Recently, some Egyptian officials have blamed the IMF for delays in reaching an agreement over a $4.8 billion loan to the country. Apparently, the government has included all of the IMF’s technical requirements (e.g. phasing out subsidies and raising taxes) in its economic program. However, officials complain that the IMF is still not satisfied and would like to see more political consensus around the economic reform program. In view of the current economic and political situation in Egypt, it is hard to blame the IMF. A call for greater consensus seems to be quite appropriate.

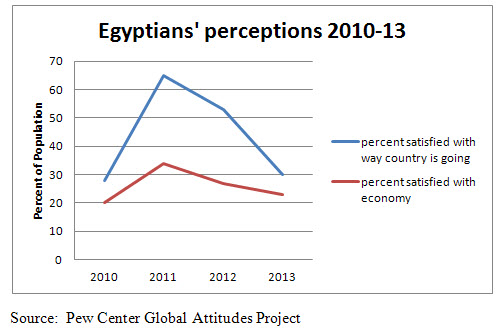

Egyptians’ initial excitement following the revolution has given way to disappointment. According to the Pew Research Center’s “global attitudes project,” about 56 percent of Egyptians are unhappy with the way their nascent democracy is functioning. The graph below shows that the percentage of Egyptians who are satisfied with the general direction their country is taking and those satisfied with economic conditions rose sharply following the revolution in 2011. However, it fell again starting 2012, and today Egyptians’ level of satisfaction is roughly as low as in 2010, just before the revolution.

The country continues to be deeply polarized between Islamists and secularists. There is no consensus on the new (Islamist-leaning) constitution that was just passed in December 2012. According to the Pew Center’s survey, 49 percent of Egyptians favor the constitution while 45 percent oppose it. Similarly, 46 percent of Egyptians believe that the upcoming parliamentary elections will be fair, but 40 percent expect them to be unfair. Only about 50 percent of Egyptians plan to vote in those elections (the participation rate in December 2012’s constitutional referendum was less than 33 percent).

Youth who oppose President Morsi (the “tamarod” movement) are collecting signatures on a petition to impeach him and call for early elections. They say that they are close to their target of 15 million signatures. Nation-wide anti-Morsi protests are planned for June 30, the first anniversary of his election.

Violence, especially against women, has increased. Peaceful demonstrations in Tahrir Square that exemplified “people power” and succeeded in bringing down a dictator have morphed into street battles in which scores are injured or killed. Women’s rights are on the decline. Women participating in peaceful protest face sexual violence and even rape.

Civil society is very worried. Constraints on its freedom are as severe as ever. A court has recently convicted 43 non-governmental organization (NGO) workers and handed down prison sentences. The harsh treatment of the democracy NGOs, coupled with the presentation of a new restrictive NGO law to the upper house of parliament, is discouraging Egyptian civil society organizations and is limiting their ability to participate in the country’s economic development.

Phasing out fuel subsidies and raising some taxes may be necessary for macro-economic stabilization. But the initial impact of those policies would probably be painful for millions of poor and middle-class people in Egypt.

For the 85 percent of Egyptians who live on $5 or less per day, economic hardship is on the rise. Growth is down and unemployment is up. Egyptians are finding it hard to obtain key necessities. Early morning visitors to Cairo’s poorer neighborhoods see long lines of people waiting to buy subsidized bread. For some of them, the wait will have been in vain as they will not get any. There are also long lines of cars and trucks in front of gas stations waiting to buy subsidized fuel.

It is hard to see how any government can implement economic reforms under those circumstances. Phasing out fuel subsidies and raising some taxes may be necessary for macro-economic stabilization. But the initial impact of those policies would probably be painful for millions of poor and middle-class people in Egypt. In the absence of a minimum level of political consensus, as well as popular understanding and support for the economic reform program, those measures would be impossible to implement. They could lead to more unrest and street violence, as happened when President Sadat tried to remove subsidies in the late 1970s.

The IMF is right to advocate for broad-based political support for the reforms. Experiences from around the world demonstrate that successful implementation of economic reforms requires broad national consultations and some degree of political consensus. Hence, the Egyptian government should try to build bridges to the opposition and to take steps that could reduce polarization. This would also involve making its economic program public and reaching out to opposition groups and civil society to try to build a common understanding of economic challenges and possible solutions.

The vast majority of Egyptians continue to place a high value on democratic principles. According to the Pew Center survey, more than 60 percent of Egyptians believe that democracy is the best system of government, and that it will eventually solve their country’s problems. The same survey shows that Egyptians’ top priorities are: better economic conditions, a fair judiciary, law and order, uncensored media, honest elections and free speech. This would seem to imply that efforts at greater transparency and inclusiveness in economic policy making would be well received by a majority of Egyptians. They would probably also help reassure the IMF.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edCan Egypt Really Blame the IMF?

June 19, 2013