On January 25, Steven Pifer took part in an exchange of views on the U.S. National Security Strategy with the European Parliament’s Subcommittee on Security and Defense. The following is the text of the written statement that he submitted for that session.

Madame Chair, distinguished members of the European Parliament,

Thank you for the invitation to join with Managing Director Hrda and Charge Shub in this exchange of views on the Trump administration’s National Security Strategy. Let me note that I am a nonresident scholar with the Brookings Institution but am appearing here as an individual and do not represent or speak for the Brookings Institution. I will offer four general observations on the National Security Strategy and then more specific comments about how the strategy addresses Europe and the challenge posed by Russia.

General Observations

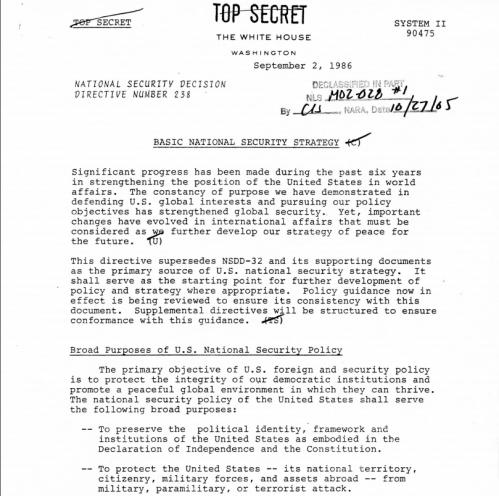

First, the National Security Strategy presents a generally coherent vision of the threats and challenges confronting the United States today and, in whole, a good set of policy recommendations for dealing with those threats and challenges. It largely reflects a mainstream Republican approach to the problems confronting American foreign policy. That is not surprising, given that it was drafted under the supervision of National Security Advisor McMaster and given the policy views of Vice President Pence, Secretary of State Tillerson and Secretary of Defense Mattis.

The authors of the document nevertheless salted the document with phrases undoubtedly designed to appeal to the president: “America first,” “protect the American people,” “promote American prosperity” and “advance American influence.” Such themes and sentiments are natural in a strategy document for America, though such regular repetition may have been aimed as much at the president as at outside readers.

Second, a National Security Strategy outlines, in effect, an administration’s approach to dealing with key foreign and security challenges, offering a world-view and response strategy. But when it comes to individual problems or crises, the National Security Strategy may not always offer the most precise guide to action policy. In nearly 27 years of U.S. government service, I took part in countless interagency meetings on U.S. policy grappling with issues ranging from intermediate-range nuclear missiles in Europe to promoting economic reform in Ukraine to attempting to shape a productive NATO-Russia relationship. I do not recall any meeting in which a U.S. official argued that we had to adopt a certain policy course because of the prescriptions contained in the National Security Strategy.

The third observation builds on the first two and relates to President Donald Trump. It is not clear, at least not to me, that the president instinctively agrees with important elements of his administration’s strategy. The document thus may not give reliable insights into how President Trump might act in certain scenarios.

For example, the National Security Strategy—correctly, in my view—paints a picture of a Russia that has adopted an adversarial approach toward the United States and the West in general, and it outlines some appropriate recommendations in response. However, the description of Russia and the recommendations, like the actual policy that Washington has pursued toward Moscow over the past year, differ significantly from the views that President Trump has expressed regarding Russia over the past several years.

This reinforces my observation that the National Security Strategy may not always be the best guide to how the United States will act in specific situations. The president is the president. The most carefully thought-out and nuanced policy can be overturned by a presidential decision or perhaps even a presidential tweet. And in Mr. Trump, we have a person who believes that unpredictability can be an asset.

I believe that it better serves the U.S. interest when U.S. actions and reactions are predictable. In the large majority of cases, we should want both friends and potential opponents to know what the United States will do and will not do. That is important for assurance of friends and allies, and it is critical for deterring adversaries from aggression or preventing miscalculation. But that may not be the view of the president.

Fourth, the National Security Strategy describes a world of increasing political, economic and military competition among sovereign states. That is a correct assessment given the inter-state challenges posed by countries such as Russia, China, North Korea and Iran, countries that in part seek to revise elements of the existing international order.

The document does not, however, give sufficient weight to the contribution to U.S. and Western security made by the rules-based international order that the United States played a key role in shaping in the aftermath of the Second World War. Institutions such as the United Nations and its specialized agencies, NATO, European Union, Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, International Monetary Fund, World Bank, World Trade Organization, regional trade pacts and others, if imperfect, have nevertheless made substantial contributions to the peace, security and economic development that have greatly benefited the West over the past 70 years.

Maintaining and, where possible, strengthening such institutions would seem to be an obvious response to states that now challenge the current order. But the National Security Strategy does not press that point. One surmise for why it downplays the contribution of such institutions is that Mr. Trump has for many years expressed suspicion about multilateral trade agreements, U.S. alliance relationships and the United Nations. As we saw last year, the Trump administration early on abandoned the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership and Trans-Pacific Partnership, and the president only grudgingly expressed support for Article 5 of the NATO Treaty. I would argue that it is not in the U.S. interest to have the rules for major multilateral trade arrangements written without American participation, or for allies to have doubts about the U.S. commitment to our common security.

Europe and the Challenge Posed by Russia

The National Security Strategy affirms the view that a strong and free Europe is a vital interest of the United States, in part because of shared values. It affirms the U.S. commitment to NATO’s Article 5 and to strengthening deterrence and defense capabilities on the Alliance’s eastern flank, while reiterating Washington’s expectation that allies will meet the goal of raising defense spending to 2% of gross domestic product.

The National Security Strategy calls Russia and China revisionist powers that pose one set of challenges to U.S. and Western security (the other two challenges being the rogue states of North Korea and Iran, and threatening non-state actors). The document describes Russia as seeking to create spheres of influence, to separate America from its allies and partners, and to weaken NATO and the European Union. The strategy notes the Russian military build-up, including modernization of its nuclear capabilities, and the recent Russian efforts, including in cyberspace, to interfere in the domestic politics of other countries and undermine the legitimacy of democratic states. Moscow sees itself in an ongoing competition with the United States and the West and clearly seeks to undo the post-Cold War security order that has developed in Europe.

I share these concerns though, as noted above, little evidence has emerged to suggest that Mr. Trump does, including when he introduced the National Security Strategy. Rather than address the Russian challenge in any detail, the president focused on his desire for partnership relations with Moscow. Many who follow U.S.-Russian relations would like to see better cooperation between the two countries, but that will be difficult without change in problematic Kremlin behavior. Secretary Tillerson clearly recognizes this; he has repeatedly stated that Russia’s aggression against Ukraine presents the single greatest obstacle to moving toward a more positive U.S.-Russia relationship.

The National Security Strategy outlines key pieces of a U.S. response to the Russian challenge. Those pieces include:

- Restoration of military capabilities and readiness, with particular emphasis on modernizing nuclear forces in view of Russian (and other) nuclear force developments (the U.S. National Defense Strategy, released on January 19, makes clear the Pentagon’s priorities now are dealing with long-term strategic competitions with Russia and China). Maintaining robust deterrence and defense capabilities is important. The Department of Defense has high ambitions, though the Pentagon will face constraints from the budget environment in fulfilling those ambitions.

- Upgrading diplomatic capabilities to operate in a more competitive world. This is also important, which is why the current demoralization of and uncertainty within the ranks of the Department of State is so troublesome to former American diplomats.

- Use of economic tools, including sanctions, anti-money-laundering efforts and anti-corruption measures, as means to deter, coerce and constrain adversaries. Congress last year enacted additional sanction mechanisms and strengthened its own role in overseeing sanctions, in part due to a lack of confidence in how the president might deal with sanctions on Russia.

- An enhanced effort to counter cyber and information operations that aim to affect global public opinion. This should include steps to enhance deterrence of such operations in the future. The Kremlin may now believe that the costs that it has suffered for its intrusion into the 2016 U.S. presidential election are bearable; if so, it may well be tempted to interfere in future elections.

The actions described in the National Security Strategy make sense, but the document fails to describe an overarching framework for dealing with Russia. Such an approach should include deterrence, a willingness to push back against the Kremlin’s overreach, for example, in Ukraine, and a readiness to engage in a positive way on issues where U.S. and Russian interests coincide. The latter set of issues should include arms control, though the current U.S.-Russian nuclear arms control regime is at risk, particularly given the uncertain future of the 1987 Intermediate-range Nuclear Forces Treaty.

The strategy does note the importance of forging and sustaining a common approach with Europe. That includes jointly bolstering deterrence and defense capabilities to protect the North Atlantic community. Such cooperation is necessary and strengthens Western diplomacy. For example, U.S.-European collaboration over the past four years in responding to Russia’s seizure of Crimea and its aggression in eastern Ukraine, including the imposition and deepening of sanctions, has sent a message of Western solidarity to Moscow. While these measures may not—at least, not yet—have succeeded in persuading the Kremlin to reverse its actions in Ukraine, they have very likely deterred Russia from even more aggressive steps in the Donbas region.

In closing, the Trump administration’s National Security Strategy has shortcomings but accurately describes the key challenges confronting the United States and the West and lays out actions to take in response. The big question, however, turns on President Trump’s instincts and, to some extent, his volatility. Particularly in a crisis, it is not clear the National Security Strategy would provide a reliable predictor of how he might act.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

TestimonyAssessing the U.S. National Security Strategy

January 25, 2018