The changing nature of office work and the persistent U.S. housing crisis are motivating local government officials and the owners of underutilized office buildings to convert offices into housing. However, the economics of such conversion projects are more complex than the economics of ground-up development; both asset holders and the public sector, therefore, need good baseline information and analytical frameworks to understand the costs and benefits of conversion and how sensitive these factors are to policy influence.

This report builds on past work including six case studies of varying office and housing markets across the United States to understand the financial feasibility of conversion and the role of public policy in shaping such projects’ financial feasibility. In each of these six case studies, we identified three real office buildings as candidates for office-to-residential conversion. The analysis examined the physical characteristics of each building and the architectural feasibility of conversion, producing a hypothetical housing unit “yield.”

This publication is part of a broader series examining the potential of office-to-residential conversions across six U.S. case studies. The project is part of a cooperative agreement with the US Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the research team is composed of contributors from Gensler, HR&A Advisors, Brookings, and Eckholm Studios.

In this report, we build on that previous analysis to explore the financial implications of conversion. For any given building, an owner makes the decision to convert (or not) in response to his or her assessment of the building’s future business prospects, its tenants, the financing partners needed for any required investment, and the regulatory environment. For each owner, this decision is sensitive to many variables and is dependent on judgments that are not likely to be transparent to outside observers.

This report offers a generalized model of the financial component of decisionmaking about office-to-residential conversion, and then it illustrates how the model works using the example of the Railway Exchange Building, a vacant office building in downtown St. Louis. The report applies the model to 18 buildings, three for each of the six case study markets where we previously explored the architectural feasibility of converting. This allows us to compare buildings, and more importantly it lets us illustrate the ways in which policy levers impact the financial viability of conversion projects. In five out of six markets, we conclude that no office-to-residential conversion projects were economically viable without public policy intervention. However, we also show that public policies can influence conversion economics, and we present a sensitivity analysis of possible policy interventions using the Railway Exchange Building as an example.

Analytical framework and methods

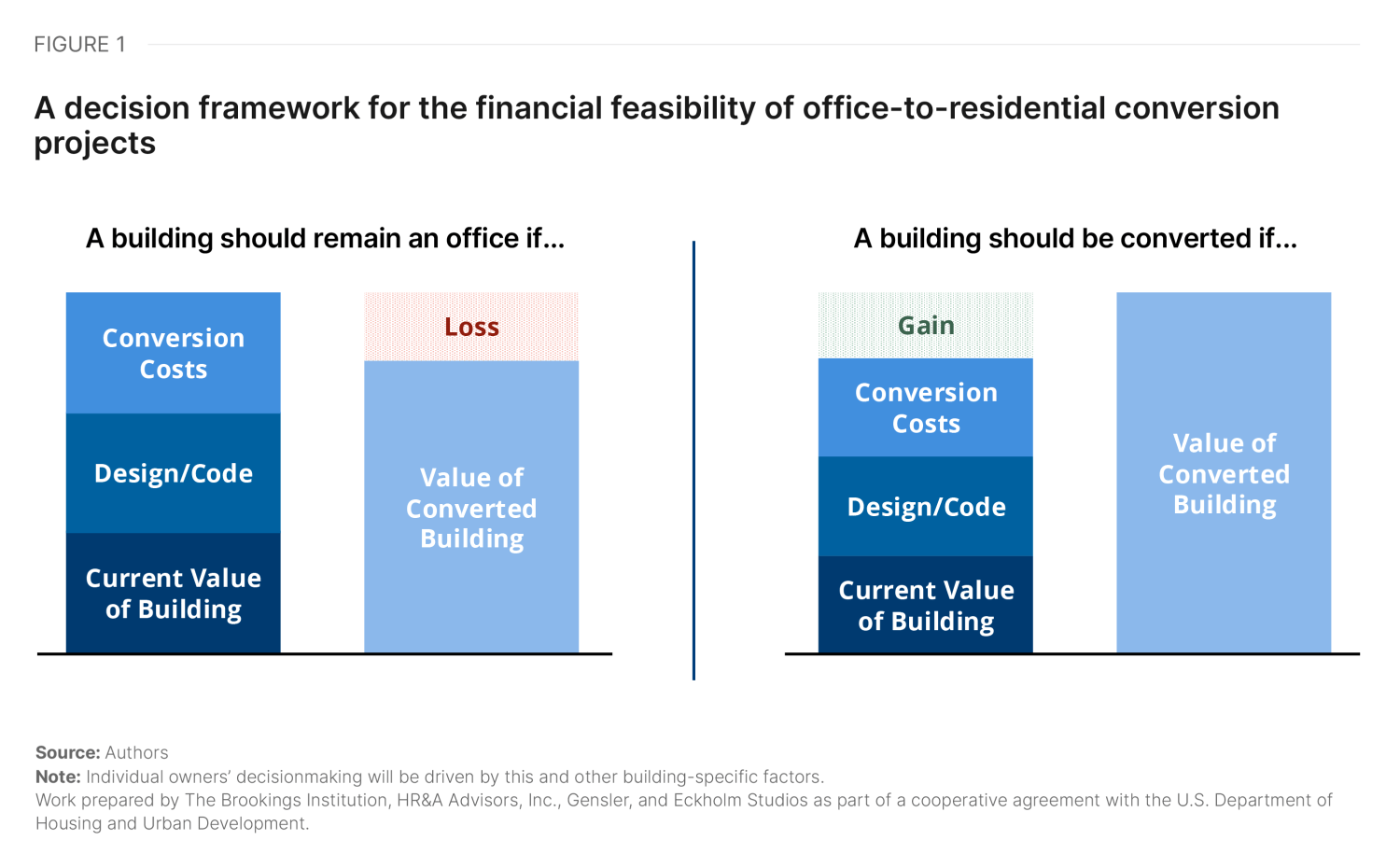

Underperforming office buildings face two potential paths forward: to remain an office building or to be converted into a residential building. We define the value of an office building as the net present value (NPV) of the building’s future cash flows, assuming that it remains an office building, and the value of the potential residential building as the NPV of the future cash flows of the building if it were converted to residential use. We account for the fact that the residential cash flows can only be achieved after paying the cost of conversion (including design, construction, and financing costs) by subtracting estimates of these costs from the residential building’s NPV. Similarly, if a building were to be maintained for office use, we assume that some level of capital investment would be necessary to attract new tenants, and these costs again are subtracted from the value of future cash flows to determine the building’s NPV. We can then compare the office and residential NPVs for a given building to see which option maximizes value.

This decision framework is outlined below in Figure 1. The feasibility gap is any gap between the cost of production of a housing unit, relative to the value of that unit on the open market (through rent or sales proceeds).

Financial model

Our financial model uses market data from each of the case-study cities and applies it to three representative buildings in each market to develop cash flow figures for the two scenarios for each building: a scenario for continued office use and one for a residential conversion. The residential conversion cash-flow scenario factors in the cost to acquire, empty, and convert a given building. The model then calculates the NPV of each scenario. The model also creates a stabilized-year pro forma for the conversion, and it identifies the net financial gap or surplus, which is defined as the capitalized value of the converted residential building minus the cost to convert and the capitalized value of the existing office building.

In evaluating these policy scenarios, readers need to know the following four terms:

- Net operating income (NOI): NOI consists of a building’s annual financial profits, calculated as rental income minus operating expenses and property taxes (excluding debt service).

- Net present value (NPV): NPV is a common metric to establish the value of a building. It can be calculated based on the sale price of comparable buildings, or as a function of NOI. This analysis relies on the latter approach.

- Capitalization rate (or cap rate): A building’s cap rate is established by calculating its NOI divided by NPV. Cap rates reflect the investment market’s perception of an asset’s risk and, therefore, vary by real estate market and by building class (office versus residential).

- Return on cost: A project’s NOI in the first year as a share of the costs of converting the project.

We use return on cost as a metric to determine a project’s financial feasibility for the stabilized- year pro forma analysis. Return on cost is calculated as the NOI of a converted building divided by the costs to convert including acquisition, lease terminations, hard costs (such as labor and materials), soft costs (such as design, permits, and legal fees), and financing.

Both NPV and return on cost may be used as metrics to compare the returns of a building under two different investment scenarios. For cases in which two investment options (for either office or residential use) would have similar timing, return on cost is the preferred means of comparing a developer’s returns. This might be the case, for instance, if a project’s cost outlays in either scenario were incurred in year 1 and if the project would have zero returns until year 4 either way. For cases in which the two investment structures diverge, however, return on cost is a suboptimal means to compare investment scenarios. Investment structures could differ, for example, if a nonconverted building were to continue to operate as an office space in years 1–10, whereas a residential conversion would incur cost outlays in year 1 and achieve zero returns until, say, year 4. A ten-year NPV, in contrast to return on cost, allows for two varying patterns of investments and returns, and it aggregates the cumulative values of both scenarios over a longer timeframe. This analysis, therefore, relies on NPV for comparing office scenarios to residential conversion scenarios. When evaluating the potential for incentives to increase the feasibility of conversion projects, the analysis uses return on cost to evaluate a conversion scenario without incentives compared to a conversion with incentives.

A given building’s acquisition costs, for the purpose of modeling a return-on-cost metric, are calculated as the NOI in year 1 divided by the capitalization rate, rather than a ten-year NPV.

This model takes a high-level, typological approach with the goal of understanding the likely outcome for a given building typology, while it also acknowledges that real buildings have unique ownership situations, financing, and other characteristics that could impact the feasibility of conversion. When there is a financial gap, the pro forma identifies the subsidy amount required to convert the building.

Market assumptions

Table 1 summarizes the assumptions used for financial modeling in each of the six cities. Assumptions about rent, vacancy, operating expenses, cap rates, and rent growth are sourced from CoStar market data collected in the third quarter of 2024. Turner Construction developed cost estimates for each building conversion, providing building-specific inputs for the financial model. Assumptions for expense growth, loan-to-cost ratios, and interest rates are based on author estimates, which we then validated through interviews with local stakeholders including building owners, brokers, and public sector officials in each of the six cities.

For example, the Railway Exchange Building in St. Louis is a fully vacant, 1.1 million-square-foot office tower that was completed in 1913. After private developers failed multiple times to renovate it, the city is now purchasing and converting the building. However, the conversion is expected to cost up to $400 million (in hard and soft costs), assuming that the city gives a developer the land and the existing building for free.

Because St. Louis has a weak downtown residential market with average rents of $2.19 per square foot for new construction and average vacancy rates of 22%, the converted building—which would produce more than 780 new units—would only achieve a 2.71% return on cost. We assume that a conversion would need to achieve a return on cost of at least 100 basis points more than the residential cap rate (that is, a return on cost of 8.3% compared to a cap rate of 7.3%) on an untrended basis to justify the risk of conversion. The spread is based on conversations with conversion developers in markets around the country.

Findings

Each case study included speculative conversion studies of three buildings from each of the six downtowns, generating 18 sample conversion projects. In all six of the downtowns studied, the average square footage of residential space was found to be more profitable than the equivalent average square footage of office space, even when allowing for lower residential efficiencies. Yet most of the profiled buildings were found to be financially infeasible to convert under base-case financial constraints.

Figure 2 below displays the NPV of a residential conversion project for each of the 18 buildings profiled for this study, under assumptions of average residential rents for each respective downtown, 95% apartment occupancy, and no incentives. As Figure 2 illustrates, 16 of the 18 sample buildings would have a negative NPV after factoring in the costs to convert, even though switching the buildings to residential use would generate considerable revenue increases. Given the predominance of negatively valued buildings in Figure 2, office-to-residential conversion projects remain financially challenging in downtowns across the country. Yet the analysis also illustrates both (a) a heterogeneity of potential outcomes for office buildings within a single downtown and (b) meaningful differences in conversion feasibility between the downtowns studied.

Put simply, conversion projects remain expensive, and for the overwhelming majority of the buildings studied, the costs of conversion exceed the value captured from converting them to residential use. While residential rents in some markets have grown more quickly than office rents over the past five years, local demand for the types of residential units that would be created through conversion projects in the six downtowns profiled is generally insufficient to recoup the costs of converting the office spaces modeled for this analysis. In the six markets, the average hard cost of conversion across each city’s three profiled office buildings was more than $300 per square foot in all cities except Houston. As a result, the feasibility of converting such office buildings is largely a function of having a critical mass of renters willing to pay enough to live in a given downtown to cover the high hard costs of conversion.

Sensitivity analysis of market assumptions and policy interventions

For the Railway Exchange Building in St. Louis, without any policy interventions, the resulting 2.71% return on cost would be well below the 7.3% market cap rate (reaching a threshold of 100 basis points higher than that would require an 8.3% return on cost). Even though the 2.71% return figure is positive, it indicates that the certainty of returns is too low to justify conversion. However, this conclusion is based on many assumptions, so we modeled the sensitivity of this result to key assumptions about housing demand. In all cases, the converted building has a negative NPV (see Table 2).

We also modeled the sensitivity of the calculations to policy interventions that change the input assumptions. For example, the Railway Exchange Building is eligible for federal and state historic tax credits. These programs provide a tax credit of 45% of the construction cost per square foot. These credits are either kept by the developer, or they are often sold to a third party, with the proceeds from the sale used to offset the cost of the building. In this case, those tax credits produce the equivalent of $135 per square foot, which effectively reduces the development cost by more than one third.

St. Louis also has additional local financial incentives available on a discretionary basis to such projects. We considered the impact of both an abatement of local real estate property taxes and a low-interest loan (which either government or philanthropic sources can provide) to reduce the interest expenses of the building’s construction. Table 3 shows how these incentives change the development cost assumptions: the left side of the chart represents “baseline” assumptions, while the right side illustrates potential changes due to policy intervention.

Finally, cities can help offer potential increases in the revenue associated with residential conversion through investments in neighborhood amenities that increase the rents that converted units can feasibly command. For example, the City of St. Louis could invest in the downtown public realm to support the residential market and enable higher rents and lower vacancy rates. For instance, Ballpark Village, a mixed-use downtown neighborhood surrounding the St. Louis Cardinals’ Busch Stadium, achieves rents of roughly $3.25 per square foot, which could be attainable for the Railway Exchange Building with substantial investment in the public realm to increase the desirability of living on that side of downtown St. Louis.

These three policies target all three of the general incentive categories discussed in these case studies: they can reduce the construction costs of the property (through historic tax credits), lower the operating costs of the property (through local tax abatements), and increase the revenue associated with the residential conversion (though investments in amenities that would increase rents).

We repeated our sensitivity analysis with an updated range of rent assumptions (see Table 4). Together, these incentives and investments could push the estimated return on cost for the Railway Exchange Building to 8.44%, which is 114 basis points above the local residential cap rate. By this metric, a developer may find the conversion project worthwhile. However, using a ten-year NPV, the project essentially breaks even; the conversion has a ten-year NPV of -$1 with incentives, a vast improvement from the -$204 figure without incentives, but this result essentially amounts to a net profit of zero.

Limitations

The per-square-foot cost estimates for converting a range of buildings across our case study areas were very high. This may be because most of the buildings we selected would be challenging to convert. However, it is also possible that different design decisions, in part based on different insights about what renters want from apartments or greater building code flexibility, could significantly reduce the cost of conversion. In our interviews with developers, the lowest cost of a recent conversion that we encountered was $145 per square foot, which is less than half of the median cost estimate in our sample of 18 buildings. Because office-to-residential conversion is a relatively niche development skill, it is possible that one source of high costs is a lack of private and public sector experience with such projects, not infeasibility in an absolute sense. In addition, full-scale design of buildings and systems often allows building owners to identify areas of efficiency that would not be clear from the high-level analysis here.

Financial feasibility is only a part of building owners’ decisionmaking process when they are deciding whether to convert an office building. In markets like Pittsburgh, where this model estimates that all three of the profiled buildings are not financially feasible for conversion, the market nevertheless has a track record of successful office conversion projects. Conversely, the owners of buildings that model as financially feasible for conversion may have other reasons not to convert them. We believe that there are three reasons for this.

- Financial feasibility analyses look at one point in time. Past conversion projects happened at different times and in different financial contexts compared to now, and factors such as costs of construction and borrowing may have been more favorable when past projects occurred. Los Angeles, for instance, has a track record of conversion projects under the Citywide Adaptive Reuse Ordinance over the past two decades. However, at the time of this study, the high hard costs of conversion rendered all three buildings profiled in the city as financially unfeasible.

- The building typologies we have looked at tend to be larger office buildings that are more expensive to convert and that have lower efficiencies as residential buildings, compared to other buildings that have already been converted (typically, older and smaller ones).

- Building owners’ decisionmaking is motivated by financial and non-financial factors that are not accessible to outside analysis. Policy tools may affect some of these factors, but not all of them.

Beyond the physical and financial feasibility of conversion projects, other factors may influence an owner’s decision to convert or not, including the following ones.

Factor 1: An owner’s basis for a building, which refers to his or her original acquisition price and/or level of investment in a building. A building that may have been purchased a long time ago may have a significantly lower basis than a building acquired or invested in more recently, and such differences would influence an owner’s expectation of returns. As illustrated in Figure 1, one of the key components of the feasibility analysis is an assessment of the “current value of a building.” This figure is often established by each owner, based on a mix of accounting, outside debt obligations, or other calculations that are opaque to outside observers. Shifts in underlying value can happen rapidly and in ways that are not clear to other parties.

Factor 2: An owner’s willingness to reduce operating losses—in a scenario where an office building is running extreme deficits and conversion would help reduce, but not eliminate, these deficits, office owners may justifiably be unmoved by the prospect of conversion.

Factor 3: Subjective reasons, such as the personal importance of a building or a market for a building owner,which may inform an owner’s motivation to invest or refrain from investing in a building or a market, in contradiction of the outcome of a financial feasibility analysis.

Recommendations

As with all significant real estate investments, the financial considerations of office-to-residential conversion projects involve a dynamic interplay between local market forces that affect demand for different types of real estate, macroeconomic trends that influence the cost of goods and capital, and private developers’ appetite for the investments and risks associated with significant construction projects.

However, we can also see from the analysis of the buildings and the cities in this study that public financial tools, when applied thoughtfully, can dramatically reshape the feasibility of a given project and can be powerful levers in sustaining the health of an area experiencing low utilization of existing office spaces. Yet as powerful as these tools can be, they carry financial and administrative costs, and they, therefore, should be subject to a critical and holistic understanding of the tradeoffs between costs and benefits across a range of interventions.

As local, state, and federal policymakers consider the future of financial policies associated with office-to-residential conversation, they should focus on the following key lessons from our research.

- Existing policy intervention tools, particularly those that are relatively straightforward to access, can be extremely impactful. Historic tax credit programs are by far the most consistent financial tool identified in our case studies. While they only apply to older buildings, these programs are relatively predictable to access and provide a significant reduction in project costs, while also helping an area to retain the fabric of its historic buildings. As new policies are developed, this example provides a template for the types of clear, predictable, and impactful programs that provide maximum impact.

- Locally tailored programs that focus on reduced taxes are also very powerful and can be an important opportunity to realize local policy goals. The financial analysis shows that these programs can dramatically reduce the costs of building and/or operating a conversion project, and they, therefore, have the potential to move a project from infeasible to feasible and to create benefits such as affordable units. In addition to being accessible by right, these programs need to be tailored to a given area’s local fiscal environment to ensure that there is alignment between the entity assessing the taxes (property or sales taxes), the policy goals being addressed, and the financial impact on the project’s pro forma. At the same time, these programs should be understood as investments of public resources; as such, they produce a range of direct and indirect benefits and should be undertaken and evaluated according to that range of benefits.

- Finally, the financial feasibility of conversion projects needs to be understood in the context of local housing markets and the ways that those markets are influenced by public investments in a given building’s surrounding environment. While many of the financial tools for the public sector associated with office-to-residential conversion focus on reducing the costs of individual project transactions, the other side of the balance sheet is just as important. Successful public investments in infrastructure (such as public transit), facilities (such as schools and libraries), and public realm improvements (such as open spaces and retail corridors) all significantly influence the value of a given market. These types of investments can increase the feasibility of conversion (by increasing the likely value of the new units), while also providing broader and more lasting benefits to an entire community.

The financial analysis presented here shows that there are multiple potential policy levers to address the financial feasibility of conversion projects. Collectively, the question of which financial tools are “right” for a given community is best answered by the needs of that community and by the financial and legal constraints that shape which tools may be applied. In addition, tools to kickstart a local conversion market may not be required at the same level over time, as local developers gain experience in reducing hard costs and as residential demand strengthens. As these local debates unfold, the most productive outcomes will emerge from processes that include the full range of tools, a thorough consideration of a given community’s holistic needs, and a multifaceted assessment of the potential long-term benefits of such conversions.

-

Acknowledgements and disclosures

The authors would like to thank the following members of the HR&A Advisors team for their assistance in developing this piece: Paul Silvern (Partner), Stefan Korfmacher (Research Analyst), and Clark Ricciardelli (formerly HR&A), who is now a Real Estate Development Analyst at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In addition, the authors thank Ben McAdams for his review of a draft of this piece. Any errors or omissions are those of the authors.

The work that provided the basis for this publication was supported by funding under an award with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. The substance and findings of the work are dedicated to the public. The authors and the publisher are solely responsible for the accuracy of the statements and interpretations contained in this publication. Such interpretations do not necessarily reflect the views of the Government.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).