Remarks prepared for “Fighting Inequality: Leveraging Opportunities for Innovation,” Project on Municipal Innovation, September 24, Harvard Kennedy School.

I told a colleague I was going to give a talk about inequality, but that I had to do it over dessert, and I wasn’t sure how that was going to go over. She said, “It’s perfect … let them eat cake.”

Ben and Steven and the good folks at Living Cities invited me here tonight because inequality is a key theme of your gathering over the next day.

And inequality, particularly in big cities, is something that’s been a bigger part of the national dialogue over the past few years, probably starting with Occupy Wall Street in 2011.

Soon thereafter in 2013, there were a series of elections across many of your cities where the issue of inequality, and what mayors should do about it, was a big part of the debate. New York, Minneapolis, Boston, Seattle, Los Angeles, and others.

This was no straw man issue. Inequality is indeed high and rising in many American cities.

San Francisco seems to be the quintessential example, and with good reason. The Chronicle ran a piece a couple weeks back entitled, “San Francisco’s strange detour from paradise to parody.” It quoted a longtime resident of the Mission District, ground zero for the city’s gentrification:

“I live one block away from Valencia Street, where there’s a new restaurant that opens up every 15 minutes. How many chocolate shops does Valencia need?”

About a one-bedroom apartment in the Mission advertised for $6,800/month: “I did the math: $80,000 for rent for a year? You could buy three houses in Buffalo.”

But these absurd stories and my previous work on inequality weren’t really the impetus for my talk, or for the conversations you’ll have tomorrow.

Rather, I think what drove this focus was the events that unfolded in Baltimore back in April and May, which came in close proximity to others in Ferguson, Mo.; in Staten Island, N.Y.; in North Charleston, S.C.

The obvious common thread was the tragic death of an African American male at the hands of police … and the tensions they exposed between minority communities and law enforcement, bred in part by a long history of misguided criminal justice practices and policies.

You can see this tension in the words of West Baltimore residents quoted in the Baltimore Sun during the days of the unrest. Here are a few:

– Resa Burton, a lifelong West Baltimore resident: “They killed a man, but it could’ve been me! It could’ve been me! It could been my brother, my nephew! It could’ve been you!”

– Vaughn DeVaughn, a city teacher: “This is about anger and frustration and them not knowing how to express it.”

– Sandra Almond-Cooper, president of the Mondawmin Neighborhood Improvement Association: “These kids are just angry,” Almond-Cooper said. “These are the same kids they [meaning the police] pull up on the corner for no reason.”

These are the very real, very raw surface issues that Freddie Gray’s death—and Michael Brown’s, and Eric Garner’s, and Walter Scott’s—exposed.

Several weeks after the unrest, a video team from Brookings went to West Baltimore, and talked to a number of young people. I highly recommend the video, you can Google “Brookings Baltimore” to find it. Here were some of the quotes from the young people in that video:

“Within my community, everything is divided. You have one community, and you cross the street, into a complete other community where the poverty, and the neighborhood, and the people are completely different, even though we’re just five minutes away.”

“Where I live, you’ve got houses that are boarded up, and have trash.”

“Everything is still segregated, opportunities are different, kids aren’t allowed to go to certain schools, if they do, they won’t feel comfortable, they’ll feel like outcasts in those schools.”

“Educational opportunities in my neighborhood are poor.”

It was those underlying issues, issues that lie at the confluence of race, place, and opportunity in America, that motivated a colleague and I (a Baltimore resident) to write a piece in the wake of the unrest.

We called it, “Good fortune, dire poverty, and inequality in Baltimore: An American story.” The title was more about the art of search engine optimization than anything else.

But we wrote it in part as a response to the emerging narratives in the media about the deeper structural issues in Baltimore that fueled the unrest. Narratives like:

– Baltimore is “The Wire.” It’s “Homicide: Life on the Street.” It’s a dangerous city overrun by crime and the drug trade. Or

– Baltimore is a city of extremes. It’s gentrifying rapidly and people feel threatened. Or

– Baltimore is one of the very poorest American cities. It has no fiscal base to improve city services.

We thought that the truth, as usual, lay somewhere in the middle of all these interpretations.

But we also thought that for all that makes Baltimore a unique place—I married into a Baltimore family, so I’ve seen some of that uniqueness firsthand—the city is hardly alone when it comes to these deeper structural issues. On those fronts, it often looks like a very typical American city.

The charts and the maps you see around the room tonight are adapted in part from that piece. They compare Baltimore to the other cities that are part of the Project on Municipal Innovation. Let me just briefly walk through the story I think they tell.

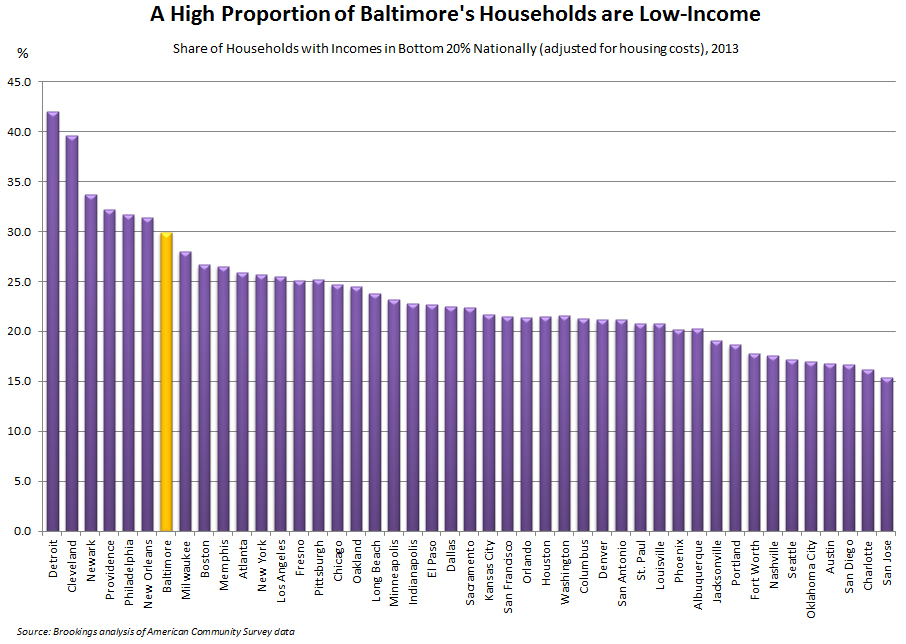

First, Baltimore does indeed have deep poverty. Adjusted for the cost of living, about 30 percent of Baltimore’s households have incomes in the bottom 20 percent nationally. That’s quite high, although a number of cities—Cleveland, Detroit, Newark, Providence, Philadelphia, and New Orleans—exhibit even deeper poverty.

We know that low levels of income make it very difficult for these families to get by, for children to succeed in school, and for cities to fund the critical services that improve opportunities and quality of life for all.

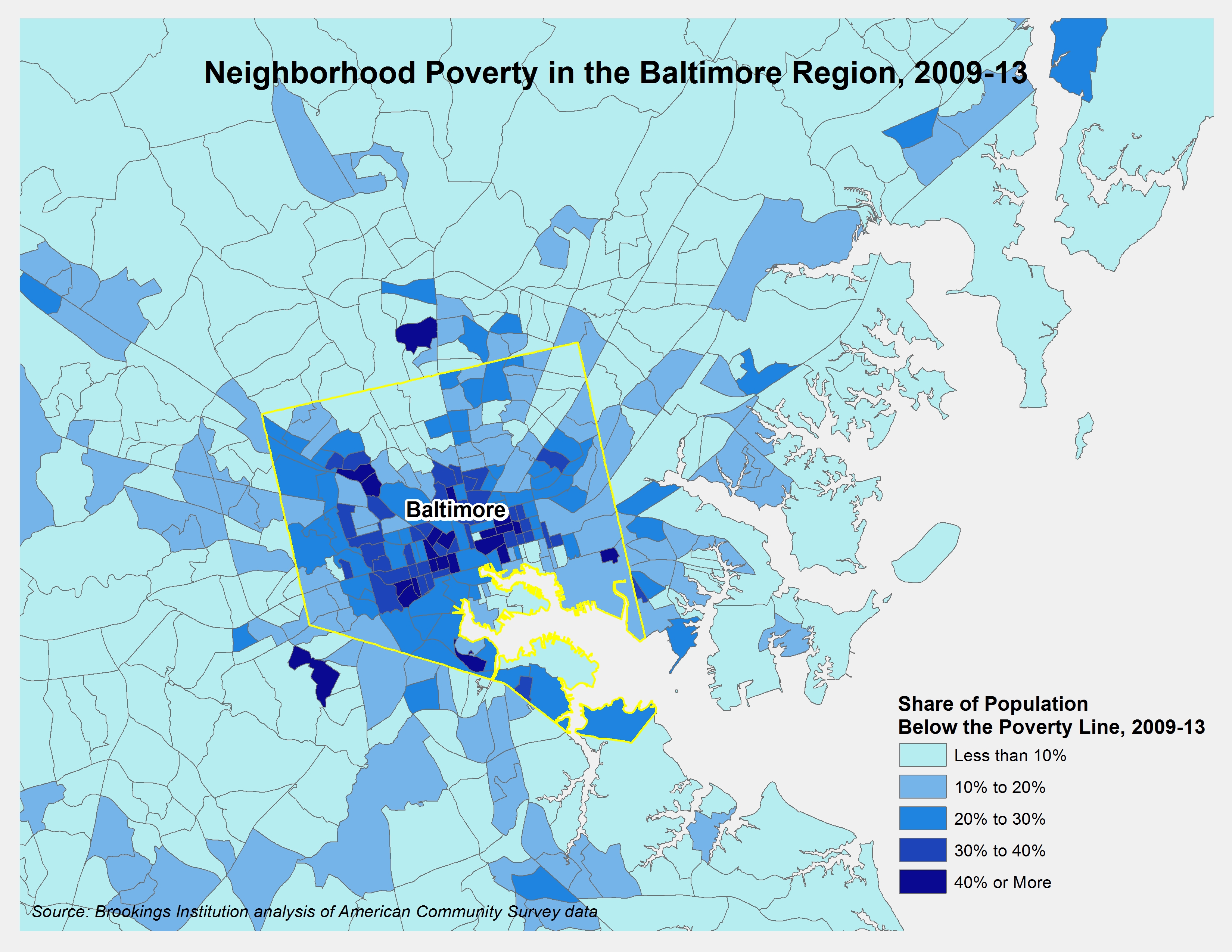

Second, poverty doesn’t spread evenly. This map shows that many of Baltimore’s poor households are concentrated on the city’s west and east sides, including the Sandtown-Winchester neighborhood where Freddie Gray lived and the unrest occurred. We know that this form of concentrated poverty limits educational opportunities, fuels disinvestment, and causes physical and mental health challenges for residents who live amid it.

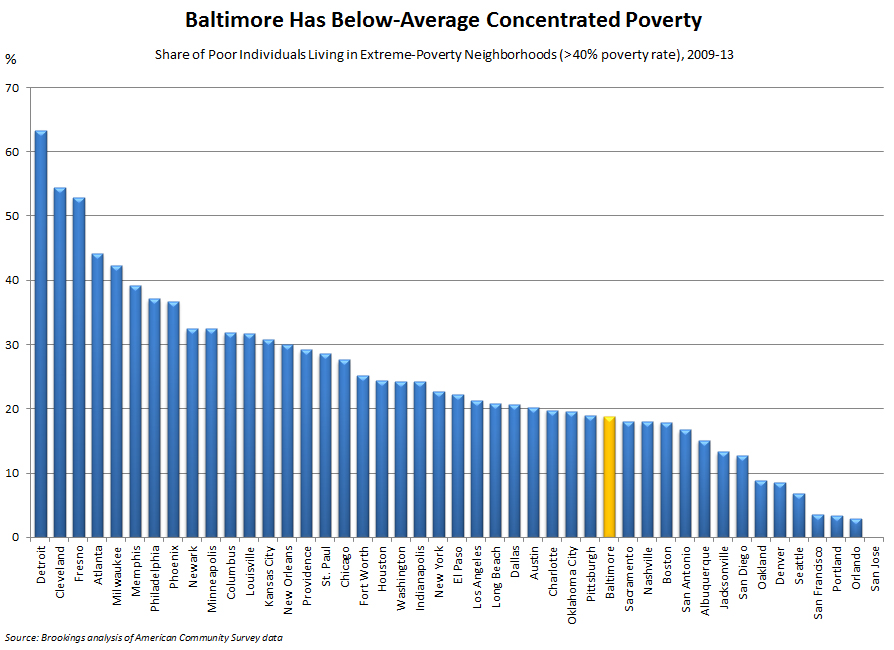

However, Baltimore is hardly an outlier on concentrated poverty. This chart shows that actually, Baltimore’s poor households are less concentrated in extremely poor neighborhoods than poor households in many other big cities. In Baltimore, about one in five poor residents lives in a neighborhood where the poverty rate exceeds 40 percent. In Milwaukee, for instance, double that share live in an extreme-poverty neighborhood.

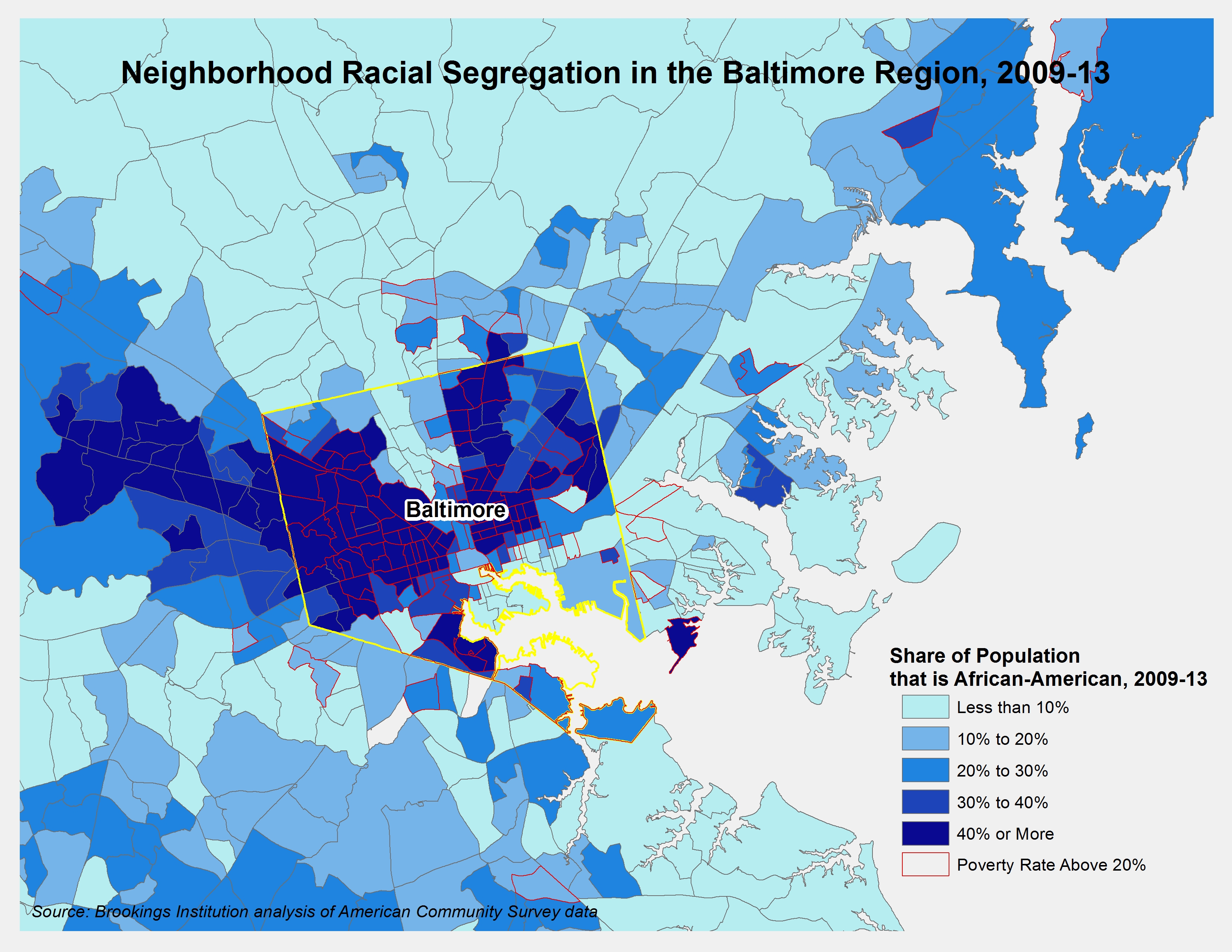

Third, issues of poverty and concentrated poverty in Baltimore dovetail with divisions by race. The poverty rate for black children in Baltimore is three times as high as that for white children. And as this map shows, the Baltimore neighborhoods with the highest rates of poverty are generally those with the largest African American population shares.

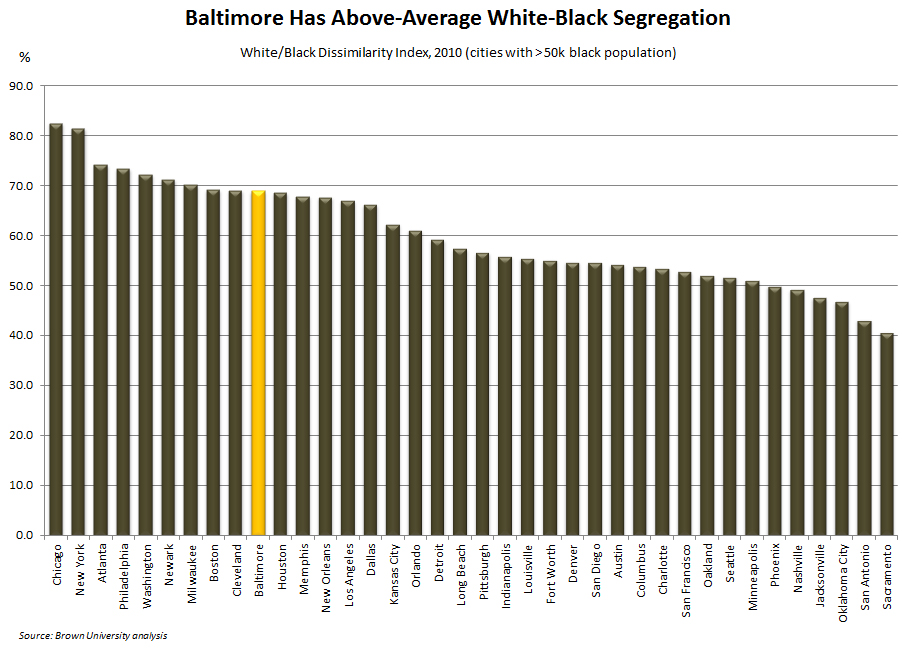

But the high level of racial segregation that helps to perpetuate these divisions is, once again, not unique to Baltimore. By one common metric of segregation—the black/white dissimilarity index—Baltimore has above-average segregation, but still short of that in a number of big cities such as Chicago, New York, Atlanta, Philadelphia, D.C., and Boston.

Fourth, inequality is real in Baltimore. Like the young person in the Brookings video said, there are parts of the city where you can walk 5 minutes and find yourself in a completely different community.

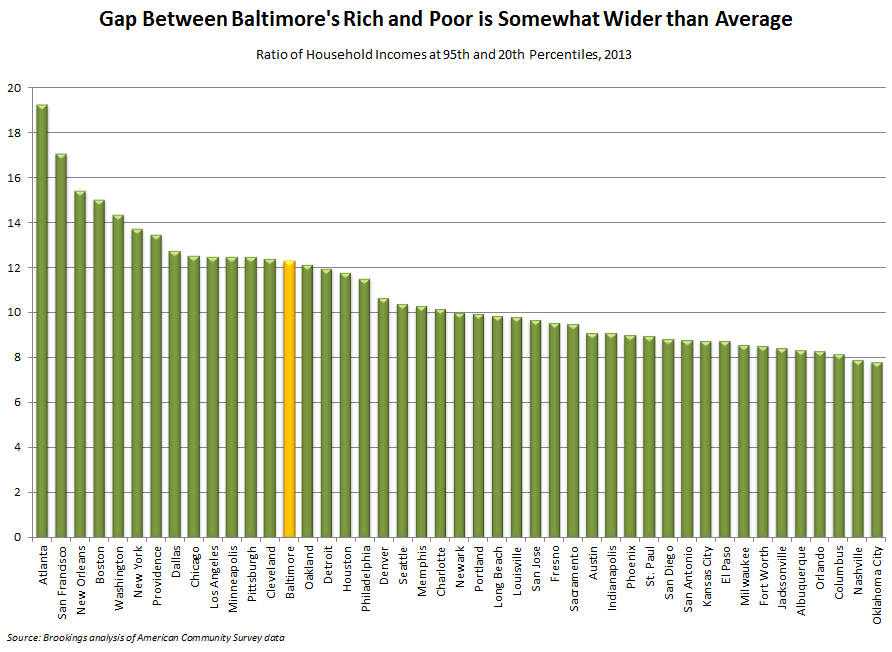

This, too, is the reality in many major American cities today. The typical high-income household in Baltimore earns about 12 times what the typical low-income household does. That gap is 19 in Atlanta, 17 in San Francisco, land of expensive chocolate shops, and 15 in Boston. But by this measure, Baltimore’s inequality also exceeds that in cities like Oakland, Denver, and Seattle.

So yes, Baltimore is an unequal city. It’s a city of low incomes. It’s a segregated city with concentrated poverty. Those are really just another way of saying, Baltimore is an American city.

While none of these factors by itself reveals the true challenges facing Baltimore and its residents, or explains why peaceful demonstrations in April transformed into violent unrest, they add up to something very sobering.

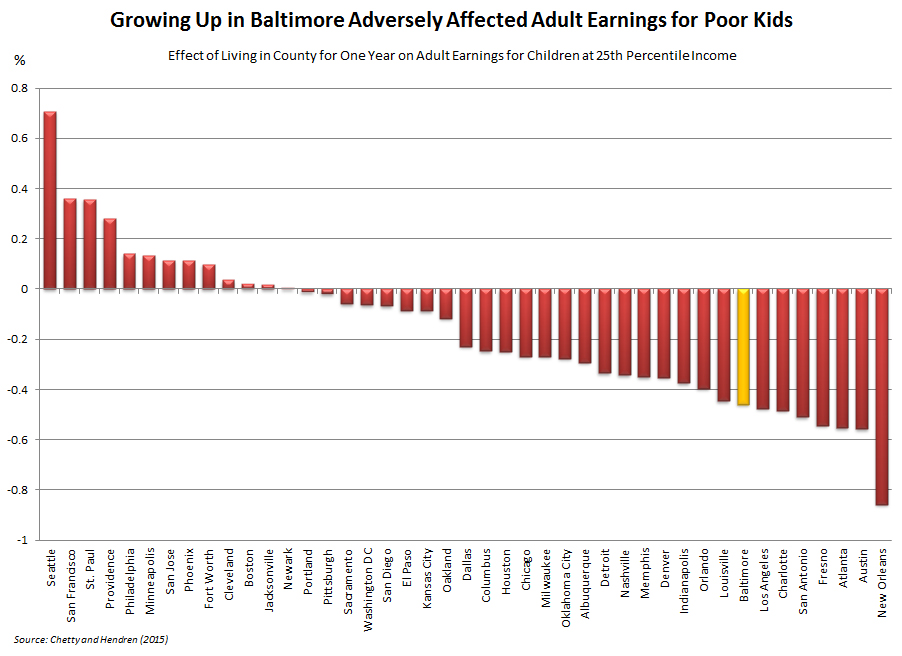

That’s in the final chart displayed here, which is derived from some new groundbreaking research by Raj Chetty, now at Stanford, and Nathaniel Hendren here at Harvard.

Many of you might have seen this research highlighted a few months back in the New York Times, with great maps and storytelling. As a policy wonk really concerned about these issues, I was extremely grateful for the attention it so deservedly got. As a researcher, I was insanely jealous!

Essentially, Chetty and Hendren used IRS data from across 20 years to estimate the impact that growing up in a particular place had on a child’s future earnings.

These data are for the counties surrounding big cities, so they’re not always a perfect representation of city effects, but they clearly revealed that where you live—particularly where you grow up—really does seem to matter for social mobility.

On this measure, the effect of living in Baltimore city on future economic outcomes for poor kids was highly negative, equivalent to reducing their income by about $4,500 a year at age 26. By contrast, growing up in King County, Washington, around Seattle, would raise that individual’s earnings by about $3,000 at that same age.

Again, Baltimore is not off the charts here—you can see even larger negative impacts in New Orleans, Atlanta, and even Los Angeles, for instance.

And it’s important to keep in mind that this is how these cities have affected social mobility for people who are today younger adults. Most cities have changed over the past 20 years in ways that might change mobility prospects for today’s kids. As they say, your results may vary.

But I wanted to highlight these data for a couple reasons.

First, because the researchers behind these estimates find that many of the factors shown in these other charts have direct implications for upward mobility. I realize this is getting super-wonky for late in the evening, but let me quote their study briefly:

“Counties that have higher rates of upward mobility tend to have five characteristics: they have less segregation by income and race, lower levels of income inequality, better schools, lower rates of violent crime, and a larger share of two-parent households.”

Now, I didn’t highlight all of those factors in the charts, but from other research we know that school quality, violent crime, and family formation patterns are themselves influenced by things like segregation, inequality, and concentrated poverty.

And second, I think that promoting upward mobility may be a more helpful, unifying goal for cities to embrace than, for instance, solving inequality.

This is not to say that high inequality doesn’t pose an obstacle to upward mobility. In fact, I just said it did! But really addressing inequality inevitably means doing something about society’s top incomes, whether through industry regulation or taxation, because astronomical growth at the top is truly fueling rising inequality. But that’s really hard to do at a city level.

However, there are many other things that cities—indeed, many of your cities—are doing, and can do, that can make them more effective engines for upward mobility:

– More cities are taking new steps to ensure that their workers are paid wages that help their families meet basic needs and afford a decent home.

– More cities are re-examining their economic development strategies to ensure that the industries and businesses they cultivate provide better jobs accessible to workers with less than a four-year college degree.

– More cities are experimenting with strategies—charters, magnets, new enrollment policies—to give kids from disadvantaged neighborhoods access to better-resourced schools.

– More cities are contemplating inclusionary zoning and promoting mixed-income development to limit exposure to concentrated poverty and keep their places affordable for all.

– In some cases, those cities are part of new region-wide strategies—like the Opportunity Collaborative in Baltimore—to foster growth of mixed-income communities throughout the metro area.

– And more cities are leading or joining collective impact strategies that aim to ensure young people are hitting the key milestones that matter for eventually accessing college and good careers.

That last area is one in which we are hoping Brookings can provide further help and support to cities and their partners.

We are beginning to develop data for a “dashboard” of indicators that show cities and regions how their families and young people are performing on key success factors, such as having a normal birthweight, attaining pre-reading and math skills, graduating high school before childbearing, and gaining a post-secondary degree or a good-paying job.

Eventually, we would like to help places use this sort of “metro mobility model” to target and braid their investments together around the interventions that matter most for local mobility.

This is, of course, tough, long-term stuff, and it’s no substitute for the hard work many of you face in the near term to build or maintain trust between law enforcement and communities. I know you’ll be talking about that tomorrow, too.

But I hope this provides some useful framing for further discussion tonight and tomorrow about the many constructive roles your cities can play in expanding opportunities for all your citizens.

I suspect that the chance to do that was one of the reasons you all got into this business in the first place. I know that my colleagues and I at Brookings are grateful for the chance to help in that regard, too.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Beyond Baltimore: Thoughts on place, race, and opportunity

September 29, 2015