As the Trump administration surpasses 100 days in office, President Donald Trump’s approach to allies and partners around the world has been a subject of significant debate. To his supporters, Trump is implementing long-overdue efforts to ensure greater burden-sharing and less dependence on America for other countries’ security. To his detractors, Trump’s approach is transactional, chaotic, and a drain on American influence in the world. One thing virtually all observers agree upon is that Trump’s approach to alliances represents a break from long-standing American foreign policy.

To help assess the impacts of Trump’s approach, the Brookings Global China project convened four foreign policy experts with differing viewpoints and backgrounds to answer a series of questions on America’s alliances: Doug Bandow, Brian Blankenship, Mireya Solís, and Thomas Wright. They addressed the following questions: First, is the U.S. alliance network a strategic asset or a burden in its competition with China? Second, can the United States outcompete China economically while escalating trade disputes with its allies? And third, will the Trump administration’s skepticism toward U.S. alliances and security guarantees push allies closer to China or toward independent defense strategies?

The contributors agree that alliances matter—but disagree on how. Some warn that the rapid deterioration of alliance coordination is eroding deterrence and economic resilience, setting back the United States in its competition with China. Others argue that pulling back from overextended commitments could reduce the United States’ risk of entrapment and push allies to carry more of the burden. Their written correspondence is below.

Alliances: A benefit or burden?

Do America’s global security commitments enhance deterrence or hinder its ability to respond flexibly to the threats posed by China?Doug Bandow

Paradoxically, Washington’s alliances simultaneously extend its reach while diminishing America’s security. In a military conflict with the People’s Republic of China (PRC), allies would increase U.S. firepower—if they joined Washington against Beijing. However, if they did not, since doing so would risk short-term pain and long-term enmity, the alliances would offer Americans only an illusion of security.

Worse, such defense guarantees expand U.S. commitments beyond U.S. interests. For instance, the desire to safeguard Japan’s and the Philippines’ independence does not warrant a commitment to battle the PRC over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands or such geographic oddities as Mischief Reef. Seventy-two years after the conclusion of the Korean War, the Republic of Korea, which vastly outranges its northern antagonist, should be able to stand on its own, at least in conventional terms. There is no need for the United States to garrison the South, which could lead to a clash with China as well as North Korea.

It would be better for Washington to maintain a cooperative relationship with friendly states, focused on enhancing their self-defense capabilities. The United States could also coordinate with them on shared interests elsewhere. However, Washington should limit its military involvement to combatting direct threats to its most important, even vital, interests.

Brian Blankenship

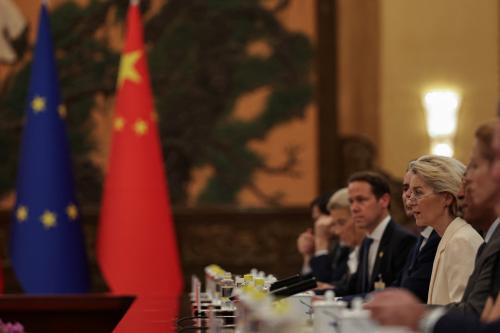

The extent to which the U.S. alliance network is a net asset in Sino-American competition is likely to vary based on three factors: region, the level of U.S. commitment, and the level of shared interests. U.S. alliances in the Indo-Pacific more naturally lend themselves to deterring China than those in Europe, as Indo-Pacific countries can more directly contribute to frontline defense by supplying their own military power and hosting American forces. By contrast, the value that NATO and European allies offer for U.S.-China competition is primarily, though not exclusively, economic. U.S. sanctions on China in the event of war in East Asia will be more punishing with European participation. More broadly, the alliance may offer some leverage to encourage Europe to reduce its trade with China.

The net value of the U.S. alliance network in Europe for U.S.-China competition, then, depends on whether Europe assumes primary responsibility for the continent’s defense, Europe’s willingness to restrict trade with China, and whether that willingness is conditional upon the level of U.S. commitment to NATO. By contrast, if the United States diverts a considerable portion of its scarce resources to Europe rather than the Indo-Pacific, or if Europe is ultimately unwilling to restrict trade with China, then the contribution of U.S. alliances in Europe to Sino-American competition is less.

Mireya Solís

The U.S. alliance network undergirds the projection of American power abroad and is an essential asset in the U.S. competition with China. There are substantial advantages conferred by these security partnerships: overseas basing to boost U.S. in-theater presence, joint industrial defense development, intelligence sharing, and diplomatic alignment, among others. The track record of U.S. alliances in delivering stability and strengthening deterrence is robust. Russian President Vladimir Putin has not dared attack a NATO ally, and China has refrained from using military force against U.S. allies in Asia, even as it has stepped up its coercive tactics in the East and South China Seas.

Testament to the clout of American alliances is how much U.S. rivals chafe at them and seek their erosion.

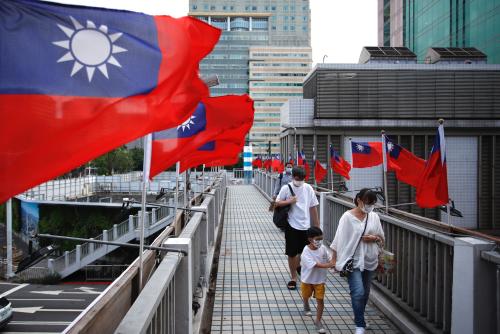

Testament to the clout of American alliances is how much U.S. rivals chafe at them and seek their erosion. Beijing has sought to drive a wedge between the United States and its allies, but until recently, it seemed further away from achieving this objective. The U.S. alliance network deepened and expanded in notable ways in response to concerns over the destabilizing actions of revisionist powers (including China’s support of Russia’s aggression). Japan and the United States embarked on the most ambitious effort to modernize the alliance’s command-and-control structure. South Korea and the United States deepened consultations on nuclear deterrence. And the Philippines expanded U.S. access to military bases. Moreover, the traditional hub-and-spoke system of bilateral alliances was supplemented with new partnerships such as AUKUS—between Australia, the U.K., and the United States—and the U.S.-Japan-South Korea trilateral.

But the world has gyrated in the past three months with the return of alliance-skeptic Trump to the White House. Beijing will try to capitalize on this strategic space.

Thomas Wright

The U.S. alliance system is America’s primary strategic advantage over the PRC, and Beijing knows it. It’s not just that the alliances in the Indo-Pacific help shape the strategic environment around the PRC in ways that disincentivize aggression; it’s also the effect of a global network of alliances. Europe’s coordination with the United States on the Indo-Pacific and the Gulf states moderating their outreach to the PRC under pressure from Washington are two examples. This alliance system tends to get stronger in tough times, not weaker. Thus, every time the PRC does something assertive or provocative, it has generally led to a deepening of cooperation between the United States and its allies. Examples include the U.S.-Philippines Enhanced Cooperation and Defense Agreement and the U.S.-Japan-South Korea trilateral. This helps constrain the PRC and provides U.S. officials with viable options to constructively shape the regional order, increase U.S. influence, and respond to PRC provocations.

Trade disputes with China and U.S. allies

Can the United States outcompete China economically while escalating trade disputes with its allies?Doug Bandow

Although the United States could best China even while waging economic war on its allies—the United States is likely to outperform China due to its higher economic productivity and freer, less regulated economy—America would be more likely to succeed with better policies in place and friends alongside. The United States has several important economic advantages, but they are rooted in open competition and international engagement. Irrespective of relations with Beijing, it is in America’s interest to preserve a vibrant international marketplace. Shifting toward a policy of autarky-light will diminish America’s innovativeness and economic growth.

Imposing widespread trade barriers also makes systematic global retaliation likely. As the president recently discovered, his demand that other nations not retaliate fell flat. The resulting economic chaos triggered stock and bond market crashes and diminished international confidence in the U.S. economy and dollar. This process has reduced America’s economic advantage over the PRC, encouraging governments and investors worldwide to look elsewhere for financial security.

Moreover, if Washington hopes to constrain Chinese economic growth and ultimately restrict the PRC’s international role, Americans should work with European and Asian friends rather than against them. In recent years, the United States has won sometimes reluctant foreign cooperation against Beijing. Trump’s hostile attitude and policies threaten to disrupt that process, having created an opening for increased European and other foreign cooperation with China.

Brian Blankenship

The United States’ and China’s ability to thrive economically despite their bilateral trade war will depend in large part on whether they can find other markets for their exports and substitutes for their imports. But the United States’ escalating trade disputes with the rest of the world at the same time as it engages in a trade war with China run counter to this objective and could make outcompeting China and mitigating the United States’ pain from the trade war more difficult. To the extent Washington closes its market to foreign goods, its allies will search for other export markets. Their retaliatory efforts will, in turn, make importing from non-U.S. sources more attractive. These developments could push U.S. allies into a corner in which they become more likely to strike trade deals with China that they might otherwise be reluctant to make, such as over imports of Chinese electric vehicles. This would ultimately undercut the United States’ ability to outcompete China by throwing Beijing a lifeline while Washington simultaneously closes itself off from the rest of the world.

Mireya Solís

Working with allies and partners is indispensable for the United States to outcompete China by nurturing advanced manufacturing ecosystems, guarding sensitive dual-use technologies, stabilizing access to critical minerals, strengthening supply chains through diversification, and fighting Chinese overcapacity and other unfair trading practices. To build cutting-edge semiconductor fabs and battery plants, the United States needs to attract leading firms that are headquartered in partner countries. Preventing China from accessing advanced technology requires allied nations to enforce U.S. restrictions and align their export control practices with Washington’s. And coordination is essential if the United States wants to combat the transshipment of Chinese products via third parties and develop alternative sources of rare earths to ease China’s control over this chokepoint.

Trump’s trade disputes with allies compromise these goals. Three adverse dynamics are at play. First, there is a crisis of confidence about the U.S. ability to competently steward the world economy due to the erratic imposition and suspension of sweeping tariffs. Second, the tariffs have led to the self-inflicted weakening of the United States and its allies, both as the specter of stagflation grows in the United States and trade-dependent Asian partners brace for recession if the tariffs are not lifted. Third, Trump’s actions have led to a loss of trust in advancing cooperation on reducing overdependence on China and strengthening economic security. Quite simply, a trade coalition focused on the China challenge cannot be built while treating allies as economic rivals.

In sum, the United States is less prepared to lead, and U.S. allies are less willing to follow.

Outcompeting China does not mean having a higher rate of GDP growth or balanced trade. It means gaining and sustaining an advantage in the industries that will define the future and reducing our exposure to the PRC in areas vital to our national security.

Thomas Wright

The short answer is no. Waging a global trade war makes America weaker, hurts the free world more generally, and gives China more leverage with other countries, economically and diplomatically. It also allows Beijing to portray itself as the champion of the multilateral economic order, which is ridiculous when one considers how much China has done to undermine and destroy that order over the past decade through its non-market practices. It’s also important to remember that outcompeting China does not really mean having a higher rate of GDP growth, and it definitely does not mean balanced trade. It means gaining and sustaining an advantage in the industries that will define the future, such as artificial intelligence and clean technology, and reducing our exposure to the PRC in areas vital to our national security. Achieving that entails investment at home, for example, through the CHIPS and Science Act, which Trump has attacked. It also requires collaboration with allies and partners to create an ecosystem that provides resilient supply chains, coordinated investments in key technologies, and cooperation on targeted export controls.

The consequences of U.S. skepticism toward allies

Will the Trump administration’s skepticism toward U.S. alliances and security guarantees push allies closer to China or toward independent defense strategies?Doug Bandow

The global order is shifting irrespective of U.S. intentions and policies. Although America remains the world’s most powerful nation, its ability to coerce recalcitrant states is diminishing. Trump discovered this uncomfortable truth only weeks into his second term. Moreover, the price of attempting to dictate to other states is increasing among rising powers, such as India.

Most importantly, Washington’s ability to maintain military dominance in every region against ever more powerful challengers is ebbing. Today, in “normal” times, absent a hot war, pandemic, or financial crisis, publicly held U.S. debt is near 100% of GDP, approaching the historic post-World War II level. Washington is running $2 trillion deficits and spending more than $1 trillion on interest annually. America’s commitment to the defense of allied states is almost certain to decrease, perhaps dramatically, in the coming years.

Although U.S. allies could choose to bandwagon with the PRC, they are more likely to balance against threatening powers, in this case, China. That is the more common historical behavior. Moreover, Washington’s friends include significant powers, democratic, prosperous, and independent. While Cambodia might be willing to trade away its sovereignty, not so Japan, Australia, and South Korea, which are able to resist Chinese pressure.

Countries like Vietnam and Indonesia, though less committed to the West, also are likely to jealously guard their sovereignty. Indeed, in Asia, Beijing’s increasing aggressiveness has encouraged disparate states, including Japan and India, to cooperate in resisting Chinese encroachments. U.S. retrenchment seems more likely to encourage swifter rearmament by Japan and other states than retreat.

Brian Blankenship

The most probable outcome is that allies hedge. Allies that are worried about Chinese power and behavior will likely remain so regardless of whether they perceive the United States as a credible security provider. Nevertheless, given China’s size, military power, and importance as a trade partner, few countries will be eager to confront it. As a result, U.S. allies are likely to selectively accommodate China while also taking steps to hedge through independent military arming and cooperation with third parties.

Allies that are worried about Chinese power and behavior will likely remain so regardless of whether they perceive the United States as a credible security provider.

Allies’ willingness to balance against China will likely depend as much on China’s actions as on those of the United States. The more aggressively Beijing behaves in maritime disputes with its neighbors, for example, the more urgently they will seek to counterbalance it. Similarly, China’s alignment with Russia will complicate its ability to cultivate closer ties with Europe.

Nevertheless, efforts to counterbalance China without the United States are likely to be plagued by challenges. Historically, balancing coalitions have often been quite slow to form due to each state’s temptation to free ride in the hope that other countries will bear the costs of confronting, deterring, and ultimately fighting a revisionist power.

The risk that disengagement from U.S. security guarantees would lead allies to free ride or even bandwagon with China is likely to be greater among smaller states that are less capable of resisting China on their own. Similarly, U.S. trade restrictions are likely to render allies more dependent on trade with China and thus more vulnerable to its economic coercion.

Mireya Solís

U.S. allies in Europe and Asia have not (yet) reached the conclusion that a post-alliance “Plan B” will better serve their national interests. But neither can they make confident predictions that an “America First” administration will honor U.S. security guarantees. While the strain is more visible in the transatlantic alliance, the disquiet in Asia is unmistakable. Asian allies and partners have been watching a split screen. On one side, senior members of the administration, like Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, have sent reassurances that alliances are highly prized in the pursuit of strategic competition with China. On the other side, Trump accuses friends of free-riding and expects the United States to be paid for protection services. Leaders in Asia are laser-focused on his side of the screen.

In responding to growing uncertainty about the U.S. role, Asian allies have not executed a full pivot to China, nor have they endorsed overtly independent defense strategies. Rather, hedging has become more prominent, which has involved proof of value to the United States (contributions to the alliance on defense, investment, and technology) and stabilization of relations with China. Beijing has been receptive, fearing isolation from escalating tensions with the United States, but the rapprochement can only go so far. China’s contributions to regional instability loom large, and Beijing has not persuaded U.S. allies to partake in a joint response to Trump’s tariffs.

In the long term, however, strategic shifts may be afoot with a sharper focus on enhanced strategic autonomy. U.S. partners may see the acquisition of new military capabilities, the control over supply chain chokepoints, and the cultivation of economic groupings and security partnerships that bypass the United States as cards they need to hold in dealing with an inconstant ally.

Thomas Wright

America’s allies are generally skeptical of China because of China’s behavior, not because they are doing Washington a favor. Just look at Europe. European countries worry that China’s overcapacity poses a major challenge to their domestic industries. They are also concerned about overreliance on China for critical materials and foundational technologies, and they believe that the PRC’s support for Russia hurts their national security interests. None of this changes just because Trump is trashing the transatlantic alliance. That said, the United States and Europe can more effectively deal with China if they work together—on economics, critical materials, technology, and security. Since the Trump administration seems to have little interest in really deepening the alliances, it means that the United States and Europe will be less effective in protecting their interests against China’s problematic behavior. It’s also probably true that a weaker transatlantic alliance will empower voices in Europe that favor more engagement with Beijing. Finally, I would just note an irony that China’s best friend amongst European leaders is probably also its most pro-Trump leader—Viktor Orbán. If the Trump administration wants to force Europe to choose between the United States and China, it could start with Hungary.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Are America’s alliances a source of strength or a burden as it competes with China?

A written Q&A on the value of America's alliances

May 15, 2025