Children removed from their biological parents because of abuse or neglect enter a child welfare system that is broken and needs to be fixed. The number of children in foster care has nearly doubled in the past 15 years while the number of potential foster families has declined. Foster care was designed to provide a temporary home for children who would eventually be reunited with their parents or adopted. But not all parents can be rehabilitated and many children—older, handicapped, and minority children—are difficult to place in adoptive homes.

This brief argues the need to confront this crisis in the child welfare system by broadening the options available to include congregate care or group homes that would provide a more stable environment for these children.

In early 2000, the Washington Post chronicled a Washington, D.C., child welfare case in which two-year-old Brianna Blackmond was returned from a loving foster family to her biological mother. Within weeks, she was dead. Police are investigating not only how she died, but how the legal and child welfare system failed to protect her from a parent who was not competent to care for her. Cases such as this raise a troubling question: what should be done about the many children who are placed in foster care and whose biological parents cannot be rehabilitated?

When children are removed from their biological parents because of neglect or abuse, they are placed in foster care, kinship care (with relatives), adoptive homes, or, much less frequently, in group homes. These options were designed to address a child’s varied needs and circumstances, but child welfare professionals generally prefer to keep children with their biological parents. This preference comes into serious question when children such as Brianna suffer severe abuse or neglect, or even die, at the hands of their parents.

The child welfare system does not like to give up on any troubled parent because of a long-held belief that given the proper resources, everyone can be rehabilitated. Child welfare workers believe they should make every effort to keep a child within the biological family, and many judges are unwilling to terminate parental rights until an adoptive family is found. The catch-22 is that it is difficult to find people willing to invest in becoming pre-adoptive caregivers if they have no guarantee that they can eventually adopt the child. There is a special sensitivity to removing black children from their extended families because of the fragile nature and constant disruptions of poor black families in the wider society.

This policy brief argues for the need to reorient the child welfare field’s response to the major crises confronting it by widening the options available to include congregate care or group homes. All children deserve the right to grow up in a family setting. This does not always have to mean two biological parents living under the same roof. It can also mean caregivers who provide a stable, safe, and loving environment with consistent discipline, schedules, and routines that help the child develop to his or her full potential.

A Short History of Foster Care

At the beginning of the twentieth century, most large cities had children’s aid societies which “boarded out” children to a sponsor in the community who was paid to raise the child until adoption. The societies also boarded handicapped children and others who were unlikely to be adopted. The modern adoption and foster care systems grew out of those early children’s aid societies, whose ultimate goal was to find adoptive parents. Foster care was seen as short-term care for children who would eventually be reunited with their parents.

Toward the end of the twentieth century, the problems that require removing children from their parents have worsened. Parents who are incarcerated, addicted to drugs, or homeless are unable to provide the quality of care children need. Drug addiction, for example, has had a profound impact on the need for out-of-home care. According to child welfare agencies, drug abuse is associated with 80 percent of substantiated abuse and neglect cases, and a report by the American Enterprise Institute estimates that the number of children in foster care increased about seventy percent because of crack cocaine usage. To the extent possible, support services to keep families together are preferable to those that simply remove the child without aiding the parents. But support services to assist parents with serious mental health or drug problems are in short supply. Moreover, it is very difficult to find adoptive homes for most children over nine years old, so many of them are shuffled back and forth from foster care to their parents’ homes.

Society’s views on what constitutes poor parenting, neglect, and abuse have also changed. The absolute authority parents once wielded and the stricter standards they imposed on children have been replaced by more child-oriented parenting styles and by child abuse hotlines and child protective services that intervene when children are in danger. Greater diversity in the structures and functions of families have given rise to new definitions of what constitutes an effective setting in which to raise children. High divorce rates, never-married parents, and cross-cultural adoption are all evidence of this rapid societal transformation.

The rise in kinship care is another recent development and is a direct result of the view that it is less harmful to place children within the wider family circle, even if some of these placements are less than ideal. Foster care has functioned well for children who can return to rehabilitated parents, for children whose needs are short-term, and for children who can be placed for adoption. It has done less well with the large number of children who cannot be reunited with non-rehabilitated parents or be placed for adoption in a timely manner.

A System Short on Resources

Safely reuniting children with parents who have been neglectful or abusive requires intensive, time-consuming work, because poverty and other systemic issues, such as drug addiction and AIDS, resist quick fixes. The trained social workers charged with doing that work are in short supply in most foster care systems. For example, the District of Columbia Children’s and Family Services Agency was placed in receivership by U.S. District Judge Thomas F. Hogan in 1995 because it failed to provide the proper services to children in its care. At the end of 1999, the court-appointed receiver, Ernestine Jones, reported unacceptably high caseload levels in almost every unit of the agency, and with only two exceptions, the caseloads failed to meet the requirements ordered by the court.

Caseloads are large nationwide because of a short supply of trained child welfare workers who are given insufficient resources to work with children whose needs are increasingly complex. There are no uniform national standards for the training that workers must meet. For example, Washington, D.C. courts require that workers have a master’s degree, making recruitment of staff difficult. The educational requirements in other cities are lower. In D.C., the starting salary for child welfare workers, who are required to have a graduate degree in social work, is $38,000, compared to the starting salary for D.C. teachers with a bachelor’s degree, which is $31,000. The inevitable results are low staff morale and high burnout rates.

A related problem is the “one size fits all” staffing pattern in child welfare agencies. Certification of workers and high standards are very important, but many of the tasks—taking foster children to the doctor, for example—do not require a master’s degree. Differential hiring and use of staff would help ease the burden.

Staff shortages could also be alleviated if federal and local resources were made available to underwrite the formal training of staff at different levels. Tuition and in-service grants, higher salaries, on-the-job resources, and recruitment in high schools could attract more people to the child welfare field. But even with adequate resources, safely reuniting all children with their biological parents will never be possible.

Adoption

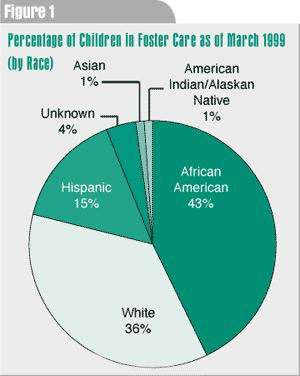

For children who cannot be returned to their original homes, adoption would seem to be the answer. But not all children are easy to place. Healthy white infants are adopted quickly, but older, handicapped, and minority children, along with sibling groups of all races, are not. Figure 1 shows the distribution by race of children in foster care.

As of March 1999, there were 547,000 children in foster care in the United States. Source: AFCARS 1999. Online. Data Available at:

http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/publications/afcars.htm

The reasons for the delays in the adoption process are numerous. Many biological parents are reluctant to relinquish their legal rights even after their children have been in foster care for years. The courts are often slow to terminate parental rights because they, too, believe that biological parenthood supersedes all other considerations. Because society no longer stigmatizes unwed motherhood, many single women facing difficult circumstances often try—and sometimes fail—to keep and raise their children. Therefore, many of the children who come into the foster care system are not healthy newborns. They are older, more damaged, and potentially much harder to place, either for adoption or in foster care. Children can spend years in foster care, being moved from one home to another before a suitable placement is found.

In general, each child who is adopted out of the foster care system spends an average of three years in public care, and about twenty percent remain in public care for five years or longer. A 1991 report on adoptions in twenty states showed that foster children for whom adoption is planned spend an average of four to six years in foster care. The same holds true for the youngest foster children, those who should theoretically be the easiest to place for adoption. In New York City, sixty percent of the infants discharged from hospitals to foster care were still in foster care three years later. Over half of these babies had been placed in more than one foster home since leaving the hospital and one out of six had been in three or more homes, according to a 1993 report by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In March 1999, the mean age of all children waiting to be adopted was eight, and over a quarter of them were over the age of ten.

“Special needs” children are particularly difficult to place. These children are older, members of a minority or sibling group, or have a mental, emotional, or physical handicap. More and more foster children are falling into that category, with roughly eighty percent of parents who adopt children from the child welfare system receiving the special needs adoption subsidy provided by the 1980 Family Reunification Act. Educators report that increasing numbers of foster children require special education because of neurological, physical, and emotional problems.

Legislative Initiatives

The legislative history of child welfare services has swung from an emphasis on family reunification in the 1980s to a somewhat greater emphasis on adoption in recent years. But Congress has never grasped the fact that, for an increasing number of children, neither is appropriate to their particular needs and circumstances.

Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act of 1980

In 1980, Congress enacted the Adoption Assistance and Child Welfare Act, commonly known as the “Family Reunification” Act. An essential feature of the law is permanency planning, which means clarifying the intent of the placement, and, during temporary care, maintaining a plan to permanently place the child. The law mandated that state agencies conduct periodic reviews for each child to reassess the necessity of placement, quality of care, and adequacy of the plan. But it also required state agencies to make “reasonable efforts” to prevent separation from biological parents, and when removal was necessary, agencies were to initiate a speedy reunion with the biological family.

The 1980 law did not successfully address the problems of children whose parents were difficult to rehabilitate. In fact, in a rush to comply with the law, underfunded public welfare agencies returned many children to marginally functioning parents who had not received adequate services to aid in their recovery.

The law also attempted to encourage adoption of children in foster care by setting up a permanent system of subsidies to help adoptive parents secure services for “special needs” children. Despite the subsidies, the adoption of foster care children decreased sharply. In FY1982, 10.4 percent of children leaving foster care were adopted. By 1990, that share had fallen to 7.7 percent.

Adoption and Safe Families Act of 1997

In 1997, Congress tried to address deficiencies in the 1980 law and encourage the adoption of more foster children by passing the Adoption and Safe Families Act. Although the new law still requires states to make reasonable efforts to keep children out of foster care and to return them to the parental home if they are removed, it makes exceptions. States need not make efforts to preserve or reunify a family if a court finds the parent has subjected the child to “aggravated circumstances” such as abandonment, chronic abuse, and sexual abuse. The provision of the law also applies if the parent has killed another of his or her children, committed a felony assault against the child or a sibling, or had his or her parental rights to another child involuntarily terminated. Since the law’s enactment, adoption out of foster care has been on the increase. In 1999, 15 percent of children leaving foster care were adopted.

An Overloaded System

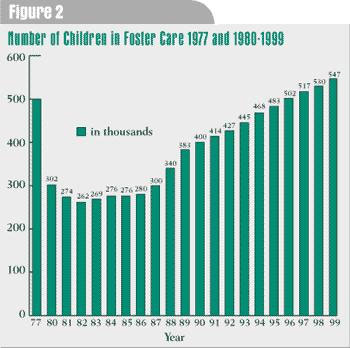

In 1983, there were 269,000 children in foster care, compared with 547,000 children today (see figure 2). In FY2000, federal funding for foster care is $4.5 billion, for adoption assistance, $1 billion, and for Independent Living, $140 million. In FY2001, the Clinton Administration has asked Congress for $5 billion for foster care and $1.2 billion for adoption assistance.

Sources: Data for 1977 from the CQ Researcher (January 1998). Data for 1980-1996 taken from U.S. Committee on Ways and Means; Green Book (May 1998). Child Protection Foster Care and Adoption Assistance. Section 11, pp. 752-53. Data for 1997- March 1999 from Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) for the reporting period 10/1/98 through 3/31/99. Available at:

http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/cb/publications/afcars.htm

.

Although the number of children in foster care has nearly doubled in the past 15 years, the number of potential foster families has declined. An overloaded system is attempting to provide care for children for whom it was neither created, nor is currently configured to serve. In fact, although the number of children in foster care is rising, the number of new admissions into care is not. (Admissions have been up and down since 1994.) This suggests that the rising number of children in foster care is due to increases in the length of stay or to changes in the mix of children entering care.

Fixing the System: Congregate Care?

The child welfare system is broken and needs to be fixed. There are more children than ever in foster care, too few social workers and potential adoptive parents, a declining number of potential foster families, and fewer children being returned to their biological families. The question is what to do with children who are unlikely either to be reunited with their parents or adopted. The option of congregate (institutional) care bears examination.

Throughout most of the twentieth century, the popularity of congregate care steadily declined. Indeed, child welfare institutions came to be regarded as bleak, Dickensian warehouses managed by cruel, untrained, and uncaring functionaries. Some criticism directed at the institutions was well-founded and led to the closing of substandard facilities. By the latter half of the century, very few warehouse-style institutions for children existed. In addition, the deinstitutionalization movement that swept through all types of large group facilities (i.e., mental institutions, homes for juvenile delinquents, and orphanages) in the United States helped close all traditional institutional facilities for children. In their place—apparently without widespread knowledge by the public or even to many child welfare professionals—grew modern congregate care facilities, primarily a collection of family-style group homes staffed by trained childcare workers.

Some elected officials, frustrated by the difficulty of solving the myriad problems affecting children with special needs, have advocated reestablishing orphanages. In 1994, just before he became Speaker of the House, Rep. Newt Gingrich (R-Georgia) set off a highly-charged national debate when he suggested that “orphanages” be revived to care for the children of young and welfare-dependent single mothers. Child welfare practitioners, policy analysts, and scholars attacked Gingrich’s statement, saying that large and impersonal orphanages stymied healthy child development. Child care workers at congregate facilities generally answered the critics by demonstrating that modern-day orphanages are in fact more likely to resemble a suburban home or, as in the case of the highly-regarded international SOS Children’s Villages, a group of well-kept, campus-style homes. Founded by Hermann Gmeiner in Austria, the program attempts to replicate a family setting by including a mother, brothers and sisters, and a house where they live permanently. Children’s Villages are now located in Europe, Asia, Latin America, and Africa, and efforts are under way to establish one in Washington, D.C.

Another model of a congregate care facility in the United States is The Villages, founded in 1964 by Dr. Karl Menninger, whose aim was to give children permanent homes. The Villages, which now include eleven homes in Kansas, were founded on the model of placing children in a home with surrogate parents for as long as necessary without moving them from one foster home to another. According to a 1994 article in the Atlantic Monthly by Mary Lou Weisman, the children who live at The Villages observe such old-fashioned values as church attendance, neat dress, daily chores, set bedtimes, clean rooms, and obedience to adults. Counseling is available to children, as is access to psychotropic medications when necessary.

The oldest congregate care facility in the United States is Girard College, which was founded by philanthropist Stephen Girard and was opened in Philadelphia in 1848 to care for and educate children in need. Girard, who was the richest man in America when he died, believed that children should be given the opportunity to cultivate the skills necessary for a successful life. Today, Girard College continues to help underserved children by providing boarding and education at no cost to every child who attends school, which is housed on a 43-acre campus. It is home to over 600 boys and girls in Grades 1 through 12, virtually all of whom come from single-parent, lower income homes.

An Equal Place for Congregate Care

The unique value of congregate care is that it can provide permanent homes and care by trained professionals for children who are unlikely to be adopted or to be placed in the stable, specialized (i.e., therapeutic) foster homes they require. Although congregate care is not appropriate for every child, it can help alleviate both overcrowding and inappropriate foster care placements.

As noted, many child welfare professionals and the public prefer adoption and foster care to congregate care because they believe that the optimal environment for children’s development is in a nuclear family setting. Almost certainly, they are correct. However, the fact is that fewer and fewer Americans are living in the traditional nuclear family, and that ideal family setting is virtually unattainable for many children now in public care. Care in congregate homes is certainly preferable to the care of biological parents who are neglectful and abusive. It is also preferable to the revolving door experience of too many children in foster care. Children who have been damaged in their biological families and from multiple foster care placements can find in congregate care skills to cope effectively and make a successful transition to adulthood.

The child welfare system should give it an equal place in the continuum of care options, along with adoption, foster care, and kinship care. The type of care a child receives should depend on his or her circumstances, and the driving force at all times must be to provide stable, long-term care. Family reunification and kinship care should not take precedence over the child’s needs for stability. Congregate care cannot solve all of the problems besetting the child welfare system, but it provides a good alternative for many children.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).