Editor’s Note: As part of this year’s U.S.-Islamic World Forum, many of our participants are writing posts on Markaz to share their thoughts on one of the diverse topics discussed at the Forum beginning tomorrow in Doha, Qatar. We hope you will join us by watching live webcasts or following the conversation on Twitter with #USIslam15.

During the past two years, the early optimism about the Arab uprisings, especially prevalent in the months after the fall of Hosni Mubarak in Egypt in 2011, has given way to considerable pessimism about the region. Certainly, the violent eruptions in Libya, Syria, and Yemen, and the continued conflict in Iraq especially with the rise of ISIS, have been part of this gloomy picture. But much of the pessimism is driven by a sense of deep sectarianism or religious fanaticism that have seemingly been on the rise. This picture however fails to take note of the fluidity of identity in the region, which is highly influenced by groups’ interactions with each other and with the outside world. One of the fascinating examples of this is the initial expansion of cosmopolitan identity in the Arab world in the early months after the start of the Arab uprisings.

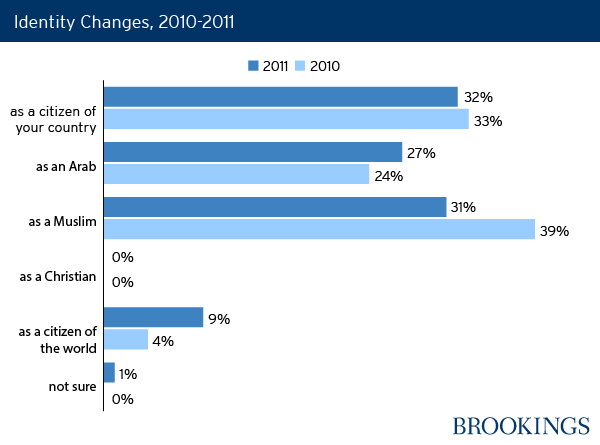

While failed states and weaker central authorities have forced not only fragmentation but also turning to local, tribal, familial, and sectarian identities, the simultaneous expansion of communications across groups and across state boundaries has created new opportunities for bolstering more encompassing identities. In public opinion analysis of six Arab states (Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Jordan, Lebanon, and the United Arab Emirates), there was a visible increase in the number of people who identified themselves as “citizens of the world” above other identities in October 2011, over the entire preceding decade during which Islamic identity was on the rise and cosmopolitan identity was negligible (only 1-4 percent of the public favored “citizen of the world” over other identities.

About nine months after Mubarak’s overthrow, Egyptians who identified themselves as “citizens of the world” (over Muslim, Arab, or Egyptian) increased from 2 percent to 9 percent. There was a similar increase over the entire sample of six Arab countries:

What explains this increase? Generally, what are the dynamics that expand or shrink pluralism in the Middle East? To kick off the conversation, I have co-authored (with Katayoun Kishi) a discussion paper that relies on data analysis and other thoughts that will be distributed among participants. The paper attempts to show that identity selection is dynamic and can only be understood as a function of relationships and of the assessment of prospects of these relationships.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

As conversations focus on sectarianism, a panel explores pluralism in the Arab world

May 31, 2015