While Labor Day weekend may be behind us, this week has offered ample evidence that Washington and the rest of the nation will be focused on jobs through fall, the 2012 election cycle, and beyond.

Last night, President Obama gave a televised address to Congress in which he offered an array of proposals intended to boost employment. Federal Reserve Board Chair Ben Bernanke also gave a speech on the economy earlier in the day. Understandably, both men focused on the aftermath of the recent recession and financial crisis, but in so doing, both Bernanke’s description of our current employment problems and the president’s prescription for getting out of them neglected a longer-term issue that goes back to the last recession, in 2001. We have had a slack labor market for a decade.

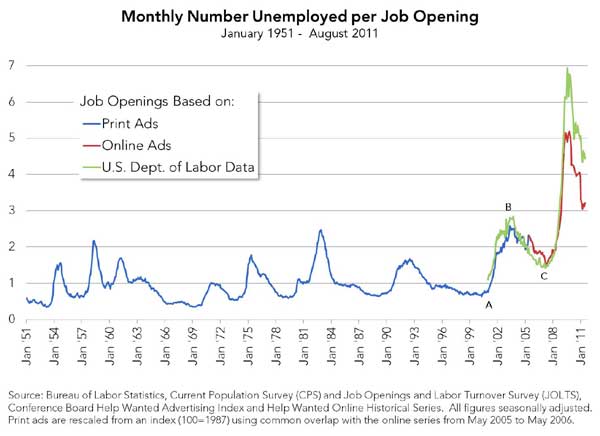

Job opening and unemployment data released in recent weeks paint a stark picture of just how tough it is out there for those looking for work. There are somewhere between three and five out-of-work job-seeking Americans competing for each job opening. As shown in the chart below, competition for jobs among the unemployed remains greater than any time before the financial crisis, stretching back to the Great Depression.

From 1951 through 2007, there were never more than three unemployed workers for each job opening, and it was rare for that figure even to hit two-to-one. In contrast, there have been more than three jobseekers per opening in every single month since September 2008. The ratio peaked somewhere between five-to-one and seven-to-one in mid-2009. It has since declined but we have far to go before we return to “normal” levels.

The bleak outlook for jobseekers has three immediate sources. The sharp deterioration beginning in early 2007 is the most dramatic feature of the above chart (the rise in job scarcity after point C in the chart, the steepness of which depends on the data source used). But two less obvious factors predated the recession. The first is the steepness of the rise in job scarcity during the previous recession in 2001 (from point A to point B), which rivaled that during the deep downturn of the early 1980s. The second is the failure between 2003 and 2007 of jobs per jobseeker to recover from the 2001 recession (the failure of point C to fall back to point A).

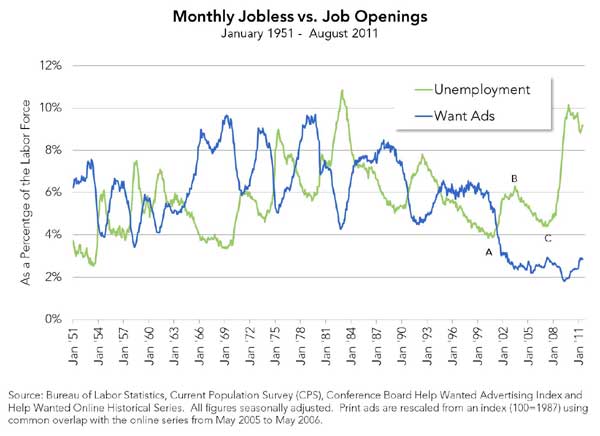

The next chart shows trends in job openings and in unemployment separately to tease out the dynamics in play.

Unemployment increased during the 2001 recession, but it subsequently fell almost to its previous low (from point A to B and then back to C). In contrast, job openings plummeted—much more sharply than unemployment rose—and then failed to recover. In previous recoveries, openings eventually outnumbered job seekers (where a rising blue line crosses a falling green line), but during the last recovery a labor shortage never emerged.

The anemic recovery was followed in 2007 by an increase in unemployment to levels not seen since the early 1980s (the rise after point C). However, job openings fell only a little—and then recovered. The recession did not reduce hiring; it just dumped a lot more people into an already weak labor market.

The result is a shortfall in demand for workers unprecedented in the lifetimes of essentially everyone working today.

The patterns in these charts have multiple and complex root causes. Princeton economist Alan Blinder and others have pointed to off-shoring as a source of downward pressure on domestic hiring. Researchers such as M.I.T. economist David Autor instead emphasize technological change and the automation of routine work. Our recent history of financial crises suggests that asset bubbles may be a third factor. Businesses overinvested during the dot-com boom that peaked in early 2000, holding back further investment in the recovery that followed and dampening labor demand. The Fed’s efforts to spur business investment through low interest rates ended up just facilitating the inflation of the housing bubble, the bursting of which was behind the recession that closed out the decade. A final potential factor is that national and state innovation policies may be outmoded in the new economy, failing to promote efficient investment in businesses and sectors that would expand hiring.

Whatever the causes, the evidence is clear that the health of labor markets were compromised well before the recession. President Obama’s proposals—including tax incentives for businesses to hire the unemployed and spending increases and tax cuts to boost consumer demand—or ones like them may breathe life into the recovery and return us to the calmer days of 2007. But if the patterns of the last decade prevail, slack labor markets will continue to leave unemployment levels higher—and wages lower—than they need to be.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

A Decade of Slack Labor Markets

September 9, 2011