The following testimony was submitted to the House of Representatives Subcommittee on National Security, Illicit Finance, and International Financial Institutions on March 23, 2023, for the “Follow the Money: The CCP’s Business Model Fueling the Fentanyl Crisis” hearing.

Dear Chairman Luetkemeyer, Ranking Member Beatty, and Distinguished Members of the Subcommittee on National Security, Illicit Finance, and International Financial Institutions of the Committee on Financial Services:

Thank you for holding this hearing entitled, “Follow the Money: The CCP’s Business Model Fueling the Fentanyl Crisis.” This is an important issue that deserves the attention of the House Financial Services Committee and its Members. I am honored to have this opportunity to submit this testimony as a statement for the record.

I am a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution where I direct The Initiative on Nonstate Armed Actors and co-direct the Africa Security Initiative. Illicit economies, such as the drug trade and wildlife trafficking, organized crime, corruption, and their impacts on U.S. and local security issues around the world are the domain of my work and the subject of several of the books I have written. I have conducted fieldwork on these issues in Latin America, Asia, and Africa. In addition to studying China’s and Mexico’s role in various illegal economies over the past two decades, I have been directing over the past three years a new Brookings workstream on China’s role in illegal economies and Chinese criminal groups around the world.

This testimony draws extensively on two detailed reports I published last year: “China’s Role in the Smuggling of Synthetic Drugs and Precursors” and “China’s Role in Poaching and Wildlife Trafficking in Mexico.”

The Brookings Institution is a U.S. nonprofit organization devoted to independent research and policy solutions. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The testimony that I am submitting represents solely my personal views, and does not reflect the views of Brookings, its other scholars, employees, officers, and/or trustees.

Executive Summary

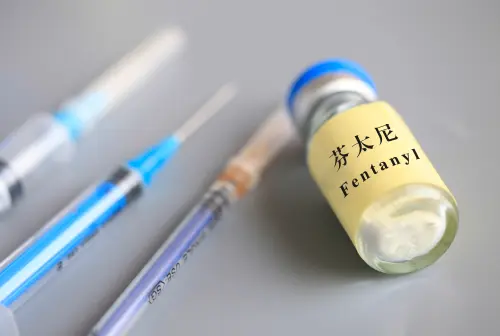

The structural characteristics of synthetic drugs, such as fentanyl, including the ease of developing similar, but not scheduled, synthetic drugs and their new precursors — increasingly a wide array of dual-use chemicals — pose immense structural obstacles to controlling their supply.

U.S. domestic prevention, treatment, harm reduction, and law enforcement measures are fundamental and indispensable to countering the devastating fentanyl crisis.

However, given the extent and lethality of the synthetic opioid epidemic in North America and its likely eventual spread to other parts of the world, even supply control measures with partial and limited effectiveness can save lives and thus need to be designed as smartly and robustly as possible.

Three U.S. presidential administrations — those of Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden — have devoted diplomatic focus to induce and impel China to tighten its regulations vis-à-vis fentanyl-class drugs and their precursor chemicals and to more diligently enforce these regulations. China, however, sees its counternarcotics enforcement, and more broadly its international law enforcement cooperation, as strategic tools that it can instrumentalize to achieve other objectives. Unlike the U.S. Government, which seeks to delink counternarcotics cooperation with China from the overall bilateral geostrategic relationship, China subordinates its counternarcotics cooperation to its geostrategic relations. As the relationship between the two countries deteriorated, China’s willingness to cooperate with the United States declined. Since 2020, China’s cooperation with U.S. counternarcotics efforts, never high, declined substantially. In August 2022, China officially announced that it suspended all counternarcotics and law enforcement cooperation with the United States.

There is little prospect that in the absence of significant warming of the overall U.S.-China bilateral relationship, China will meaningfully intensify its anti-drug cooperation with the United States. U.S. punitive measures, such as sanctions and indictments, are unlikely to change that.

While China takes counternarcotics diplomacy in Southeast Asia and the Pacific very seriously, its operational law enforcement cooperation tends to be highly selective, self-serving, limited, and subordinate to its geopolitical interests. Beijing rarely acts against the top echelons of Chinese criminal syndicates unless they specifically contradict a narrow set of interests of the Chinese Government. Chinese criminal networks provide a variety of services to Chinese legal business enterprises, including those connected to government officials and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

China’s enforcement of precursor and fentanyl analog controls is also complicated by the challenge of systemic corruption in China and the incentive structures within which Chinese officials operate. Chinese Government officials also unofficially extend the umbrella of party protection and government authority to actors who operate in both legal and illegal enterprises as well as to outright criminal groups.

There is little visibility into China’s enforcement of its fentanyl regulations. But in the case of fentanyl and its precursor chemicals, small and middle-level actors in the chemical and pharmaceutical industries also appear to be the key perpetrators of regulatory violations and source for Mexican criminal groups. In the case of fentanyl and its precursors, Chinese triads – mafia-like organized crime groups — do not dominate drug production and trafficking.

Chinese actors have come to play an increasing role in laundering money for Mexican cartels, including the principal distributors of fentanyl to the United States — the Sinaloa Cartel and Cartel Jalisco Nueva Generación (CJNG). Chinese money laundering brokers mostly manage to circumvent the U.S. and Mexican formal banking systems. Other money laundering and value transfers between Mexican and Chinese criminal networks include trade-based laundering, value transfer utilizing wildlife products, such as protected and unprotected marine products and timber, real estate, cryptocurrencies, casinos, and bulk cash.

The increasing payments for drug precursors originating in China in wildlife products coveted there is particularly noteworthy. This method of payment engenders multiple threats to public health and safety, economic sustainability, food security, and global biodiversity. If this wildlife trafficking spreads dangerous zoonotic diseases, it could even pose a threat to national security.

But this convergence of illicit economies also provides the United States with new opportunities for intelligence gathering and law enforcement actions, even as China-Mexico law enforcement cooperation against the trafficking of fentanyl and precursor agents for meth and synthetic opioids remains minimal.

Mexican drug cartels are expanding their role into crimes against nature, and they are also increasingly infiltrating and seeking to dominate a variety of legal economies in Mexico, including fisheries, logging, and agriculture and extorting an even wider array of legal economies. For example, Mexican organized crime groups, especially the Sinaloa Cartel, seek to monopolize both legal and illegal fisheries along the entire vertical supply chain.

There may also be a growing involvement of Chinese fishing ships in facilitating drug trafficking.

And there is the possibility that Chinese fishing flotillas or individual vessels operating around the Americas and around the world may be equipped with spy equipment for collecting intelligence on behalf of China.

Just like with China, Mexico’s cooperation with U.S. counternarcotics efforts is profoundly hollowed out. The March 2023 crisis in U.S.-Mexico law enforcement cooperation is merely the visible tip of the iceberg of how Mexico has eviscerated counternarcotics and law enforcement cooperation with the United States since 2019 and particularly since 2020 when U.S. law enforcement activities in Mexico became shackled and undermined by Mexican Government actions after the U.S. arrest of former Mexican Secretary of Defense Gen. Salvador Cienfuegos.

Because of the diversification of the economic portfolio of Mexican cartels and Chinese criminal networks, to focus primarily on drug seizures close to their source is no longer an adequate approach for effectively countering drug smuggling networks that send pernicious drugs to the United States or their financial systems.

Countering poaching and wildlife trafficking from Mexico and thwarting illegal fishing in Mexican and Latin American waters are increasingly important aspects of countering Mexican drug-trafficking cartels and their damaging effects in the United States and Mexico.

I submit that to attempt to induce better cooperation from China, the United States should:

- continue to emphasize Beijing’s interests in China’s reputation as a global counternarcotics policy leader and leverage multilateral fora to do so;

- continue requesting that China take down websites that illegally sell synthetic opioids to Americans or to Mexican criminal groups;

- strengthen U.S. cooperation with allies and partners to send coordinated messages to push Beijing in preferred directions germane to law enforcement efforts, including greater monitoring and enforcement against sale of precursors chemicals to criminal groups and more robustly and broadly-cast anti-money laundering efforts;

- engage China bilaterally and multilaterally to adopt more robust anti-money laundering standards in its banking and financial systems and trading practices;

- encourage the spread of best practices developed in the China’s pharmaceutical and chemical sectors, including encouraging the industries to adopt self-regulation systems to detect and police suspicious activities, by adopting “know-your-customers” policies, not selling precursors to likely drug traffickers, and alerting law enforcement authorities about such buyers;

- be ready to sanction, including through termination of access to U.S. markets, Chinese firms that violate the best practices protocols and take further actions against those indicted by the U.S. Government;

- develop packages of leverage on prominent Chinese pharmaceutical and chemical industry officials;

- continue developing legal indictment portfolios against Chinese traffickers and their companies, and

- incentivize international partners to act seriously against Chinese drug trafficking and criminal networks.

To attempt to induce better cooperation from Mexico, the United States also has new Policy tools to explore.

Designating Mexican cartels as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTOs) would enable intelligence gathering and strike options for the United States military, such as against some fentanyl labs in Mexico. But the number of available strike targets in Mexico would be limited and would not robustly disrupt the criminal groups. Nor would the FTO designation add authorities to the economic sanctions and anti-money laundering and financial intelligence tools that the already-in-place designation of Transnational Criminal Organization (TCO) carries.

Moreover, such unilateral U.S. military actions in Mexico would severely jeopardize relations with our vital trading partner and neighbor and the FTO designation could significantly limit and outright hamper U.S. foreign policy options and measures.

Instead, the United States should:

- consider significantly intensifying border inspections; and

- develop packages of leverage, including indictment portfolios, against Mexican national security and law enforcement officials and politicians who undermine and sabotage rule of law cooperation with the United States.

Importantly, to effectively counter the fentanyl-smuggling actors, the United States should expand and smarten up its own measures against criminal actors, including by:

- truly adopting a whole-of-government approach to countering fentanyl-smuggling entities;

- authorizing a wide range of U.S. Government agencies, including the Departments of State and Defense, to support U.S. law enforcement against Mexican and Chinese criminal actors and fentanyl trafficking and crimes against nature;

- collecting relevant intelligence on crimes against nature to understand criminal linkages to foreign governments and criminal groups and elevate such intelligence collection in the U.S. National Intelligence Priorities Framework;

- expanding the number and frequency of participation of U.S. wildlife investigators and special agents in Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces (OCDETF);

- increasing the number of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service special agents and investigators, flatlined since the 1970s even as the value of wildlife trafficking has significantly increased since then; and

- designating wildlife trafficking as a predicate offense for wiretap authorization.

Key Aspects of China’s Role as Source of Fentanyl and Fentanyl Precursors

Synthetic opioids are the source of the deadliest and unabating U.S. drug epidemic ever. Since 1999, drug overdoses have killed over 1 million Americans,1 a lethality rate that has increased significantly since 2012 when synthetic opioids from China began supplying the U.S. demand for illicit opioids. In 2021, the number of fatalities was 106,699;2 and in 2022, it is estimated at 107,477.3 Most of the deaths are due to fentanyl, consumed on its own or mixed into fake prescription pills, heroin, and increasingly methamphetamine and cocaine.

Since the Barack Obama administration, the United States has devoted significant diplomatic capital to get China to tighten its regulations vis-à-vis fentanyl-class drugs and to more diligently enforce these regulations.

After years of intense U.S. diplomacy, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced at the December 2018 G-20 summit that China would place the entire class of synthetic opioids on a regulatory schedule.4 According to former and current U.S. Government officials and international drug policy and China experts, the U.S. request that China schedule an entire class of drugs that had precipitated the announcement was a significant ask within the U.S.-China bilateral relationship.5 China had to pass new laws to be able to do so.6

The United States is the only other major country that has controlled the entire class of fentanyl drugs — in the U.S. case, only on a temporary basis, a decision that the U.S. Congress has yet to make permanent.7

But even though China placed the entire class of fentanyl-type drugs and two key precursors under a controlled regulatory regime in May 2019, it remains the principal (if indirect) source of U.S. fentanyl. Fentanyl scheduling and China’s adoption of stricter mail monitoring has created some deterrence effects. Instead of finished fentanyl being shipped directly to the United States, most smuggling now takes place via Mexico. Mexican criminal groups source fentanyl, fentanyl precursors, and increasingly pre-precursors from China, and then traffic finished fentanyl from Mexico to the United States. Scheduling of fentanyl and its precursors in China is not sufficient to stem fentanyl flows to the United States.

China sees counternarcotics and more broadly international law enforcement cooperation as strategic tool that it can leverage to achieve other objectives. As Beijing’s hopes for prospects of improvements in U.S.-China relations have declined, so too has China’s willingness to coordinate with Washington on counternarcotics objectives.

The United States blames China for poor domestic enforcement of its regulations, inadequate actions against Chinese drug smugglers and money launderers, and insufficient regulatory oversight of its non-scheduled chemicals. Highlighting that it does not have any fentanyl abuse problem and thus that its regulatory actions are motivated purely to help the United States, China rejects Washington’s claims and blames the opioid epidemic solely on America’s internal failings. The extent of counternarcotics cooperation — or its absence — remains determined by the state of the U.S.-China overall geopolitical relationship, which has deteriorated over the past decade and shows few prospects for improvement. Thus, the hope that despite the geopolitical rivalry, counternarcotics could prove a domain of U.S.-China cooperation has not yet materialized.

There is little visibility into China’s enforcement of its fentanyl regulations, but China’s enforcement likely remains limited. U.S.-China counternarcotics cooperation remains fraught, and from the U.S. perspective deeply inadequate. Rejecting U.S. blame of China for the opioid epidemic and emphasizing U.S. responsibilities for that calamity, Beijing used to point to its “benevolence” in anti-drug cooperation.8 However, China’s willingness to act on U.S.-provided intelligence to counter Chinese fentanyl- and fentanyl-precursor smuggling rings has been long limited and has significantly tapered off since 2019.

The enforcement of precursor and fentanyl analog controls is also complicated by with the challenge of systemic corruption in China and the incentive structures within which Chinese officials operate. Even with President Xi’s intensive anti-corruption efforts,9 designed mainly to consolidate his own power, eliminate independent sources of influence, and improve the image of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), many mid-level and senior CCP officials remain rent-seeking, with their bureaucratic and power advancement still linked principally to job creation and economic growth in their jurisdictions, even if those objectives are accomplished through means that are illegal or problematic.10 Given the political power of China’s chemical and pharmaceutical industries and the extent of tax revenue and jobs they generate, many Chinese officials are reluctant to monitor, investigate, prosecute, or otherwise cross significant industry players. Small and middle-level actors are more likely to become targets if and when enforcement action is taken.

But in the case of fentanyl and its precursor chemicals, small and middle-level actors in the chemical and pharmaceutical industries also appear to be the key perpetrators of regulatory violations and source for Mexican criminal groups. Moreover, given that fentanyl is a very small source of earnings for China’s chemical industry, powerful Chinese industry actors have little interest in protecting fentanyl and fentanyl precursor production, beyond simply seeking to minimize any oversight into their production and business practices.

Informally, Chinese Government officials have long become accustomed to unofficially extending the umbrella of party protection and government authority to actors who operate in both legal and illegal enterprises as well as to outright criminal groups.11 The frequent appointments of former party officials to business boards could facilitate monitoring and oversight, but frequently enables this unofficial protection and facilitates corruption. However, this clear pattern of behavior is not centrally organized, systemically endorsed, or openly tolerated behavior. It has also been weakened by Xi’s post-2012 anti-corruption drives.12 Even so, a seemingly very dominant and all-powerful state is riddled with “bureaucratic slack,” enforcement inefficiencies, and a proclivity to seek legal and bureaucratic loopholes. Moreover, different provinces often develop distinct forms of illegal bureaucratic protection, complicating uniform, systemic, and efficient application of rule of law.13

Overall, as with other countries such as Australia, China subordinates its counternarcotics cooperation to the geostrategic relationship with the United States. As the relationship between the two countries deteriorated, China’s willingness to cooperate with the United States declined. There is little prospect that in the absence of significant warming of the overall U.S.-China bilateral relationship, China would significantly intensify its anti-drug cooperation with the United States. U.S. punitive measures, such as sanctions and drug indictments, are unlikely to change that.

The evolution of China’s posture toward illicit methamphetamine production in China and the trafficking of meth precursors from China provides important insights into the patterns and limitations of China’s international law enforcement cooperation. As with fentanyl precursors, China emphasizes that it cannot act against nonscheduled substances.

China takes counternarcotics diplomacy in Southeast Asia and the Pacific very seriously, but its operational law enforcement cooperation tends to be highly selective, self-serving, limited, and subordinated to its geopolitical interests.

Nonetheless, after years of refuting international criticism for its role in methamphetamine precursor smuggling amid burgeoning meth production in Asia, China has intensified its regional law enforcement cooperation at least with some countries. It has also mounted stronger internal regulatory measures even for nonscheduled drugs and has undertaken monitoring and interdiction operations.

Yet Beijing rarely acts against the top echelons of Chinese criminal syndicates unless they specifically contradict a narrow set of interests of the Chinese Government. Chinese criminal groups cultivate political capital with Chinese authorities and government officials abroad by also promoting China’s political, strategic, and economic interests.

The intermeshing and mergers between Chinese legal and illegal economic enterprises across the Southeast Asia significantly takes places in Special Economic Zones in Southeast Asia, such as the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone (SEZ) in northern Laos near the border with Myanmar and Thailand. Various U.S. and regional law enforcement officials and international drug policy experts believe that the presence of Chinese and regional organized crime groups in the many of the Mekong region’s at least 74 SEZs14 is large and that the SEZs feature extensive illegal economies, such as drug, wildlife, and human trafficking.15 Yet it does not appear that the Chinese Government has exhibited interest in cooperating with authorities in those countries in sharing intelligence or acting against Chinese nationals in China implicated in likely criminality in the SEZs.16

Nonetheless, in the case of fentanyl and its precursors, Chinese triads — mafia-like organized crime groups — do not dominate drug production and trafficking. The trafficking of fentanyl and its precursors is conducted by a wide panoply of Chinese criminal actors, from small family-based and specialized groups to businesses that also conduct highly diverse legal trade with organized crime groups. Fentanyl and fentanyl-precursor trafficking from China does exist in stark contrast to methamphetamine trafficking in the Asia-Pacific region which is thoroughly controlled and dominated by the Chinese triads.

In the Western Hemisphere, Mexican drug trafficking groups, especially the Sinaloa Cartel and CJNG, dominate the trafficking and wholesale distribution of fentanyl and methamphetamine into the United States. They have become the principal buyers of finished fentanyl from China and India as well as fentanyl precursors and pre-precursors from both countries. Increasingly, the precursor and pre-precursor trade is the method in which the illicit transactions between China and Mexico take place,17 with fentanyl produced from the precursors and pre-precursors in Mexico.

The triads’ franchise-like network organization enhances the groups’ resilience and allows them to absorb considerable financial losses resulting from seizures without bankrupting the groups. The ease of production and smuggling of synthetic drugs further enhance this resilience.

Many of the Chinese smuggling networks are connected in complex ways to legal Chinese businesses. Indeed, the growth of their power in the second half of the 20th century is deeply connected to the growth of China’s legal economy from the late 1970s onward. After their destruction during Mao’s era, the triads in southern China resurrected themselves on the coattails of the growth of China’s legal economy and businesses. But as an expert of Chinese organized crime groups put it, “it is really the synthetic drugs revolution that brought bags of money back to the triads and put a spring into their step.”18

The triads’ connections to China’s legal economy and enterprises remain significant and essential. Like many criminal groups around the world, the triads use legal businesses as fronts for their illegal operations and money-laundering, and they plug into the infrastructure and transportation networks of legal businesses. But they also provide a variety of services to Chinese legal business enterprises, including those connected to government officials and the CCP, such as in the promotion and facilitation of Chinese businesses abroad, the building up of networks of political influence for China abroad, and the informal information gathering and enforcement against Chinese fugitives and Chinese diaspora outside of China, such as to prevent criticism of the regime.

China-Mexico law enforcement cooperation against the trafficking of fentanyl and precursor agents for meth and synthetic opioids remains minimal. As with the United States, China rejects co-responsibility and emphasizes that controls and enforcement are matters for Mexico’s own customs authorities and other Mexican law enforcement to address. China has maintained this posture even as the presence of Chinese criminal actors in Mexico, including in money laundering and illicit value transfers (which increasingly feature barter of wildlife products for synthetic drug precursors) are expanding rapidly.

Money Laundering by Chinese Actors and Value Transfer through Wildlife Trade and Trafficking

Chinese actors have come to play an increasing role in laundering money for Mexican cartels and criminal groups across Latin America (as well as Europe) by using Chinese businesses located in Mexico, the United States, and China, and Chinese informal money transfer systems.19 These informal systems emerged in an effort to avoid banking fees and scrutiny and China’s capital flight controls: China’s laws allow Chinese citizens to move only $50,000 from China abroad per year.

Drug trafficking groups, including in Latin America, are in turn flush with vast sums of hard cash, such as euros and dollars, sought after in China. The National Drug Intelligence Center of the U.S. Department of Justice estimated in 2008 that Mexican and Colombian drug trafficking groups earned between $18 billion and $39 billion a year from wholesale drug sales.20 In 2010, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) estimated bulk cash smuggling to Mexico at between $19 billion and $29 billion annually.21 Other estimates from the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, research organizations, and news media have assessed Mexico’s drug export revenues to have been in the range of $6 billion to $21 billion a year between 2010 and 2018.22

Although it is not clear what percentage of the cartels’ illicit profits is laundered through Chinese money transfer networks, U.S. officials fear that the effectiveness of the Chinese networks’ money laundering is such that it is even displacing established Mexican and Colombian money launderers and putting the flows of cartel money even more out of reach of U.S. law enforcement.23 Chinese operators heavily tax Chinese citizens eager to get money out of China, and are thus able to tax the drug cartels lightly and undercut other money launderers.24 In some cases, a particular Chinese money laundering network managed to get itself hired by both the Sinaloa Cartel and the CJNG; in other cases, they worked exclusively with just one of them.25

As described in detail in Drazen Jorgic’s Reuters special report,26the Chinese brokers mostly manage to bypass the U.S. and Mexican formal banking systems, thus evading anti-money laundering measures and simplifying one of the biggest challenges for the cartels, namely moving large amount of bulk money subject to law enforcement detection. The only interface with the formal banking system takes place in China, into which U.S. law enforcement agencies have little-to-no visibility. Using encrypted platforms, burner phones, and codes, cartel representatives hand over bulk cash to Chinese contacts. The contact brings the money to U.S.-based Chinese businesses with bank accounts in China, and via a phone app from that account transfer the yuan equivalent to other accounts in China, bypassing U.S. bank fees and scrutiny. Chinese money launderers then perform similar “mirror transactions” to convert the money into pesos, utilizing Chinese businesses with Mexican bank accounts.

U.S. investigations and court cases revealed that the Bank of China was among the Chinese financial firms utilized by Chinese operators to launder the money of Mexican cartels.27 In the investigations of the role of Chinese money laundering networks for Mexican cartels, U.S. officials have often been frustrated with the lack of cooperation from Chinese officials. Chinese officials have, however, emphasized that China is ready and willing to “destroy drug cartels and drug-related money laundering networks” and cooperate with the U.S. on the “principle of respecting each other’s laws, equality, and mutual benefit,” adding that the U.S. anti-money laundering requests focused on “legitimate enterprises and individuals” in China without the United States providing evidence of their criminal and drug involvement.28Other money laundering and value transfers between Mexican and Chinese criminal networks include trade-based laundering, value transfer utilizing wildlife products, such as protected and unprotected marine products and timber, real estate, cryptocurrencies, casinos, and bulk cash — though it is not clear what percentage of laundering any of these methods account for.29 An example of trade-based laundering includes Chinese launderers for CJNG buying shoes in China and reselling them in Mexico to give the cartel the necessary cash.30 The casino laundering takes place in ways similar to the informal money transfers: Bulk cash is brought to a casino in Vancouver, for example, where the cartel-linked individual loses it while his money laundering associate in Macau wins and pays the Chinese precursor smuggling networks.31The increasing payments for drug precursors in wildlife products coveted in China — for Traditional Chinese Medicine, aphrodisiacs, other forms of consumption, or as a tool of speculation, such as in the case of the highly prized swim bladder of the endemic and protected Mexican totoaba fish poached for Chinese markets — constitute yet other method of illicit value transfer.32 Other wildlife commodities used for money laundering, tax evasion, and as barter payments between Mexican cartels and Chinese precursor networks include abalone, jellyfish, and lobster.33 Instead of paying in cash, Chinese traffickers are paid in commodities. The amount of value generated by wildlife commodity payments, likely in the tens of millions of dollars, may not cover all of the precursor payment totals, though the latter likely also amount to tens of millions of dollars.34 Wildlife barter may not displace other methods of money laundering and value transfer. But the increasing role of this method can devastate natural ecosystems and biodiversity in Mexico as the cartels steadily seek to legally and illegally harvest more and more of a wider range of animal and plant species to pay for drug precursors.

The connections between the illegal drug trade and the timber and wildlife trade and trafficking from Mexico to China are all the more significant as poaching and wildlife trafficking in Mexico is increasing and Mexican drug cartels are expanding their role in crimes against nature.

They are also increasingly taking over legal economies in Mexico, including logging, fisheries, and various agricultural products such as avocados, citrus, and corn in parts of Mexico.

Wildlife trafficking from Mexico to China receives little international attention, but it is growing, compounding the threats to Mexican biodiversity posed by preexisting poaching for other markets, including the United States. Since Mexican criminal groups often control extensive territories in Mexico which become no-go-zones for government officials and environmental defenders, visibility into the extent of poaching, illegal logging, and wildlife trafficking in Mexico is limited. It is likely, however, that the extent of poaching and trafficking, including to China, is more pervasive and widespread than commonly understood or even considered. Poaching and wildlife trafficking can rapidly deplete this biodiversity.

Terrestrial and marine species, as well as timber, illegally harvested in Mexico for Chinese markets increasingly threaten Mexico’s biodiversity, that accounts for some 12 percent of the world’s biodiversity. Among the species poached in Mexico and smuggled to China, sometimes via the United States, are reptiles, sea cucumbers, totoaba, abalone, sharks, and increasingly also likely jaguars as well as various species of rosewood.

Legal wildlife trade from Mexico to China, such as in sea cucumbers and crocodilian skins, provides cover for laundering poached animals. Illegal fishing accounts for a staggering proportion of Mexico’s fish production, but even the legitimate fishing and export industry provides a means to channel illegally-caught marine products to China.

In Mexico, far more so than in other parts of the world, poaching and wildlife trafficking for Chinese markets is increasingly thickly intermeshed with drug trafficking, money laundering, and value transfer in illicit economies.

Organized crime groups across Mexico, especially the Sinaloa Cartel, seek to monopolize both legal and illegal fisheries along the entire vertical supply chain. Beyond merely demanding a part of the profits, they dictate to legal and illegal fishers how much the fishers can fish, insisting that the fishers sell the harvest only to the criminal groups, and that restaurants, including those catering to international tourists, buy fish only from the criminal groups. Mexican organized crime groups set the prices at which fishers can be compensated and restaurants paid for the cartels’ marine products. The criminal groups also force processing plants to process the fish brought in by the criminal groups and issue it with fake certificates of legal provenance for export into the United States and China. And they charge extortion fees to seafood exporters.

This takeover of the fisheries by Mexican criminal groups puts Chinese traders further into direct contact with them and alters the relationship patterns. Whereas 10 to 15 years half ago, Chinese traders in legal wildlife commodities and illegal wildlife products dealt directly with local hunters, poachers, and fishermen, increasingly Mexican organized crime groups forcibly inserted themselves as middlemen, dictating that producers need to sell to them and that they themselves will sell to the Chinese traders and traffickers who move the product from Mexico’s borders to China.

Mexican criminal groups are also expanding into illegal fishing outside of Mexico. For example, when the overharvesting of sea cucumber in Yucatán, Mexico for markets in China tapered off as a result of the sea cucumber population crash, Mexican organized crime groups that operate in Yucatán started bringing to their seafood collection hubs fish illegally caught in Costa Rica and elsewhere in Latin America.35 Yucatán is also an important hub for cocaine trafficking.

There have long been suspicions about the extent to which Latin American fishing fleets are also engaged in the smuggling of drugs such as cocaine to the United States.36 The penetration of legal fisheries by Mexican cartels further facilitates their drug smuggling enterprise.

Similarly, massive Chinese fishing fleets have long engaged in illegal fishing, sometimes devastating marine resources in other countries’ exclusive economic zones. However, there also appears to be a growing involvement of Chinese fishing ships in drug trafficking, compounding the extensive problem of Chinese cargo vessels carrying contraband such as drugs and their precursors as well as wildlife.37

And there is the possibility that Chinese fishing flotillas or individual vessels operating around the Americas and elsewhere in the world may carry spy equipment collection intelligence for China.

As in illegal logging in Mexico, the interest of Chinese traders in an animal or plant species and efforts to source them in Mexico on a substantial scale for Chinese markets attract the attention of Mexican criminal groups. The Chinese Government, for the most part, rejects China’s responsibility for poaching and wildlife trafficking in Mexico and insists that these problems are rather for the Mexican Government to solve. Prevention and enforcement cooperation has been minimal and sporadic. The Chinese Government has not been keen to formalize either China-Mexico or China-Mexico-United States cooperation against wildlife trafficking, preferring informal case-by-case cooperation.

Nonetheless, under intense international pressure, the Chinese Government moved beyond seizures of the totoaba swim bladder smuggled to China from Mexico and in 2018 mounted several interdiction raids against retail markets. These raids ended the openly-visible and blatant sales of illegal wildlife commodities. Such retail sales moved behind closed doors and onto private online platforms. But it does not appear that China has sustained efforts to counter the now-more hidden illegal retail and has mounted raids against clandestine sales.

Mexican environmental protection regulations and enforcement agencies have been weakened by actions of the Andrés Manuel López Obrador administration, even as Mexican natural resources are increasingly under threat from organized crime and wildlife traffickers. Mexican environmental agencies lack mandates, personnel, and equipment to prevent and stop environmental crime. Government officials, legal traders in wildlife commodities, and even law enforcement agencies in Mexico are systematically corrupted and intimidated by organized crime and the poor rule of law environment facilitates poaching, illegal logging, and wildlife trafficking to China.

Preventing far greater damage to Mexico’s biodiversity from illegal harvesting and poaching and wildlife and timber trafficking requires urgent attention in Mexico with far more dedicated and potent resources, as well as meaningful international cooperation, to identify and dismantle smuggling networks and retail markets.

Importantly, countering poaching and wildlife trafficking from Mexico and acting against illegal fishing off Mexico and around Latin America is increasingly an important element in countering Mexican drug-trafficking cartels. They have diversified their business portfolios into various other forms of illegal trade beyond as well as into legal economies. Primarily focusing on drug seizures close to their source is no longer sufficient to effectively counter their networks or finances.

The Collapse of China’s and Mexico’s Cooperation with U.S. Counternarcotics Efforts

Even for U.S. and international law enforcement and drug policy officials, let alone drug policy experts, there is limited visibility into China’s internal law enforcement actions. This lack of visibility has only intensified since January 2020 when China became the focus of a negative international spotlight due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. As a result, China reduced and even stopped sharing information about how many inspections of pharmaceutical companies it undertook, how many anti-fentanyl and anti-precursor raids it conducted within China, and how many Chinese nationals authorities apprehended or indicted on fentanyl or precursor trafficking charges.38

The most prominent case of prosecution and sentencing of fentanyl traffickers in China resulted in the conviction of nine Chinese nationals for drug trafficking in Hebei province. In 2017, the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) provided their Chinese counterparts with its intelligence that led to the arrests.39 U.S. officials were invited to the sentencing. The case remains perhaps the high mark of U.S.-China counternarcotics cooperation. But it took place when Beijing was still hoping that an improvement in U.S.-China relations was possible and saw counternarcotics cooperation as a mechanism to obtain it. As Beijing’s perception of the likelihood of any improvement in relations has eroded, so too has its willingness to explore coordination on counternarcotics issues.

It does not appear that other high-profile prosecutions have taken place in China since. There also do not appear to be cases of Chinese law enforcement officials prosecuting other individual companies or traders for violations of the May 2019 regulation. However, it is difficult to make assessments of China’s internal law enforcement actions as China has become a black hole for visibility into its internal law enforcement actions.40 That said, after years of U.S. requests, China finally agreed to allow the DEA to open an office in Shanghai, somewhat expanding access for U.S. law enforcement agents in the country.41Worrisomely, since the 2017 collaboration, Beijing has not followed up on other major U.S. indictments of Chinese nationals on drug trafficking charges. Consequently, in August 2019, the U.S. Treasury Department designated the Zheng Cartel, its leader Fujing Zheng, and his father Guanghua Zheng as violators of the Kingpin Act. In July 2020, Treasury added four other cartel operatives and the Global United Biotechnology Inc. (a storefront for the Cartel) to the designation.42 With operations in Mexico and cover companies including veterinary care, computer and other retail, and chemical companies, the cartel has been manufacturing and selling fentanyl and other drugs to the United States and 24 other countries. But Chinese authorities have not moved against the indicted individuals who remain at large.

After the visit of then House Speaker Nancy Pelosi to Taiwan in August 2022, China officially announced that it suspended all of its counternarcotics and law enforcement cooperation with the United States.43

Just like with China, Mexico’s cooperation with U.S. counternarcotics efforts is profoundly hollowed out. In recent weeks, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador has taken to falsely denying that fentanyl is produced in Mexico, deceptive statements echoed at his behest by other high-level Mexican officials and agencies.44 Blaming fentanyl use in the United States on U.S. moral and social decay, including American families not hugging their children enough (the statement an apparent nod to his strategy of confronting Mexican criminals with “hugs and not bullets”), the Mexican President also proceeded to deny that fentanyl is increasingly consumed in Mexico.45 With his statements, President López Obrador is not just unwittingly (or knowingly) echoing China’s rhetoric, but also publicly dismissing two decades of a policy of shared responsibility for drug production, trafficking, and consumption between United States and Mexico.

But this latest crisis is merely the visible tip of the iceberg of how Mexico has eviscerated counternarcotics and law enforcement cooperation with the United States during the López Obrador administration. When President López Obrador assumed office in December 2018, he started systematically weakening that collaboration. From the beginning of his administration, he has sought to withdraw from the Merida Initiative, the U.S.-Mexico security collaboration framework signed during the Felipe Calderón administration. And he sought to redefine the collaboration extremely narrowly as merely U.S. assistance to Mexico in reducing demand for drugs in Mexico while the United States focused on stopping the flow of drug proceeds and weapons to Mexico and reducing demand at home. Previous Mexican governments also certainly sought a significant increase in U.S. law enforcement focus on those two types of illicit flows, but were willing to collaborate also inside Mexico.

After the United States arrested former Mexican Secretary of Defense Gen. Salvador Cienfuegos in October 2020 for cooperation with a vicious Mexican drug cartel, President López Obrador threatened to end all cooperation and expel from Mexico all U.S. law enforcement personnel.46 To avoid that outcome, the Trump administration handed Gen. Cienfuegos over to Mexico where he was rapidly acquitted.

But despite this significant U.S. concession, Mexico’s counternarcotics cooperation remained limited. Meanwhile, U.S. law enforcement activities in Mexico became shackled and undermined by a December 2021 Mexican national security law on foreign agents.47 As a former high-level Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) official Matthew Donahue stated, since then and because of the continually immense level of corruption and cartel infiltration in Mexican security agencies, Mexican law enforcement spends more time surveilling DEA agents than it does cartel members.48

With the threat of Mexico’s unilateral withdrawal from the Merida Initiative, the United States government worked hard to negotiate a new security framework with Mexico — The U.S.-Mexico Bicentennial Framework for Security, Public Health, and Safe Communities49 — in the fall of 2021. The United States emphasized the public health and anti-money-laundering elements of the agreement, as the Mexican government sought. The Framework reiterates multiple dimensions of counternarcotics cooperation, including law enforcement.

In practice, however, the Mexican government actions and cooperations on its side of the U.S.-Mexico border remain profoundly inadequate, including and particularly in law enforcement actions to counter the Mexican criminal groups and their production and trafficking of fentanyl.

The U.S.-Mexico law enforcement cooperation has thus been only limping. The Mexican government has conducted some interdiction operations based on U.S. intelligence, and some collaboration has persisted at the sub-federal level in Mexico. While the DEA operations in Mexico remain hampered and limited, other U.S. law enforcement actors in Mexico have been able to induce some cooperation, with some Mexican government agencies even sharing some intelligence with the United States.

Crucially, as DEA Administrator Anne Milgram stated in her recent Senate testimony,50 the Mexican government continues to be unwilling to share samples and information from its claimed lab busts and fentanyl and fentanyl precursor seizures. It is still not allowing the participation of DEA agents, even in only an observer role, in the interdiction operations it claims it has conducted. Extraditions of indicted drug traffickers to the United States from Mexico also remain limited.

There is no doubt that Mexico’s law enforcement cooperation with the United States has dramatically weakened and is troublingly inadequate.

Conclusions and Policy Implications and Recommendations

As vast numbers of Americans are dying of fentanyl overdose and Chinese and Mexican criminal groups expand their operations around the world and into a vast array of illegal and legal economies, the United States finds itself in hollowed out and weak cooperation with both China and Mexico. Below I offer some policy implications and recommendations on how the United States can attempt to induce China and Mexico to better cooperate with U.S. counternarcotics and law enforcement objectives. I also provide suggestions for what law enforcement and policy measures the United States can undertake independently, and even if Mexico and China continue to reject robust cooperation.

Structural characteristics of synthetic drugs, including the ease of developing similar, but not scheduled synthetic drugs and their new precursors — increasingly a wide array of dual-use chemicals — pose immense structural obstacles to controlling supply, irrespective of political will to prohibit and regulate their use and enforce the regulations. These structural characteristics impose large limitations on supply-side control effectiveness even if China were to radically alter its posture toward counternarcotics cooperation against Chinese drug trafficking networks and start robustly engaging in supply control measures toward synthetic opioids, methamphetamine, and their precursors originating in China with the United States and other countries.

U.S. domestic prevention, treatment, harm reduction, and law enforcement measures remain indispensable and fundamental for countering the devastating fentanyl crisis. It is likely that the most powerful measures to address the opioid crisis are internal policies such as expanded treatment and supervised use.

However, given the extent and lethality of the synthetic opioid epidemic in North America and its likely spread in time to other parts of the world, even supply control measures with partial and limited effectiveness can save lives. That is a worthwhile objective. The Commission on Combatting Illicit Opioid Trafficking stressed that targeted supply reduction and the enforcement of current laws and regulations are essential to disrupting the availability of chemicals needed to manufacture synthetic opioids.51 The Commission also highlighted how improved oversight of large chemical and pharmaceutical sectors and enhanced investigations of vendors or importers in key foreign countries can help disrupt the flow.52 The Report’s supply-side control recommendations include reducing online advertising; encouraging enhanced anti-money laundering efforts in China and Mexico; enhanced interdiction efforts; increased international scheduling of at least synthetic drug precursors that are only used for illicit purposes and enhanced control of precursor flows through collaboration with China and international counternarcotics organizations.53

My recommendations below focus on how to get China to accept such enhanced controls as well as highlight the difficult constraints on shaping China’s behavior toward such desired outcomes.

Yet the effectiveness of all U.S. policy actions vis-à-vis China will be limited by the fact that China subordinates its counternarcotics cooperation with the United States to the overall geopolitical relationships between the two countries and, unlike the United States, refuses to delink it: Without a significant improvement in the geopolitical relationship, there is little prospect of China’s increasing its law enforcement actions against fentanyl and cooperating more robustly with the United States. The greater the rivalry and tensions, the less cooperation China will deliver.

Even so and beyond the direct goal of preventing drug misuse and overdose in the United States and around the world, the United States also has broad global order objectives in its attempt to motivate China to share responsibility for illicit economies in which Chinese actors play a prominent role and for reducing the impunity of Chinese criminal networks, meaningfully sharing intelligence, acting on international indictments, and fostering rule of law at home and abroad.

My recommendations below also analyze and recommend tools to induce Mexico to cooperate more robustly with U.S. law enforcement measures.

U.S. counternarcotics and law enforcement bargaining with Mexico is also constrained by the U.S. reliance on Mexico to stop migrant flows to the United States. If the United States were able to conduct a comprehensive immigration reform that would provide legal work opportunities to those currently seeking protection and opportunities in the United States through unauthorized migration, it would have far better leverage to induce meaningful and robust counternarcotics and law enforcement cooperation with Mexico and would be better able to save U.S. lives. Nonetheless, even absent such reform, the United States can take impactful measures that I discuss below.

Inducing Cooperation from China

With the Chinese government, Washington can continue to emphasize Beijing’s interests in China’s reputation as a global counternarcotics policy leader and leverage multilateral fora such the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime and the International Narcotics Control Board. The United States should also continue to emphasize China’s self-interest in preventing the emergence of a devasting synthetic opioid epidemic in the country as the prescription of opioids in China grows, even though Beijing has thus far been dismissive of these concerns. And Washington should continue requesting that China take down websites that sell synthetic opioids illegally to Americans or to Mexican criminal groups.

The United States should also strengthen its cooperation with allies and partners, such as Australia and Europe, to send coordinated messages to push Beijing in preferred directions of law enforcement efforts, including greater monitoring and enforcement against sales of precursors chemicals to criminal groups and more robust and broadly-cast anti-money laundering efforts. Such coordinated messages will raise reputation costs for China of its law enforcement inactions. There is reason to believe that such coordination among the U.S. and allies as well as regional partners in Asia-Pacific could result in greater Chinese willingness for and diligence in law enforcement collaboration. In other cases where China came to be faced with sustained criticism from countries with which it sought to cultivate influence, such as in Southeast Asian regarding meth precursors or globally regarding ivory trafficking, Beijing has over time altered its stance and adopted more cooperative and accommodating policies.

The United States should continue to engage China bilaterally and multilaterally to adopt more robust anti-money laundering standards in its banking and financial systems and trading practices. Getting China to adopt such more stringent regulatory measures will take considerable time. Meanwhile, China may occasionally be incentivized by the United States to use anti-money laundering measures against particular trafficking networks or chemical companies who are clearly selling precursors to drug traffickers, such as in Mexico. But beyond sporadic actions, there is little likelihood that China will rapidly alter its anti-money laundering stance away from selective focus on Chinese capital flight and toward broader counternarcotics measures. Nor is there high likelihood that any time soon China would allow the U.S. or other countries greater visibility into its banking and financial systems, since it will continue to seek to obfuscate the many problems of both. However, in time, U.S. and multilateral support for China’s implementation of more robust anti-money laundering measures could produce some positive counternarcotics outcomes. There is no evidence to suggest that even stringent anti-money laundering measures would end or significantly reduce the supply of fentanyl to the United States. However, anti-money laundering cooperation could at least help dismantle smuggling networks and perhaps also deter some, thus making it more difficult for the networks to operate. At minimum, it would reduce their ability to operate with wide impunity and to strengthen the enforcement of the rule of law.

With the Chinese government and Chinese pharmaceutical companies, the United States could encourage the spread of best practices developed in the pharmaceutical sector. Over time, Chinese pharmaceutical companies should be encouraged to adopt the full array of global control standards, including the development of better training, certification, and inspection.

Even so, the shift toward precursors and pre-precursors with widespread dual use poses massive structural obstacles to control. The United States should remain deeply engaged in a global discussion on how to develop enhanced special surveillance lists and monitoring and enforcement mechanisms for dual-use chemicals, as those that are not scheduled do not have to be declared in exports.

With no global industry and countries’ willingness to move toward scheduling many dual-use chemicals, the United States should be encouraging the industry to adopt self-regulation systems to detect and police suspicious activities, by adopting know-your-customers policies, not selling precursors to likely drug traffickers, and alerting law enforcement authorities about such buyers.

But even in the banking sector, such post-September 11 know-your-customer, due-diligence policies, and reams of reports of suspicious activities, had limited impact while generating problematic side-effects.54 In comparison with banking, the global chemical industry is far larger and more fragmented, comprised of hundreds of thousands of firms and millions of facilities, including not merely producers but also many brokers. So achieving widespread and diligent adoption of self-regulation and incentivizing it through the punishment of violators is highly challenging. Moreover, in various parts of the world, including China and India, criminal groups have deeply infiltrated the chemical industry,55 making it easy for them to falsify and subvert such self-regulation measures. Reducing criminal infiltration into and corruption within the pharmaceutical sectors in both countries would be necessary to make such measures more effective.

Moreover, these types of public-private partnerships are not common in China and could pose difficulties both for the government and industries. China’s operating practices have largely been that the government writes regulations and the industries implements them (and often seeks to subvert them). And to the extent that many of the unscrupulous sellers of nonscheduled precursors are medium and small firms with smaller legal global market access and thus fewer incentives for compliance, the monitoring and enforcement challenge remains large and resource-intensive.

Firms that violate agreed-upon standards should be put on probation and, if no significant improvement and compliance takes place, should be cut out of the U.S. market and/or indicted by the U.S. government. Washington can insist that Beijing shut down the worst offenders.

Of course, there is a risk that U.S. indictments, or any new U.S. laws mandating that only chemical firms with certain standards can sell to the U.S. market, might stimulate China to retaliate against U.S. businesses seeking access to China’s market — whether by finding reasons to bring criminal investigations against U.S. companies or by organizing social media-led boycotts. China has previously resorted to both.56 Moreover, many unscrupulous sellers are likely to sell their precursors or finished synthetic drugs to drug traffickers abroad, such as the Mexican groups, instead of directly into the United States.

With respect to prominent Chinese pharmaceutical and chemical industry officials, the United States can develop packages of leverage, such as denying them visas if their companies fail to adopt global standards of preventing diversion. Powerful Chinese industry actors may thus be incentivized to promote stricter regulatory standards and their enforcement within China.

But as in the case of U.S. actions against Chinese companies, the Chinese government might retaliate against U.S. individuals and look for ways to charge them with criminal conduct or espionage and arrest them.57 Thus, the implementation of such a sanctioning mechanism would need to be judged very carefully within the broad context of U.S.-China relations.

With respect to Chinese traffickers, the United States should of course continue to develop legal indictment portfolios against them and their companies, even if China will not arrest, prosecute, and extradite them. Because of the poor state of human rights in China, the U.S. should continue to refuse to sign an extradition treaty with China. But Washington can and should deploy other punitive measures, such as limiting traffickers’ access to the international financial system, preventing their international travel, or attempting to have third countries arrest them and extradite them to the United States. Nonetheless, such indictments, particularly if the indicted individuals are linked to the Chinese government or the CCP, may not stimulate China to engage in more extensive counternarcotics cooperation with the United States.

Working with other international partners, the United States could encourage China to start moving more seriously against Chinese drug trafficking networks in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. But as long as these criminal groups also serve China’s economic and internal control interests, such as against Chinese diasporas, Beijing’s willingness to move against them will remain small. Thus, the United States will need to rely on and incentivize other regional partners to vigorously undermine those networks, even as new will emerge in their wake. However, particularly if in the future the replacement networks were not Chinese, the U.S. law enforcement challenges could diminish.

Inducing Cooperation from Mexico

Various U.S. lawmakers have proposed designated Mexican criminal groups as Foreign Terrorist Organizations (FTO).

An FTO designation would enable intelligence gathering and strike options of the United States military, such as against some fentanyl labs in Mexico or visible formations of large Mexican cartels — principally CJNG.

However, such unilateral U.S. military actions in Mexico would severely jeopardize relations with our vital trading partner and neighbor whose society is deeply intertwined with ours through familial connections. Calls for U.S. military strikes against fentanyl-linked targets in Mexico has already been condemned by Mexican government officials, politicians, and commentators.

Meanwhile, the number of available targets in Mexico would be limited. Most Mexican criminal groups do not gather in military-like visible formations. Many fentanyl labs already operate in buildings in populated neighborhoods of towns and cities where strikes would not be possible due to risks to Mexican civilians. Moreover, fentanyl labs would easily be recreated.

Nor would the FTO designation add authorities to the economic sanctions and anti-money laundering and financial intelligence tools that the already-in-place designation of Transnational Criminal Organization (TCO) carries. The latter designation also carries extensive prohibitions against material support.

But an FTO designation could significantly limit and outright hamper U.S. foreign policy options and measures. Clauses against material support for designated terrorist organizations have made it difficult for the United States to implement non-military and non-law-enforcement policy measures in a wide range of countries, such as to provide assistance for legal job creation or reintegration support for even populations that had to endure the rule of brutal terrorist groups. To be in compliance with the material support laws, the United States and other entities must guarantee that none of their financial or material assistance is leaking out, including through coerced extortion, to those designated as FTOs.

Yet such controls would be a significant challenge in Mexico where many people and businesses in legal economies, such as agriculture, fisheries, logging, mining, and retail, have to pay extortion fees to Mexican criminal groups. The attempted controls could undermine the ability to trade with Mexico as many U.S. businesses would not be able to determine whether their Mexican trading or production partner was paying extortion fees to Mexican cartels, and thus guarantee that they were not indirectly in violation of material support clauses.

The FTO designation could hamper the delivery of U.S. training, such as to local police forces or Mexican federal law enforcement agencies, if guarantees could not be established that such counterparts had no infiltration by criminal actors.

Instead, if the López Obrador administration continues to deny meaningful law enforcement cooperation, the United States may have to resort to significantly intensified border inspections, even if they significantly slow down the legal trade and cause substantial damage to Mexican goods, such as agricultural products. Under optimal circumstances, U.S.-Mexico law enforcement cooperation would be robust enough to make legal border crossings fast and efficient. Joint fentanyl and precursor busts and seizures could take place near production labs and at warehouses. The inspections of legal cargo heading to the United States could take place close to production and loading site in Mexico. Under the Merida Initiative, the Obama administration, in fact, sought to develop with Mexico such systems of legal cargo inspection inside Mexico and away from the border. But if Mexico refuses to act as a reliable law enforcement partner to counter the greatest drug epidemic in North America, which is also decimating lives in Mexico, the United States may have to focus much intensified inspections at the border, despite the economic pains.

Packages of leverage, including indictment portfolios, could also be developed against Mexican national security and law enforcement officials and politicians who undermine and sabotage rule of law cooperation with the United States.

Expanding and Smartening Up U.S. Measures against Criminal Actors

Importantly, the United States has significant opportunities rapidly to strengthen and smarten up its own measures against Chinese and Mexican criminal actors participating in fentanyl and other drug trafficking while simultaneously also enhancing U.S. measures to counter wildlife trafficking and protect public health and global biodiversity.

Mexican drug cartels have diversified their activities into a wide array of illicit and licit commodities. Similarly, some Chinese actors smuggling fentanyl are also involved in wildlife trade and trafficking. Some are connecting to the CCP and Chinese government officials. Corruption networks permeate all levels of the Mexican government.

Primarily focusing on drug seizures close to source is no longer sufficient for effectively disrupting fentanyl smuggling and criminal networks implicated in it.

Rather, countering poaching and wildlife trafficking from Mexico and illegal logging and mining in places where the Mexican cartels have a reach, acting against illegal fishing off Mexico and around Latin America and elsewhere, and shutting down wildlife trafficking networks into China are increasingly an important element of countering Mexican and Chinese drug-trafficking groups and reducing the flow of fentanyl to the United States.

To effectively counter fentanyl-smuggling actors requires a whole-of-government approach — not simply on paper, but truly in implementation. A wide range of U.S. government agencies should be authorized to support U.S. law enforcement against Mexican and Chinese criminal actors, fentanyl trafficking, and crimes against nature. These include U.S. intelligence agencies, the Department of State, the Department of Defense, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS).

Moreover, the focused collection, analysis, and reporting of intelligence by a variety of U.S. government actors against wildlife trafficking, illegal fishing, and illegal mining could beget new opportunities to understand the criminal linkages to foreign governments, including China’s, to confirm or dismiss concerns as to whether Chinese fishing vessels carry spy equipment, and to identify the crucial vulnerabilities of Mexican and other dangerous cartels.

To such end, crimes against nature should be elevated as a Collection and Reporting priority of the U.S. Intelligence Community, and within the U.S. National Priorities Framework.

Stove-piping in information and intelligence gathering across a wide set of illicit economies should be ended. Gathered information and intelligence should be shared with interagency analysis groups intent upon interdicting the illicit international flow of scheduled drugs and endangered species. Such efforts could be enabled by increasing the number of USFWS special agents and by augmenting their respective participation in interagency Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Forces (OCDETF) investigations.

The relevant intelligence on crimes against nature to understand and dismantle criminal networks could include names, phone number, license plates, courier accounts, bank accounts, and wiretapped conversations. Conversely, countering groups perpetrating crimes against nature could be productive in terms of freezing accounts and visas to interdict the smuggling of drugs, guns, and humans that they’re conducting.

Enhancing intelligence collection and law enforcement action opportunities stemming from such an expanded lens to cover all of the activities, including crimes against nature, of dangerous and nefarious actors, such as Mexican cartels and Chinese criminal groups, requires enlarging the pool of USFWS special agents and uniformed wildlife inspectors at the U.S.-Mexico border and at transportation hubs within the United States. The DEA appropriately enjoys strong capacities, currently maintaining a force of 4000 agents.58 In contrast, the number of USFWS special agents has for years hovered at a mere and insufficient 220.59 For years, this inadequate number has not increased even though poaching, illegal logging, and mining, and trafficking in natural resource commodities have grown enormously over the past three decades, continue expanding, and increasingly involve Mexican drug cartels as well as Chinese criminal networks.

As a corollary and imperative effort, U.S. law enforcement agencies’ legal authorities to counter wildlife trafficking should be expanded. Importantly, wildlife trafficking should be designated as a predicate offense for wiretap authorizations.60Such expanded authority would bring about multiple benefits: including the enabling, understanding, and demonstration of the connections between wildlife and transnational organized crime networks and foreign bad actors, enhancing the ability to disrupt fentanyl trafficking, and allowing for more expeditious and pointed prosecution of wildlife trafficking crimes. Currently, federal legislation at the foundation of wildlife crime prosecution, at the core of which is the Lacey Act, often entails proof of knowledge on the part of the defendant, a requirement that wiretap authorization would greatly facilitate, in the interest of prosecuting transnational wildlife trafficking and convicting criminal syndicates.

Many fentanyl-trafficking networks are not narrowly specialized in fentanyl or drugs only. Many Mexican cartels and criminal groups no longer solely focus on drug smuggling. Fentanyl smuggling networks have powerful protectors among corrupt government officials worldwide. Incentivizing better cooperation from the Chinese and Mexican criminal governments is important. But particularly given the challenges in inducing such cooperation in the current geopolitical environment and given the policy orientation of the current Mexican government, it is equally crucial to enhance the United States’ own policy tools to counter fentanyl-trafficking networks. Expanding the intelligence-gathering aperture and mandating and resourcing a whole-of-government approach in support of U.S. law enforcement will save U.S. lives currently decimated by fentanyl overdoses.

-

Footnotes

- Julie O’Donnell, Lauren J. Tanz, R. Matt Gladden, Nicole L. Davis, and Jessica Bitting, “Trends in and Characteristics of Drug Overdose Deaths Involving Illicitly Manufactured Fentanyls—United States, 2019–2020,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 70, No. 50, December 17, 2021.

- Merianne Rose Spencer, Arialdi M. Miniño, and Margaret Warner, “Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 2001–2021,” NCHS Data Brief No, 457, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, December 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db457.pdf.

- The White House, Office of National Drug Control Policy, “Dr. Rahul Gupta Releases Statement on CDC’s New Overdose Death Data,” January 11, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/ondcp/briefing-room/2023/01/11/dr-rahul-gupta-releases-statement-on-cdcs-new-overdose-death-data-2/#:~:text=Rahul%2520Gupta%252C%2520Director%2520of%2520the,period%2520ending%2520in%2520August%25202022.

- Mark Landler, “U.S. and China Call Truce in Trade War,” The New York Times, December 1, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/12/01/world/trump-xi-g20-merkel.html.

- Vanda Felbab-Brown’s interviews with eight former and current U.S. officials and international policy and China experts, by virtual platforms, November and December 2021.

- Vanda Felbab-Brown’s interviews with six current and former international drug policy officials, by virtual platforms, November and December 2021.

- Rahul Gupta, Director of the Office of National Drug Control Policy, “Statement for Hearing on Countering Illicit Fentanyl Trafficking,” Foreign Relations Committee United States Senate Wednesday, February 15, 2023, https://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/f4597c23-de04-fa71-e612-bcbc49b6826c/021523_Gupta_Testimony.pdf.

- See, for example, “Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson: The US should look for causes of the abuse of fentanyl from within,” Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the United States of America, December 16, 2021, http://www.china-embassy.org/eng/zmgx/zxxx/202112/t20211217_10470769.htm; “Remarks by spokesperson of the Chinese Embassy in the United States on the fentanyl issue,” Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the United States of America, September 2, 2021, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/ce/ceus//eng/sgxw/t1904232.htm; and “China pushes back at Trump in war of words over opioid flows,” Bloomberg, August 27, 2019, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-08-27/china-pushes-back-at-trump-in-war-of-words-over-opioid-flows; Yusha Zhao, “Ministry urges US to stop slandering China over its own opioid problem,” Global Times, September 3, 2019, https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1163493.shtml; and Yeping Yin, “U.S. blames China for drug trafficking to disguise its own failure: experts,” Global Times, July 22, 2020, https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1195344.shtml.

- See for example Roderic Broadhurst and Peng Wang, “After the Bo Xilai Trial: Does Corruption Threaten China’s Future?” Survival 56, no. 3 (May 2014): 157-178, https://doi.org/10.1080/00396338.2014.920148.

- Vanda Felbab-Brown’s interviews with two international experts on China and two former law enforcement officials who were posted in China, by virtual platforms, December 2021. See also Iza Ding and Michael Thompson-Brussar, “The Anti-Bureaucratic Ghost in China’s Bureaucratic Machine,” The China Quarterly 248, no. S1 (November 2021): 116-140, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741021000977. For an insider’s account of corruption in China, see Desmond Shum, Red Roulette: An Insider’s Story of Wealth, Power, Corruption, and Vengeance in Today’s China (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2021).

- Vanda Felbab-Brown’s interviews with two international experts on China and two former law enforcement officials who were posted in China, by virtual platforms, December 2021

- Peng Wang and Xia Yang, “Bureaucratic Slack in China: The Anti-corruption Campaign and the Decline of Patronage Networks in Developing Local Economies,” The China Quarterly 243 (November 19, 2019): 1-24, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741019001504.

- Vanda Felbab-Brown’s interviews with two international experts on China and two former law enforcement officials who were posted in China, by virtual platforms, December 2021.

- Estimating the number of SEZs in the Mekong region is difficult because of the lack of data and different typologies of “economic zones.” The Heinrich Böll Stiftung and Land Watch Thai estimate that there are at least 74 “special economic zones” at various stages of development in the Mekong region, and that if various different kinds of “economic zones” are included (e.g., industrial zones, industrial estates and parks, coastal economic zones, cross-border special zones, etc.), the number increases to some 500. See Pornpana Kuaycharoen, Luntharima Longcharoen, Phurinat Chotiwan, Kamol Sukin, and Lao independent researchers, “Special Economic Zones and Land Dispossession in the Mekong Region,” (Bangkok: Heinrich Böll Stiftung Southeast Asia and Land Watch Thai, May 24, 2021), https://th.boell.org/en/2021/05/24/special-economic-zones-and-land-dispossession-mekong-region.

- Vanda Felbab-Brown interviews with former and current U.S., Southeast Asian, and Australian law enforcement officials, international drug policy officials, and international experts on drug and wildlife trafficking in Southeast Asia, by virtual platforms, November and December 2021.

- Ibid.

- Vanda Felbab-Brown’s interviews with U.S. and international law enforcement officials, by virtual platforms and in Mexico City, October, November, and December 2021. See also Lauren Greenwood and Kevin Fashola, “Illicit Fentanyl from China and “DEA Intelligence Report: Fentanyl Flow to the United States,” U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.”

- Vanda Felbab-Brown’s interviews with an expert on China’s organized crime groups, by virtual platform, December 2021.

- For background, see John Langdale, “Chinese money laundering in North America,” The European Review of Organised Crime 6, no. 1 (2021): 10-35, https://standinggroups.ecpr.eu/sgoc/wp-content/uploads/sites/51/2021/05/4-Researchnote.pdf.

- “Illicit Finance,” in National Drug Threat Assessment 2009 (Washington, DC: National Drug Intelligence Center, U.S. Department of Justice, December 2008).

- Ibid.