A generation has been lost in the journey towards race equality in terms of income. The income gap between blacks and whites has been stuck since 1980. Why? Dozens of factors count, of course, but one in particular is worth further exploration: the underrepresentation of black students in elite colleges. As I noted in a previous blog, this could help to explain why blacks earn less than whites, even in the same occupation and with the same level of education.

Race Gaps at Elite Colleges

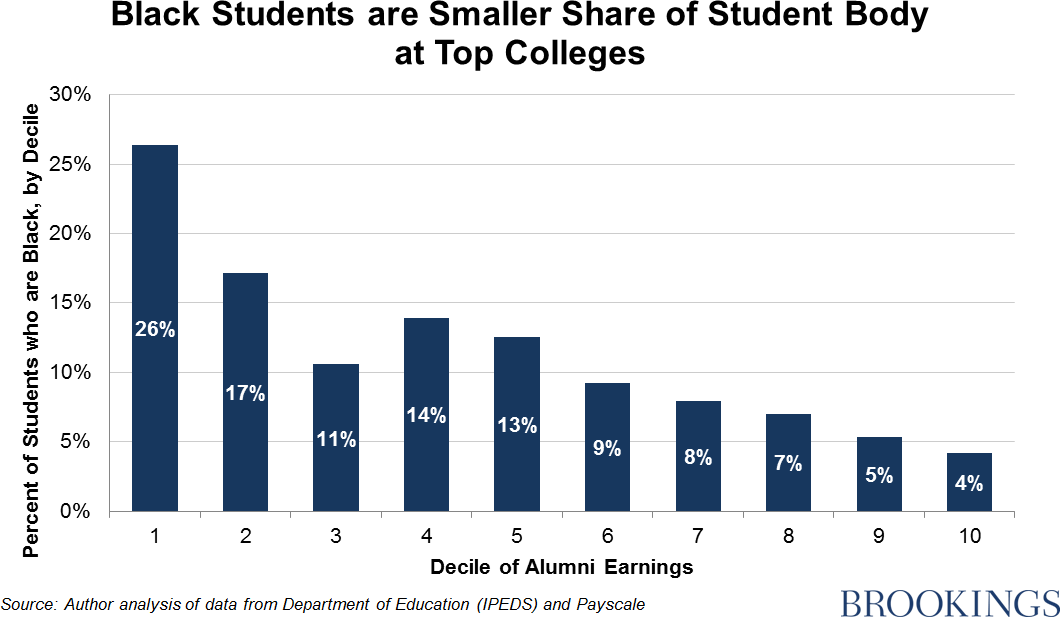

Black students make up just 4% of undergraduate enrollees in the top decile of the nation’s four-year colleges, ranked by mid-career alumni earning figures. By contrast, 26% of students in the bottom rank of colleges are black:

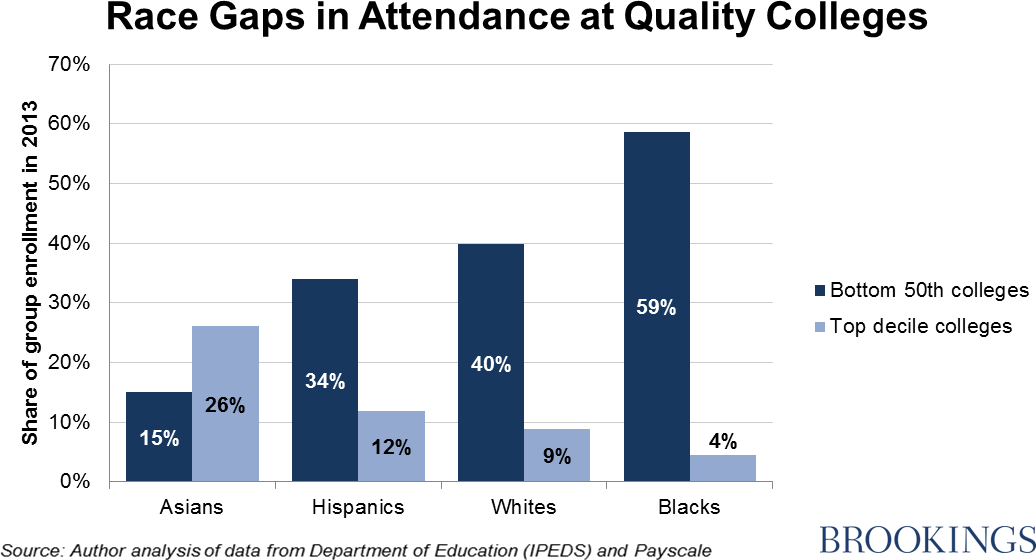

Most of the small number of black graduates from the 92 schools in the top decile will go on to successful careers. The problem is that a vastly larger number of blacks – 59% – attend colleges ranked in the bottom half, with just 4 percent in top schools. By contrast, 9% of white students attend top colleges and 26 % of Asians.

The skills acquired at the lower-ranked schools appear to be less valuable to employers than those acquired at higher rates colleges, resulting in weaker earnings opportunities, consistent with recent research and a forthcoming report of mine.

Rising Black College Enrollment – But Mostly At the Bottom

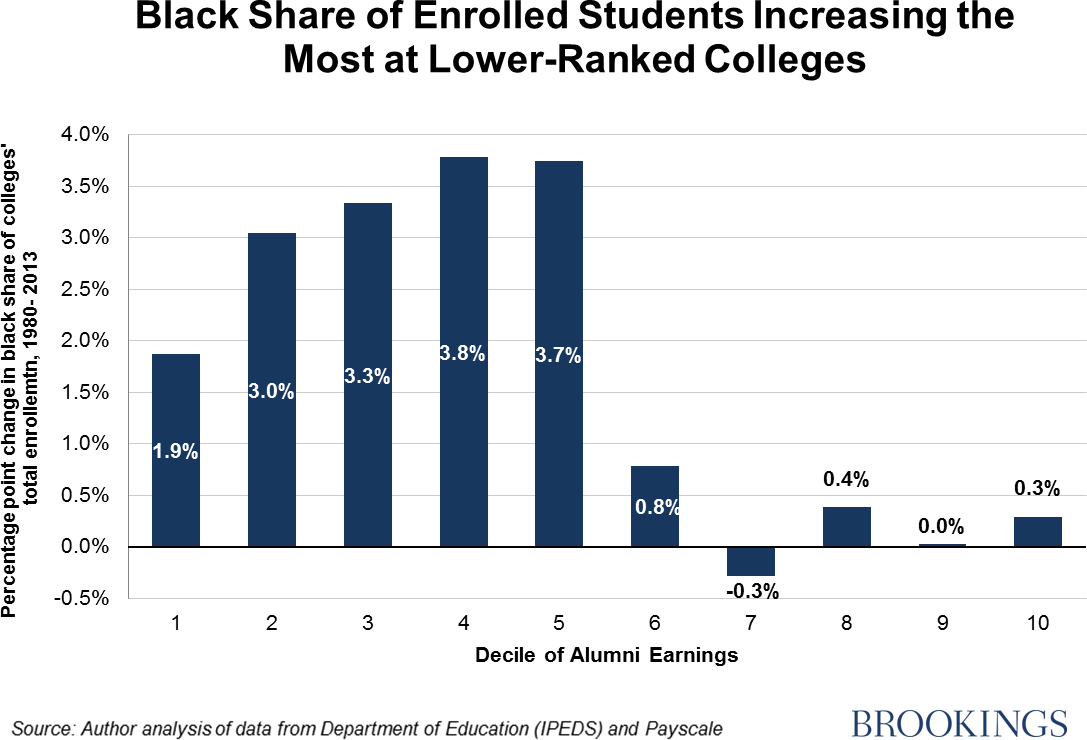

Are things getting better? Not on this front. While the number of blacks enrolling in top colleges increased from 1980 to 2013, the share of black students at such colleges and the likelihood of a black college student attending top colleges have not. The change in black enrollment shares at top decile colleges between 1980 and 2013 was just 0.3 percentage points, and the percentage of black students attending such schools fell from 6 to 4 percent. Most of gains have been in lower tier colleges:

A Geographic Divide

These national trends masks considerable variation across colleges, however, which result in part from regional demographics. At a number of elite southern colleges, black enrollment rose appreciably. At Duke University in North Carolina black enrollment shares doubled from 5% to 10% percent. At Vanderbilt in Tennessee black enrollment went from 3% to 8%, and at Houston’s Rice University, enrollment went from 4% to 6%.

In California, the picture is much worse. At University of California campuses in Irvine, Los Angeles, San Diego, and Berkeley, black enrollment shares fell by 1-4 percentage points, and currently stand between 1-2%. Just 4 percent of the University of Southern California’s students are black, compared to 7 percent in 1980. Meanwhile there have been large jumps in Californian enrollment rates for both Asians and Hispanics.

Black Americans have a distinctly worse experience than other racial groups in terms of college quality. This is not to say the problem is solely with the college system: the gaps reflect the accumulated disadvantages of the prior eighteen years. But it serves as a stark reminder of the depth of the challenge.

Commentary

Black Students at Top Colleges: Exceptions, Not the Rule

February 3, 2015