Kenyans returning to the polls on August 8 will choose from a multitude of candidates that are seeking offices from president to governor, and parliament to county assembly. This is Kenya’s sixth set of national elections since the end of the one-party state in 1991, and second since the introduction of a new constitution in 2010.

The elections in this economic and political hub for East Africa fall a decade after the worst electoral clashes in Kenyan history, when more than 1,100 people were killed and 650,000 displaced. Given this history and rising political tensions, many fear the potential for violence ahead. While the incumbent President Uhuru Kenyatta is presently favored, regionalism and ethnic divisions continue to overshadow important electoral concerns over economic development, regional security, and political change.

On July 21, the Africa Security Initiative of the Center for 21st Century Security and Intelligence at Brookings hosted an event focused on Kenya and the upcoming elections there. Panelists included Matt Carotenuto of St. Lawrence University, Lauren Ploch Blanchard of Congressional Research Service, and John Tomaszewski of the International Republican Institute. Michael O’Hanlon, Brookings senior fellow, moderated the discussion.

History lingers

Carotenuo offered a historical framework to understand the upcoming elections, noting in particular that this year is the 60th anniversary of Kenya’s national electoral process. He briefly explained Kenya’s road to democracy: The country was ruled by one political party from its independence in 1963 until 2002, with only two presidents taking office during the 40-year period. That period’s autocratic rule set a precedent for national-level politics and elite politicians controlling the national scene through the politics of regionalism, as well as through selective use of government assistance to reward supporters and punish opposition communities.

Carotenuto suggested it was that period which set the tone for the power of the presidency in Kenya, which has since been a very contested political issue and is again at play in the coming election. He highlighted that the 2017 election is the second election since adoption of the 2010 constitution by national referendum, which sought to check executive power as it attempted to distribute much of the centralized power into 47 new counties.

Both leading presidential candidates, Uhuru Kenyatta and Ralia Odinga, are well known throughout the country, Carotenuto said. As sons of Kenya’s first president and vice president, they are leading members of political dynasties. Partly due to their popularity and experience in Kenyan politics, the race is tight, he added. Kenyatta is running on his record as president and a promise of big development projects in the future. His focus is on economic growth and regional security issues. Alternately, Carotenuto continued, Odinga is positioning himself as a candidate for change, thinking about government accountability and making this a referendum on the 2010 constitution and efforts to implement that fully.

Voting patterns

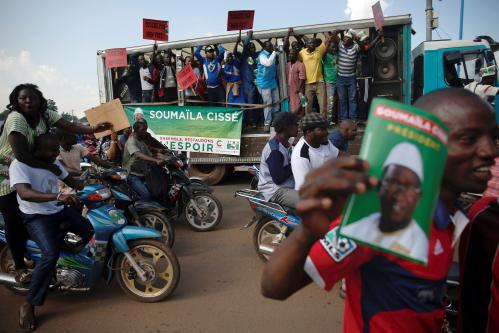

Ploch Blanchard went in-depth on identity politics and explained how Kenyatta and the Jubilee Party have largely controlled Kenyan resources. She highlighted that there is a recent trend of ethnic parties combining to create coalitions. These coalitions have been changing alliances in recent years. In the 2017 election, she said, the National Super Alliance party coalition is seeking their turn at presidential power in ways similar to 2002, the only other time an opposition coalition has won a national election.

There is also the question of to what extent Kenyans will vote along identity and ethnic lines in the upcoming election. Carotenuto noted that an incumbent has never lost an election at a presidential level in Kenyan history. However, in this election cycle, many well-known incumbents at the parliamentary or county level have lost primary races, showing a break with the top-down voting patterns of the past. Moving forward in 2017, he added, this election will highlight the importance of the governor positions, shining light on the local level candidates as well as the presidential race.

Enter: The United States

Tomaszewski talked about a number of U.S. organizations in Kenya that will be monitoring the upcoming vote, including the National Democratic Institute and the Carter Center. In addition, the media has a very important role in how the election will take shape, he argued, saying there is evidence from the 2013 election that there was a significant amount of media focused on peace and self-censorship. Tomaszewski contended that U.S. assistance should be more long-term and strategic, noting that starting an electoral assistance program 18 months prior to an election is too late.

O’Hanlon asked to what extent the United States can improve the prospects for Kenya before and/or after the election?

Carotenuto stressed that there is insecurity in northeastern regions of Kenya that are being overlooked, and these areas need to be included in future security initiatives. The United States supports the Kenyan involvement in Somalia, as Somali-based terrorist group al-Shabab continues to threaten the northern regions of the country. In addition, he argued, the regional security aspect should continue to be a part of U.S. involvement, as Kenya is home to nearly 500,000 refugees from regional conflict and famine zones.

Kenya is also one of the largest recipients of U.S. foreign and military assistance, Carotenuto pointed out. It is considered a regional hub for transportation and finance in East Africa. Blanchard pointed out that Kenya has one of the most progressive constitutions, vibrant civil societies, and among the freest media on the continent. Despite this, the opposition party is at times repeating claims that the ruling party is planning to rig the upcoming election, and the Jubilee party has been indicating that voting for the opposition is voting for violence. Blanchard noted that there are also evidence of an uptick in hate speech—while it tends to be more personal than ethnic, it can spill over to the latter domains.

Blanchard explained that in many ways, Kenya is a good news story in terms of democracy, and stressed that a peaceful and credible election is important. She argued that the United States and other countries should focus on those goals, along with supporting institutional capacity—particularly in county assemblies and governor offices—as well as strengthening the judiciary. Additionally, she said that thinking about the role of the election and what it means for the broader East African region is important.

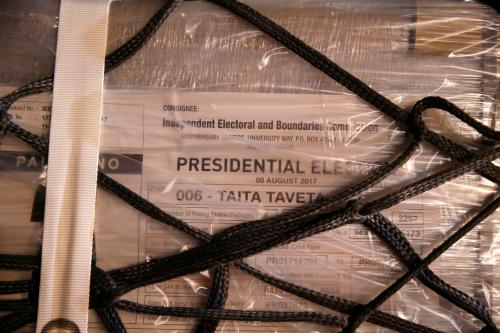

Tomaszewski concluded with mention of the liberating prospect for youth and women in this election. He noted that there are over 14,000 candidates running for around 1,800 seats. There are good signs for an engaged population as Kenyans hope for a peaceful and credible election. The Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC) has made many reforms since 2013 in order to prepare for the coming vote. There are 362,000 poll workers that need to be trained and must be able to comprehend the electoral process to contribute to a credible election.

Emily Terry, an intern with the Center for 21st Century Security and Intelligence, contributed to this post.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

As Kenyans head to the polls, here’s what’s at stake

July 27, 2017