavez has given his name to the Bolivarian socialism which characterizes Venezuela, Nicaragua, Bolivia and to a degree, Ecuador.) Third, pollsters are discredited due to their lack of transparency and erroneous predictions. Fourth, the ideological differences between the two major parties are now clearer for the voters. Salvadoran observers have narrowed the choice down to a “socialist” or “free market” system.[1] We might add the choice between a Salvadoran solution to the nation’s problems, or a preference for the Nicaraguan model of a stable economic regime that attracts foreign investment at the cost of weak democratic institutions.

Political polarization:

Norman Quijano of the business party, ARENA focused on the communist background of his opponent, the need for harsher treatment of gang leaders and the formation of “military farms” to intern young people who neither work nor study. These punitive messages failed to resonate with El Salvador’s majority of rural voters, particularly those on the coastal plane which traditionally have supported ARENA candidates. Quijano won 38.96 percent with 1.047 million votes. Observers consider that he ran an old fashioned campaign that failed to persuade voters that poor GDP growth, averaging 1.3 percent growth over the last four years compared to 4.2 percent growth in Nicaragua and low foreign direct investment have not produced the economic development seen in neighboring Central American nations. Quijano gained the majority in the four biggest cities, where a more educated and prosperous population voted, but he failed miserably in the rural areas. This included losses in the Pacific coastal region which has traditionally voted for conservative candidates, including ARENA’s founder Roberto D’Aubuisson. In 2014, ARENA’s base was the educated and more prosperous urban vote.

In contrast, Sánchez Cerén won 48.93 percent with 1.315 million votes. He pointed to the significant reduction in homicides from 14 to five per day without explicitly stating that he supported the March 2012 truce negotiated by the Catholic Church with the gang leaders from the Mara Salvatrucha and the 16th Street. He avoided political debates in which he is the weaker contestant, preferring to engage with citizens at large rallies. All those gatherings were peaceful and despite warnings from ARENA that violence would threaten the presidential campaign, the weeks before and voting day itself were orderly. Salvadorans value representative democracy, but it can be threatened by outside money and a return to political clientelism.

Tony Saca’s Movimiento UNIDAD was a coalition of three center right parties that held together in the hope that Saca’s magnetism could succeed. Until the last few weeks of the campaign, polls had showed a strong following for Saca. On this basis, as well as alleged financial inducements, Saca was able to hold the coalition together during the campaign, but the day after the election UNIDAD fractured. This split among center right parties may be followed by further splintering within ARENA. A dismal campaign, the low turnout of its base and serious headwinds that Norman Quijano faces as he heads into the second round could result in disillusionment among conservatives and a search for alternatives.

Politics in El Salvador are increasingly transactional. Politicians move to wherever the greatest personal benefit is to be found. Small parties emerge around a candidate and follow the leader in the expectation of jobs and positions in the public sector. The Movimiento UNIDAD is a clear example of this. In 2012, members of the National Assembly rebelled against the decision of the Supreme Court’s Constitutional Chamber and preferred to ignore the independence of the judiciary by seeking an interpretation of El Salvador’s constitution at the Inter-American Court of Justice. The issue was whether legislatures could nominate and vote for two sets of Supreme Court justices during one congressional term of office, or whether the constitution restricted them to nominating and voting for one set of justices, each of whom are allied – in a greater or lesser degree – to a political party. Only significant outside pressure obliged the legislatures to compromise and accept the supremacy of Salvador’s highest court on constitutional matters. The political nomination of judges remains a problem in El Salvador, but the relative independence and maximum authority of the Supreme Court was assured for now.

Outside influence and money:

According to a study by the University of Salamanca, ALBA Petróleos has $800 million worth of assets in El Salvador.[2] ALBA Petróleos is funded by the Venezuelan state oil company, PDVSA in a joint venture with 24 Salvadoran mayors from the FMLN. These mayors formed an association, which Spanish acronym is ENEPASA, to enable El Salvador to participate in Venezuela’s PetroCaribe. PDVSA owns 60 percent and ENEPASA; 40 percent of ALBA Petróleos. The purpose is to provide hydrocarbons at subsidized prices and support social programs, such as hospitals, schools, sports and to distribute, at subsidized prices, agricultural products and seeds. According to the Salamanca study, in 2010 ALBA Petróleos distributed $140 million in subsidies and social programs in the 24 municipalities led by FMLN mayors. Salvadoran media covers the distributions widely and picture the close relationship between ALBA Petróleos and the political leaders. Formally, a private joint venture of Salvadoran citizens, few doubt that the Venezuelan government is disinterested in the purpose and use of these monies. In a country whose per annual capital income is $3,799, the targeted distribution of ALBA funds can provide much needed support. They can also re-enforce old fashioned clientelism.

To mitigate the image of a former communist ‘comandante’ presiding over the Salvadoran state, Sánchez Cerén may seek a coalition with Tony Saca, the former president from the conservative party who won 11.44 percent of the vote. However, any coalition with Saca carries perils. Saca is widely rumored to have enriched himself handsomely during his presidency and he has freed his coalition partners to vote as they choose. A fractured party is an unpredictable political force with its members choosing their own personal advantage.

The errors of pollsters:

Pollsters retained by distinct political parties and their allies reinforced the strengths of their clients. In El Salvador, only CID Gallop poll consistently gave the majority to the FMLN candidate. There is likely to be little confidence in pollsters’ predictions as we approach the second round on March 9.

The future of El Salvador’s democratic institutions:

ARENA has little chance to overcome Sánchez Cerén’s 10 point lead. Furthermore, Sánchez Cerén is reputed to be honest, modest and fair. He is trusted as a sincere man of the left. The concern is not for the election of a leftist president because the hemisphere has several notable presidents who lead a “new left” governments that combine liberal free market economies with distributive social policies. Brazil and Peru are good examples. Instead, the concern is for the future of El Salvador’s democracy, built carefully as an integral part of El Salvador’s peace agreement.[3]

Should ARENA and UNIDAD fragment after this politically disastrous first round, which political party will stand to contest the early signs of centralization in the presidency and weakened political institutions? Since the Peace Agreement of January 1992, the FMLN has played by the democratic rules because strong political competition has prevented any one party from eroding the checks and balances of the democratic state. Should the FMLN continue to nominate its candidates to the National Assembly, picking malleable candidates without serious contestation from ARENA, we might anticipate a legislature deprived of the ability to contest the executive.

Already, the federal Electoral Tribunal has failed to constrain President Funes, as a government official, from advocating for a political candidate in violation of El Salvador’s constitution. Funes dominated the airwaves breaching the required balance of radio and TV time for each party. Second, despite the constitutional requirement that the Electoral Tribunal represent the major parties, there is currently no representative from ARENA on this tribunal. (In 2012, ARENA’s man moved to Tony Saca’s party.) Third, to contest the criticism that only 53.8 percent of Salvadorans voted – a relatively low number in comparison with previous elections – the Electoral Tribunal announced four days after the election that the turnout was 64 percent based on the fact that people failed to renew their voter registration thereby reducing the number of those eligible to vote. The Tribunal chose to ignore the hypothesis that a failure to register indicated a disinterest in participating in the election.

Furthermore, the electoral tribunal failed to restrain ALBA Petróleos actions despite the fact that Section 67 of the electoral law prohibits contributions to political parties from government institutions or businesses owned by a foreign state. PDVSA’s 60 percent interest in ALBA Petróleos makes it a foreign business owned by the Venezuelan government. Section 67 also prohibits contributions from political parties and agencies of a foreign government.

Conclusion:

Funes is not President Daniel Ortega of Nicaragua, but he might admire Ortega’s capacity to transact successful business with the corporate sector and ensure a steady inflow of foreign direct investment to support the buoyant export of agricultural and manufacturing products. Ortega has delivered 4.4 percent GDP growth in 2013 and greater welfare benefits. However, the cost to Nicaragua is the destruction of an independent judiciary, deterioration in the rule of law and the manipulation of the National Assembly to enact laws favored by the President. Nicaragua’s reliance on PetroCaribe has provided vital energy support to the Nicaraguan economy, paid for through its exports to Venezuela. El Salvador’s next president may choose to emulate this pattern should the 2nd round remove effective political competition.

The FMLN have proved to be fierce defenders of El Salvador’s constitution in the 22 years since the Peace Agreements enabled their leaders to drop their guns and enter the political arena. The defense of these democratic institutions has encouraged the U.S. Congress, USAID, the Millenium Challenge Corporation (MCC), the European Union and the IMF to extend significant grants and loans to bolster El Salvador’s free market economy and strengthen its judicial institutions. However, a future weakening of democratic institutions risks lowering U.S support.

The United States government and its Embassy in San Salvador have remained neutral observers, but that does not mean that U.S. observers should turn a blind eye to undemocratic tendencies which would damage El Salvador’s future relations with the United States.

[1] See: http://management.fortune.cnn.com/2014/01/31/el-salvador-grapples-with-an-uncertain-future/.

[2] See: http://www.usal.es/webusal/en/node/36957. This study was done with the collaboration of the Salvadoran think tank, FUSADES.

[3] See Diana Villiers Negroponte, Seeking Peace in El Salvador: the Struggle to Reconstruct a nation at the End of the Cold War, Palgrave Macmillan 2012.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Concerns for Democratic Institutions in El Salvador After FMLN First Round Win

February 14, 2014