Australia’s Climate Change Policy – Laggard to Leader

Over the last five years Australia has gone from dragging its feet on climate change to being a leader in climate change policy. Prior to 2007 – when Australia signed the Kyoto Protocol – it was the only other country along with the U.S., Afghanistan and Sudan not to have done so. Australia’s transformation into a climate leader was capped off on July, 1 2012 with the implementation of an A$23.00 carbon tax, which will rise 2.5 percent per year and will transition to a cap and trade system on July, 1 2015.

Carbon pricing is the main policy adopted by the Australian government to reach its national target of reducing its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions to 5 percent below 2000 levels. Reaching this target by 2020 will require a total reduction in GHG emissions of approximately 13 percent given Australia’s Kyoto Protocol target of 108 percent over 1990 levels. [1] Similar to the EU, Australia has also committed to more ambitious but conditional mitigation targets for 2020 based on two different scenarios. In the event of an ambitious global agreement to stabilize atmospheric concentration of GHG emissions at 450 part per million, Australia will aim for a reduction of 25 percent below 1990 levels; if there is a global agreement that will not stabilize emissions at 450ppm but does involve “major developing countries committing to substantially restraining their emissions and advanced economies taking on commitments comparable to Australia’s,” it will aim for 15 percent below 2000 levels. Australia has also set itself a goal of reducing its GHG emissions by 80 percent below 2000 levels by 2050.

In comparison, the U.S. has adopted a target of reducing its GHG emissions by around 17 percent below 2005 levels by 2020 and by 80 percent below 2005 levels by 2050. But unlike Australia, the U.S. is not using a carbon price to achieve its GHG mitigation target and instead is relying on a range of regulatory measures, such as Environment Protection Agency standards for CO2 emissions, tighter vehicle fuel efficiency standards and promoting energy efficiency.

Both Australia and U.S. targets are enshrined in the so-called Cancun Agreements that came out of the Cancun U.N. climate change negotiations in December 2010.

Why What Australia Does Matters for the U.S.

Australia’s climate change leadership and particularly its carbon pricing should be of deep interest for the U.S., not only for its contribution to reducing global GHG emissions but also because Australia and the U.S. share enough similarities when it comes to addressing climate change that Australia should, in many respects, be seen as an important laboratory and learning opportunity for those in the U.S. thinking about climate change and energy policy.

Given that most economic activity produces GHGs, from driving cars to heating houses to running businesses, reducing GHG emissions will require significant economic and social transformations. How countries respond to these challenges will be influenced by factors such as geography, culture and lifestyle. In this regard, Australia and the US share a number of similar characteristics that makes reducing GHG emissions particularly challenging. For one, Australia and the U.S. are both large continents – Australia is almost the same size as the U.S. lower 48 states. The U.S. population of 315 million is almost 15 times larger than Australia’s population of 22 million, but Australia and the U.S. have the first and second highest GHG emissions per capita. Moreover, the space and size of Australia and the U.S. have underpinned the need for long roads, large cars, and allowed for living in houses in extended suburbs. Australia and the U.S. have been built for this lifestyle – the infrastructure, systems of government and businesses are geared to servicing, providing for and maintaining this scheme. As a result, Australia and the U.S. will face similar costs in reaching the ambitious GHG mitigation targets set for 2050 not only in economic terms, but also in terms of lifestyle and ultimately national outlook as increased urban density and use of public transport become necessary.

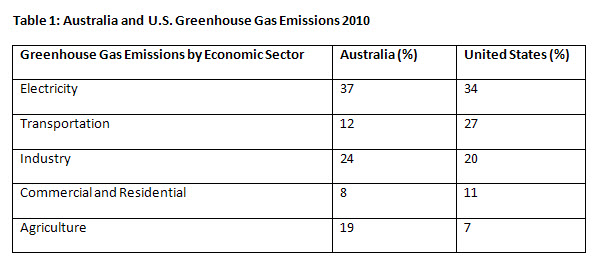

These similarities also underpin the two country’s similar GHG emissions profiles. As can be seen below in Table 1, emissions from the electricity, industrial and commercial and residential sectors comprise very similar percentages of each countries total GHG emissions. And while Australia produces significantly more GHG emissions from agriculture than the U.S., this sector has been exempted from the carbon tax.

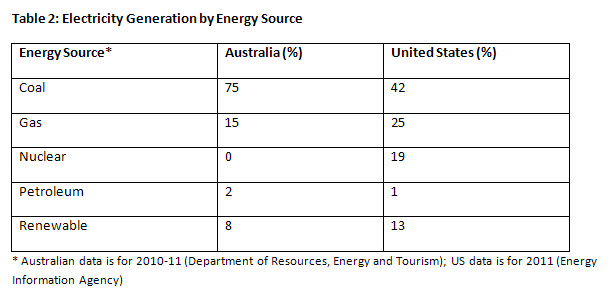

One of the key challenges for Australia and the U.S. in reducing their GHG emissions will come from the electricity sector, where alternatives to coal – the largest source of GHG emissions in both countries – are not yet economically viable (see Table 2). Moreover, coal fired power stations are sunk capital costs and will remain online for decades to come, which means coal will only slowly decline as a share of each country’s electricity generation. In addition, carbon capture and storage – the most promising solution to CO2 emissions from power generation – remains untested.

Australia is also significantly more dependent on coal as a source of electricity than the U.S. – which represents 75 percent of its electricity generation compared to 42 percent in the U.S. (see Table 2). Australia, like the U.S., also has large natural gas resources, however, it has no nuclear power – a source of base-load low carbon energy. Although Australia has approximately 23 percent of the world’s uranium reserves, there is currently no political support for building nuclear power stations. These factors highlight that reducing CO2 emissions from the electricity sector will be significantly more challenging for Australia than for the U.S.

Why Now?

Given Australia’s challenges to reducing its GHG emissions, it is worth considering why Australia – a country that produces a mere 1.5 percent of global GHG emissions – has decided to forge ahead while there is limited climate change progress in the U.S. and in the U.N. climate change negotiations. As will be demonstrated, the key factors that have motivated Australia’s climate change policy are also present for the U.S. and could be expected to drive more ambitious U.S. climate change action over time.

Economic factors have been a key driver of Australia’s decision to introduce a price on carbon. On the one hand, those opposed to climate change action have emphasized its costs. However, it is clear that the costs of reducing GHG emissions to meet the type of targets outlined above become costlier over time, meaning it is cheaper to start addressing climate change immediately. Economic modeling by the Australian Treasury has concluded that delaying global action by three years will increase the first year’s mitigation costs by 30 percent. Moreover, the cost of a carbon price is expected to slow Australia’s average income growth by only around 0.1 percent per year. [2]

Australia’s decision to price carbon was also influenced by its growing role as a major exporter of primary energy, with coal and liquefied natural gas (LNG) being the largest and second largest export earners. Pricing carbon is a strategy to avoid these exports becoming subject to the type of border tax adjustments that were proposed in the 2009 U.S. Waxman-Markey Climate Change bill, which would have extended the domestic carbon price to carbon intensive imports. The EU’s recent inclusion of all airlines departing and leaving EU airspace in its cap and trade system– which includes all EU airlines and those non-EU airlines coming from countries without a comparable carbon price on airlines CO2 emissions – is another example of how a failure to price carbon domestically can lead to exports being subject to a carbon price in foreign jurisdictions. Similarly, as the U.S. becomes an LNG exporter – and possibly expands its exports of coal – the relationship between domestic climate change action and U.S. energy exports should feature more prominently in its climate change debate. [3]

The Australian government is also committed to the productivity and competitiveness improvements that flow from pricing carbon. In economic terms, pricing carbon is an efficient market outcome that internalizes the social costs of GHG emissions. This should drive structural changes in the Australian economy as resources move away from carbon intensive industries towards sectors that will become increasingly competitive as a result of a carbon price, such as gas production, renewable energy and associated services industries. Reducing the carbon intensity of the Australian economy is also consistent with the global push towards green growth in international settings such as the G-20 and Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. President Obama’s support for climate change action is also focused on restructuring the U.S. economy in ways that will reduce U.S. GHG emissions and create an industrial base that can take advantage of the economic opportunities created by the expected growth in demand for green goods.[4] This has led the U.S. Government to invest in renewable energy, support the U.S. battery industry and expand clean energy research and development.

Climate change also has national security implications for Australia, particularly in the Asia-Pacific region. Rising sea levels from ice-melt caused by climate change threaten to completely inundate some pacific islands and Australia would be expected to bear a fair share of these costs, including accepting climate change refugees. Even in the absence of such catastrophic outcomes, rising sea levels combined with a warmer and more volatile climate will pose new risks for already fragile states in the Pacific such as Papua New Guinea, Fiji and even Indonesia. While Australia’s climate change efforts alone will be too small to stave off such outcomes, leadership on climate change, such as demonstrating that a GHG intensive economy can reduce emissions at low cost, can have important effects for more ambitious climate change action in other countries, including the U.S. The national security implications of climate change can also be expected to increasingly drive the climate change debate in the U.S. Recently, US Defense Secretary Leon Panetta has declared climate change to have a dramatic effect on U.S. national security, as rising sea levels, droughts and melting of the polar ice caps increase demands for humanitarian assistance and disaster relief. [5]

The Politics of Pricing Carbon

The politics of climate change are particularly difficult because of its temporal nature – the costs are immediate and identifiable – and the benefits are longer term and more difficult to quantify. Such a paradigm fits poorly with the focus of politicians on two to six year election cycles. Australia’s political experiences in negotiating the politics of climate change also provide some lessons for the U.S.

Pricing carbon is a major economic reform. But the fact that governments on the political left are advocating for market mechanisms such as pricing carbon to address climate change and conservative parties are opposing these measures speaks to the challenges of building political consensus on this issue. In Australia, the left leading Labor government drew on its history of leadership in economic reforms to emphasize pricing carbon as an important economic issue. This allowed the government to shift the debate towards the economic advantages of pricing carbon, including the development of new industries such as renewable energy. However, and as outlined above, there are immediate costs to pricing carbon, which means that governments need to also ensure that there is broad understanding of why people will, over time, be better off with a carbon price.

This leads to the key lesson from Australia’s political battles over carbon pricing: a strategy that seeks to reach agreement amongst key stakeholders only – what in Washington would be considered an inside-the-beltway strategy – will likely fail. This is what characterized the Australian Rudd government’s initial failed attempts to pass a cap and trade bill, as well as the failed efforts by the U.S. democrats to get enough votes in the Senate to pass a cap and trade bill. It is the challenges of pricing carbon outlined above – the temporal mismatch between costs and benefits and the need for climate policy to apply for the long term – that requires buy-in from the broader community into why pricing carbon is important.

Secondly, the economic dimension of climate change and carbon pricing should be front and center of any messaging. This means that the U.S. Treasury and key economic players in the White House would need to lead any renewed push for climate change legislation. A narrative that emphasizes pricing carbon as a market driven response and highlights the economic opportunities will also be important.

How Australia fares in reducing its GHG emissions and at what cost will only become clear over time. But certainly the challenges for Australia will be no less than what the U.S. will face should it decide to price carbon and aim for similarly ambitious GHG mitigation targets. These reasons alone recommend close U.S. attention to Australia’s experience.

[1] 1990 is the baseline year used in the Kyoto Protocol. Australia’s post-Kyoto targets use 2000 as the baseline. Australia’s GHG emissions grew by 1 percent from 1990-2000.

[2] Australian Government Treasury – Strong Growth, Low Pollution: Modeling a Carbon Price, July 2011.

[3] Charles Ebinger, Kevin Massy, Govinda Avasarala, “Liquid Markets: Assessing the Case for U.S. Exports of Liquefied Natural Gas”, Brookings Policy Brief 12-01, May 2012.

[4] President Obama’s State-of-the-Union Speech 2012.

[5] Speech at the Environmental Defense Fund, May 2, 2012 – www.defense.gov/news/newsarticle.aspx?id=116192

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edCarbon Pricing in Australia: Lessons for the United States

July 2, 2012