Director’s summary

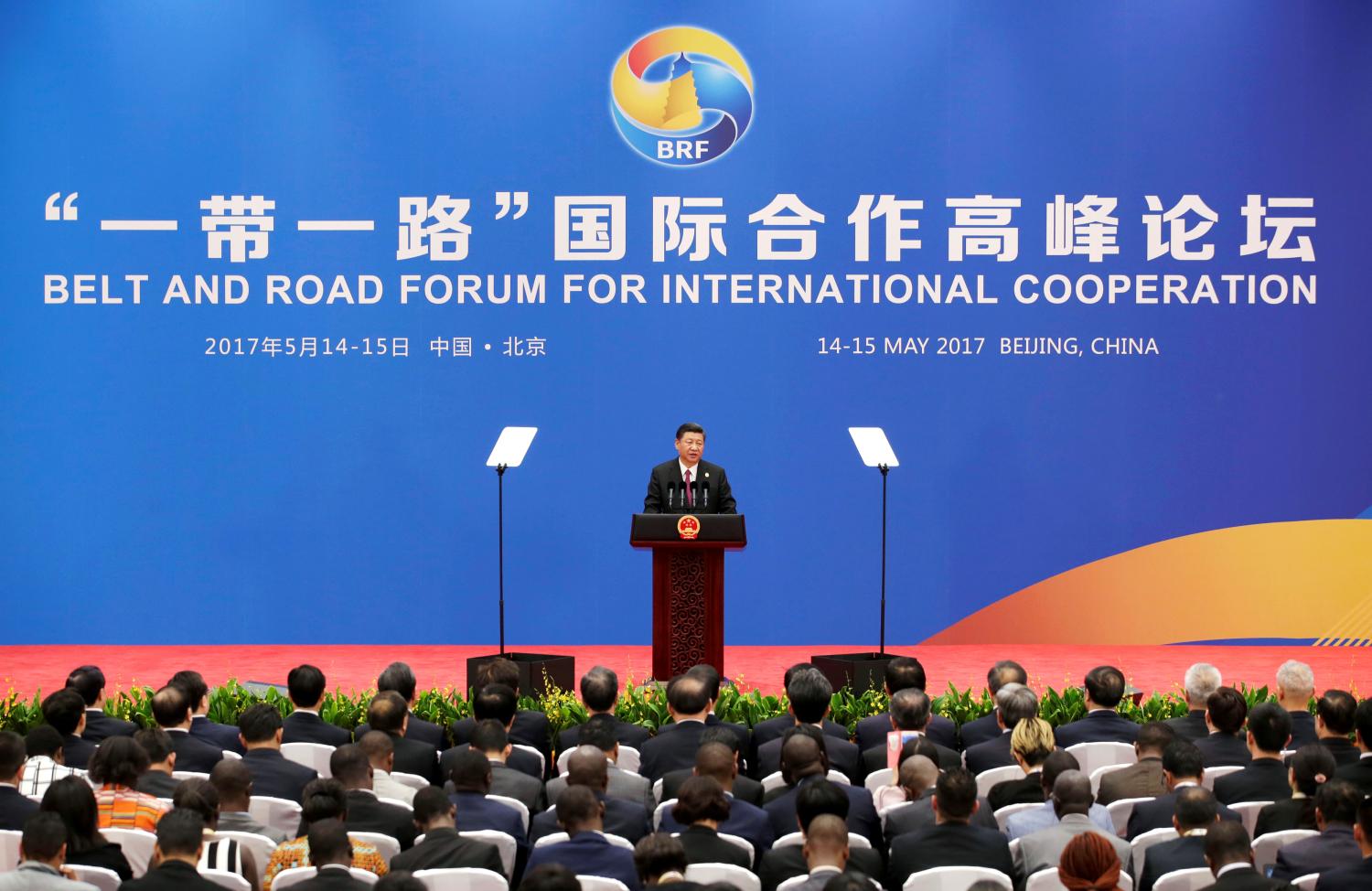

The growing strategic rivalry between the United States and China is driven by shifting power dynamics and competing visions of the future of the international order. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is a leading indicator of the scale of China’s global ambitions. The intent behind the initiative—either economic or strategic—has raised significant concern in the United States and elsewhere. While Beijing portrays the infrastructure development initiative as a benign investment and development project that is economically beneficial to all parties—and in certain cases clearly has been—there are strategic manifestations that contradict this depiction. Washington is skeptical of the initiative, warning of the risks to recipients and the harm it will cause to America’s strategic interests abroad. But many of America’s partners reject the U.S. interpretation and are forging ahead with Beijing. Ahead of China’s second Belt and Road Summit in late April 2019, Brookings Vice President and Director of Foreign Policy Bruce Jones convened seven Brookings scholars—Amar Bhattacharya, David Dollar, Rush Doshi, Ryan Hass, Homi Kharas, Mireya Solís, and Jonathan Stromseth—to interrogate popular perceptions of the initiative, as well as to evaluate the future of BRI and its strategic implications. The edited transcript below reflects their assessment of China’s motivations for launching BRI, its track record to date, regional responses to it, the national security implications of BRI for the United States, as well as potential policy responses. The highlights:

- Originally conceptualized as a “going out” strategy to develop productive outlets for domestic overcapacity and to diversify China’s foreign asset holdings, Beijing later branded the effort as its “Belt and Road Initiative.” While the initiative began with a predominantly economic focus, it has taken on a greater security profile over time.

- China’s initiative has attracted interest from over 150 countries and international organizations in Asia, Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. This is due, in part, to the fact that the initiative is meeting a need and filling a void left by international financial institutions (IFI) as they shifted away from hard infrastructure development. But there is a real possibility that the BRI will follow in the footsteps of the IFIs, encounter the same problems, and falter.

- China has been responsive to requests from recipient countries. This adaptability has made BRI resilient and attractive to recipient governments in spite of popular concerns expressed through the ballot box in multiple countries.

- BRI shouldn’t be seen as a traditional aid program because the Chinese themselves do not see it that way and it certainly does not operate that way. It is a money-making investment and an opportunity for China to increase its connectivity.

- The initiative has a blend of economic, political, and strategic agendas that play out differently in different countries, which is illustrated by China’s approach to resolving debt, accepting payment in cash, commodities, or the lease of assets. The strategic objectives are particularly apparent when it comes to countries where the investment aligns with China’s strategy of developing its access to ports that abut key waterways.

- Japan has long played a quiet but leading role in providing alternative options for recipient countries in need of capital-intensive infrastructure investment. Recently, Tokyo has undertaken significant reforms to elevate its ability to both compete with and complement BRI projects.

- China’s investments in strategically sensitive ports and its development of an overseas military base in Djibouti are of great concern to the United States. Additionally, BRI projects have caused unease in Washington and elsewhere due to their impact on democratic governance, debt sustainability, and existing international environmental and labor standards. Internationally, a growing number of developing countries are themselves expressing concern about Chinese intent.

- U.S. policymakers should adapt American strategy to respond to BRI. Some scholars believe that the right strategy is to multilaterize efforts, while others argue that it is to promote a race-to-the-top dynamic vis-à-vis China. Either strategy requires working proactively with allies and partners to regain the initiative on infrastructure programs, and to pre-emptively ring-fence areas of strategic concern from future Chinese investments. And there need to be increased efforts to foster an independent media in recipient countries that is capable of scrutinizing BRI projects.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).