Despite popular rhetoric, migration is an economic boon, especially for Europe’s aging and shrinking populations. Indeed, some recent discussions of migration have been much ado about nothing. But emigration is also speeding the population decline in some poorer Eastern European countries, bringing tough challenges for them. In a recent paper, we aim to challenge some popular misperceptions toward Romanian migrants and ask: what is needed to attract these migrants to return?

Western European economies needs migrants

To minimize the negative impacts of an aging and shrinking population and sustain actual and potential economic growth, Western European countries need young economic migrants. And lots of them. But the idea of more economic migrants at a time of continued fallout from the 2008 crisis in the Eurozone is not universally popular and support for nationalist parties has increased sharply in much of Western Europe. Many of these nationalist parties and parts of the media prey on the perceptions people have of foreigners in general. For example in early 2014 the most popular U.K. national paper, The Daily Mail, ran with a story that 29 million Bulgarians and Romanians could move to the United Kingdom—more than the entire population of the two countries!

The underlying misconception behind these exaggerations is that migrants contribute little to society. Yet, recent work has found that Polish children in U.K. schools help to raise the performance of native-born students. The same goes for the many young and well-educated Romanian migrants who contribute to society, working in healthcare, banking or even football, rather than the common stereotype of Romanians being a huge drain on the taxpayer. This is in line with recent findings by the OECD, which suggest that migrants tend to be net contributors to the public purse and fill important job roles that natives are unable to fill. We can expect something similar from migrants who came from the Middle East, Africa, or Central Asia. As the Economist recently noted, “people who cross deserts and stormy seas to get to Europe are unlikely to be slackers when they arrive.”

But Eastern European countries face their own declining populations

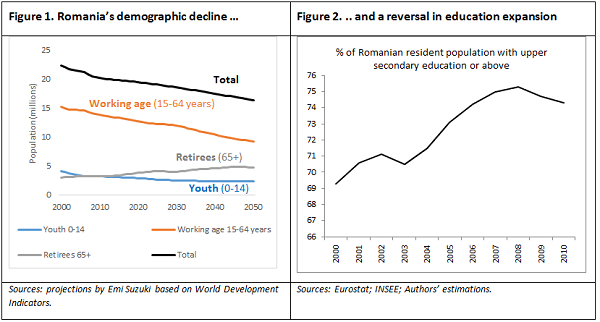

While Western European countries benefit from the inflow of young, motivated people, migrants’ home countries may find it challenging to cope with their loss. Romania faces its own population crisis, with the population falling from close to 22 million in 2000 to just 19 million today—a fall of 14 percent—and the fall is particularly steep among working age adults (Figure 1). Much of this is due to the number of migrants leaving, but the challenge is even greater since those who are leaving tend to be younger and better educated than the rest of the population. In recent years, this has resulted in a reversal in previous educational gains in Romania (Figure 2). A declining population brings challenges linked to growth, inflation, and financing pensions and healthcare. An aging population brings similar challenges, as Japan has found. One way to reverse the decline might be to attract back those who left and who have gained new skills and experiences while overseas.

Under which conditions might migrants choose return to their home country?

Better economic prospects in home countries remains the key variable to attract migrants to return back home. For example, Romanians who expect to earn good wages at home and Romanians who are confident enough to maintain business links with their home country are more likely to consider returning to Romania. Policies that boost productivity (and therefore wages) as well as policies that improve the business climate would therefore encourage Romanian migrants to return to Romania, increasing the skill stock of the Romanian labor force. The good news is that policies that achieve this are beneficial more generally. The bad news is that many countries struggle with these basic good policies.

One country that has succeeded in attracting back its migrants is Poland. Poles left in large numbers after Poland joined the European Union in 2004. But they also returned during the financial crisis, leaving Western Europe and returning to Poland—the only EU country to escape recession during the crisis years. When migrants leave they take their skills with them, and stop contributing to their host lands (as the U.S. states of Georgia and Alabama recently found, with hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of crops going to rot as migrant crack-downs reduced agricultural workers). But this proved to be a boon for Poland; when former emigrants returned they helped to sustain a growing economy by investing earnings—for example, in new businesses—and bringing the new skills learned abroad home.

This blog draws on evidence from: Hinks, T. and S. Davies (2015), “Intentions to return: evidence from Romanian migrants”, World Bank Working Paper Series, WPS7166.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

A tale of attracting emigrants to return home

September 22, 2015