Over the last 12 months, Africa’s democratic trajectory has been extremely volatile, ranging from protests in Eswatini (Swaziland) demanding an end to the country’s absolute monarchy, a peaceful turnover of power in Zambia, and a military coup in Sudan that undercut the country’s fragile political transition.

In 2022, developments in three key countries—Angola, Kenya, and Senegal—will provide an important bellwether for where the continent is heading. All three countries face important local and national elections. The outcome of these elections will significantly impact prospects for reversing democratic erosion, the extent to which civil society and countervailing institutions can keep leaders accountable, and the future range of tactics that incumbents employ to retain power.

Senegal’s local elections: The battle for Dakar

On January 23, 2022, Senegalese will vote for mayors across the country’s 550 municipalities. Current mayors, almost all of whom belong to the Benno Bokk Yakaar (BBY) party coalition of President Macky Sall, have been in office since 2014 and legally should have served only five-year terms. However, municipal elections originally scheduled for June 2019 have been postponed four times.

The upcoming local elections are important for several reasons. First, they are a referendum on Sall’s presidency, which has tainted the country’s democratic credentials in recent years. In fact, Freedom House recently identified Senegal as backsliding from a “fully free” to a “partly free” regime. This downgrade is partially due to changes to electoral laws that Sall’s government implemented in 2018 to limit eligibility criteria in the 2019 presidential elections, concerns that he will violate the constitution and run for a third term, and his repeated interference in the judiciary to ensure prosecutions of popular opposition leaders. Over the last several years, such prosecutions have targeted former government minister Karim Wade, former Dakar mayor Khalifa Sall, and parliamentarian Ousmane Sonko. Large-scale street protests in both March and November 2021 against the arrests of opposition leaders were extremely violent, leading to the deaths of at least 10 people and prompting fears concerning the degree of conflict that might surround the January polls. Approximately 20 opposition parties have now coalesced under the Yewwi Askan Wi (“Liberate the People” in Wolof) coalition, led by Sonko, to vie for municipal control.

Second, the upcoming elections will determine who leads Dakar, the country’s capital city, which has remained an opposition stronghold since 2009. The city is fiercely contested because it houses a quarter of the country’s population, produces 55 percent of national GDP, and generates 80 percent of the country’s employment opportunities. The BBY’s Dakar mayoral candidate is Abdoulaye Diouf Sarr, who is also the current minister of health, while his main competitor is Barthélémy Dias of the Yewwi Askan Wi. Due to disenchantment among young Dakarois with the incumbent regime’s corruption and inability to generate employment, Dias is likely to triumph in a fair contest.

Third and relatedly, the independence of the National Autonomous Electoral Commission (CENA), which oversees all municipal elections, has been under question since all of the CENA’s members are appointed by the president. In addition, the requirement that mayoral candidates pay CFA 15,000,000 (around $25,000) to be eligible competitors has fueled ongoing debates about the monetization of Senegalese politics. Consequently, the outcome of the municipal elections will likely have a significant impact on how Senegalese view the fairness of their country’s electoral processes, including the forthcoming legislative contest scheduled later in 2022.

Angola’s presidential elections: Test for an ambivalent reformer

In contrast to Senegal, Angola has long been viewed as an autocratic, one-party state. On December 10, 2021, the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA)—which has ruled Angola for 46 years—confirmed that the incumbent president, João Lourenço, will again be the party’s candidate in the August 2022 presidential elections. Lourenço came to power in 2017 amid much fanfare and anticipation about greater political liberalization after decades of control by his predecessor, José dos Santos. Just like the incumbent BBY in Senegal, the MPLA will confront in 2022 a newly formed opposition coalition known as the United Patriotic Front, led by Costa Junior of the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA).

In the 2017 elections, Lourenço campaigned on a platform of combating corruption, ending nepotism, and diversifying Angola’s economy away from its dependence on oil and diamond revenues. After his inauguration, he recovered $3 billion stolen from the country’s sovereign wealth fund and fired the former president’s daughter, Isabel Dos Santos, as chair of the state oil company, Sonangol, for money laundering. Lourenço also passed several decrees that prohibited exclusive ownership of businesses by particular families. Yet, given the dense network of clientelist ties within the MPLA, critics allege he has limited his anti-corruption drive to mostly family members and allies of former President Dos Santos.

Although Lourenço initially allowed greater political openness, including more media freedoms, his government has encountered public criticism on multiple fronts. Foremost are citizens’ economic grievances caused by 30 percent food price inflation and a public debt-to-GDP ratio of 135 percent that has diverted revenue from spending on social programs to debt servicing. In addition, he introduced a controversial electoral bill in September 2021 requiring that the counting of votes be done centrally rather than at the level of each municipality and province, which would have allowed for greater civil society oversight. The MPLA-dominated parliament supported the bill while also rejecting the opposition’s demand for biometric identification of voters to mitigate the possibility of voter fraud. In contravention of the 2010 constitution, he also has postponed local elections at least three times, prompting UNITA to suggest that the delay is due to the MPLA’s fears of losing control of major cities to the opposition. In the meantime, the president continues to appoint all mayors. These and related decisions have resulted in several large-scale anti-government protests in 2021, many of which were brutally suppressed by security forces, which fired live bullets into crowds.

These developments cast doubt on Lourenço’s ability to win in free and fair elections. Indeed, UNITA accuses the government of freezing its bank accounts as well as hacking its phones and messaging apps. State media outlets have reverted to partisan reporting while several private ones have been closed down, preventing the opposition from delivering its message to voters.

Kenya’s general elections: Clash of the Titans

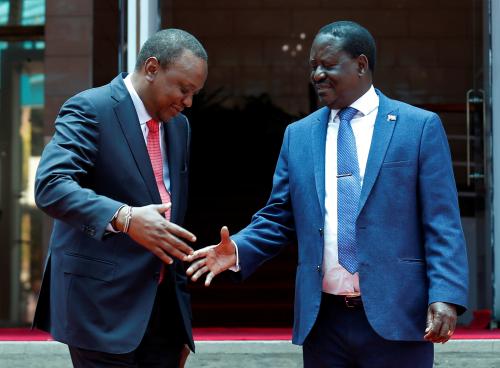

Earlier this month, Kenyan opposition leader Raila Odinga launched his fifth bid for the presidency. However, the ongoing soap opera among political elites in the run-up to the country’s August 9, 2022 general elections has been unfolding over several years. In 2018, President Uhuru Kenyatta, leader of the Jubilee Party, reconciled with Odinga via a symbolic handshake after their intensely heated 2017 electoral contest. Thereafter, the two politicians launched the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI), which was designed to introduce a range of institutional reforms. These included amending the constitution to allow for power sharing between the president and a prime minister, abolishing parliamentary approval of presidential appointees, and appointing a regulator to oversee the judiciary. Kenyatta and Odinga claimed that the reforms would significantly reduce ethnic divisions, foster interparty unity, and enhance peaceful coexistence. However, Kenyatta’s deputy president, William Ruto, argued that if the BBI reforms were implemented, it would render the country’s political system less democratic and exacerbate the country’s ethnic divisions. Ultimately, Kenya’s High Court declared the BBI unconstitutional, and Ruto’s opposition cemented the growing acrimony between him and Kenyatta, further propelling the latter’s support for Odinga rather than Ruto as his successor when Kenyatta’s term ends next year.

Ruto and Odinga—who were allies in the 2007 elections—are now separately mobilizing monetary and electoral support for their campaigns. Odinga has folded his Orange Democratic Movement into a larger One Kenya Alliance encompassing many other political leaders. In a country where complex patronage networks are important determinants of electoral outcomes, Odinga has been courting the country’s oligarchs, known as the Mount Kenya Clan, who are wealthy business financiers with substantial clout among Kikuyu voters in Central Kenya. Odinga, an ethnic Luo, needs support in that region to realistically defeat Ruto. Ruto, who remains deputy president of Kenya, quit the ruling Jubilee Party and formed the United Deputy Party earlier this year. Despite being one of the wealthiest people in the country, he is mobilizing the poor and unemployed by portraying himself as an average “hustler” who started out selling chickens in his youth.

As an early sign of concern about voter apathy, few eligible citizens participated in the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission’s (IEBC) mass voter registration exercise in October 2021. Some Kenyans claimed they were unwilling to register due to allegations that the IEBC oversaw electoral malpractice during the 2017 elections under the leadership of the IEBC’s chairman, Wafula Chebukati, who continues to retain his position. Given Kenya’s recent history of violent and contested polls, this will likely be one of the coming year’s most intensely watched elections.

Conclusion

Senegal, Angola, and Kenya all participated in President Biden’s much-debated Democracy Summit in early December 2021. Along with many of the forthcoming programs envisioned in the Summit’s $424.4 million Presidential Initiative for Democratic Renewal, the experiences of the three countries highlight the need to bolster independent institutions, particularly electoral bodies and the judiciary, as well as campaign finance reforms that diversify participation and mitigate patronage. Such efforts are paramount for dissuading citizens in Africa—and elsewhere—from either apathetic disengagement or destabilizing violence as well as for enhancing confidence in the legitimacy of elections as a genuine mechanism to foster democratization.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

African democracy in 2022: 3 elections to watch

December 29, 2021