The following case study details the recent efforts and future plans of CenterState CEO and the Central New York Community Foundation (CNYCF)—a closely linked pair of organizations working together to extend and deepen the impact of Micron Technology’s proposed $100 billion investment in semiconductor fabrication plants over the next two decades. Key takeaways for regional civic and philanthropic leaders include:

- CenterState CEO, an economic development organization, and CNYCF are establishing a complementary relationship wherein CenterState CEO and the state pull resources into the region and ensure they are aligned with strategy, while CNYCF pushes those resources as deep into the community as possible. This has required a wide range of actors to orient in a shared strategy through formal processes.

- CNYCF and others will need to invest in capacity-building so that small, community-based organizations can contribute to a fast-moving mega-project. This will require CNYCF to not only strengthen individual nonprofits, but also its own ability to assemble and manage teams of organizations that each play a specific role as part of an integrated solution (e.g., for workforce development).

- While there is arguably adequate funding for workforce and small business development efforts related to the Micron project, the region does not currently have the resources needed to boost housing development or other forms of infrastructure (including child care and health care). This requires CenterState CEO to play a new role in mobilizing new resources, and for CNYCF to leverage its impact investing tools.

The case study series

Between 2021 and 2022, the federal government passed major legislation authorizing nearly $4 trillion in economic investment, including $80 billion in place-based industrial policy. Brookings has been tracking these investments, including the early implementation of coalition-based grants aimed at advancing key national priorities such as national security and economic and technological competitiveness.

This case study is part of a report series that goes beyond the programmatic efforts catalyzed by these investments to examine the underlying civic infrastructure that regions have begun to build—and will ultimately need to sustain in the long term—to support resilient, inclusive, and innovation-driven economies.

The main report details five functions that regions need, with a particular focus on the unique role of local philanthropy in supporting these functions, both as funders and strategic partners. The five functions are:

- Connect networks and build trust among increasingly disconnected economic actors, including business leaders, community organizations, students, and entrepreneurs.

- Orient regional stakeholders toward a shared understanding of the economy and the pathways to inclusive growth.

- Activate key business leaders to inform, engage, and invest in strategic regional inclusive growth efforts.

- Integrate teams of diverse, complementary organizations to solve specific, high-priority challenges using evidence-based interventions.

- Mobilize resources through sustainable financial models to maintain momentum, using performance measurement tools to identify the highest-priority areas for investment.

The five case studies—Chicago/Illinois; Fresno, Calif.; New Orleans; Syracuse, N.Y.; and Tulsa, Okla.—illustrate how these functions and the philanthropic leadership that enables them play out on the ground. Each region has received different forms of federal funding under the 117th Congress, and also varies in size, geography, and maturity of economic and workforce development ecosystems—thus offering lessons for a range of philanthropic and civic leaders across the country.

Background

Syracuse, N.Y.’s economic story is a familiar one. Its strategic location along the Erie Canal helped it thrive during the first industrial revolution. Its economy later diversified in the second industrial revolution, most notably yielding a specialization in radar technology, which took the form of a GE research park that employed 17,000 workers. But in the 1970s, Syracuse’s manufacturing sector started to decline. By 2020, there were almost 80,000 fewer residents in the city than during its peak in 1950. Racial disparities were large and growing. In the decade from 2013 to 2023, the Syracuse metro area ranked 55th out of 56 large metro areas for job growth and 38th for the decrease in the poverty rate.

While the region’s economic story is unfortunately ordinary among older industrial cities, over the past 15 years, the region and state made extraordinary investments in economic development strategy. Micron’s investment, the shared commitment to ensuring that it spurs inclusive growth, and the shared theory about how to make that happen are all results of the groundwork that was laid during this time.

Strategy development and implementation in the Syracuse region is largely led by CenterState CEO, a business-led nonprofit, in close partnership with Empire State Development (ESD), a public benefit corporation that acts as the state’s economic development agency. CenterState CEO was created in 2010 through a merger of the region’s two business membership organizations. This consolidation, paired with ESD’s active support of CenterState CEO (as well as its peer organizations in other regions), means that Syracuse has a more obvious “center of gravity” for regional strategy than exists in most regions. CenterState CEO’s position has been strengthened by investments from philanthropies such as the Allyn Family Foundation, which have provided it the flexible staff resources needed to sense and seize strategic opportunities.

To an unusual degree, CenterState CEO’s strategy pursues inclusion and innovation as mutually reinforcing objectives. Many of its peer organizations now frame their work in these terms, but have not meaningfully expanded action into these domains. In contrast, CenterState CEO both operates incubator and accelerator programs and runs an in-house inclusive workforce development operation as part of a broader “racial impact and social equity” portfolio. This approach was developed and formalized in part through several high-profile strategic planning processes that preceded the industrial policy moment, including ESD’s Upstate Revitalization Initiative (approximately $50 million awarded for drone research and development and testing infrastructure from 2015 to 2020) and the JPMorgan Chase AdvancingCities Challenge ($3 million).

New York state, meanwhile, was separately making major investments to bolster its competitiveness in the semiconductor sector: billions in the Albany NanoTech Complex, a semiconductor research and development facility, and billions more in business attraction incentives for new semiconductor projects such as GlobalFoundries’ $4.2 billion chip fabrication plant near Albany in 2009 and Wolfspeed’s $1 billion facility in Utica (50 miles east of Syracuse) in 2019.

As a result of these efforts, at the beginning of 2022, Syracuse had an extraordinarily well-connected set of community, regional, and state actors who were capable of aligning around economic and workforce development efforts. By the end of 2022, this community-region-state coalition turned its attention to securing federal investments. The process was fast, and the effects were dramatic.

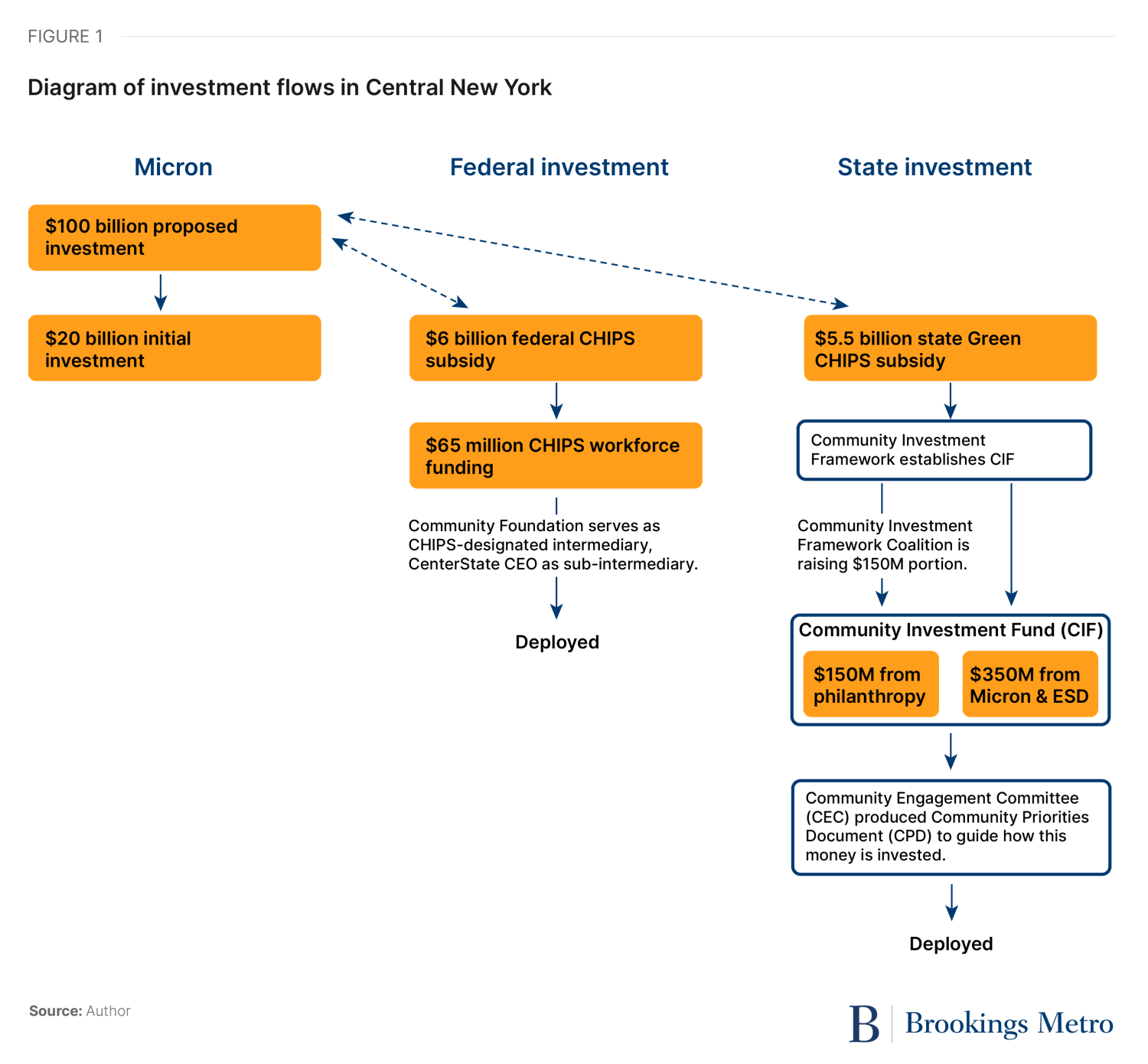

The CHIPS and Science Act was signed in August 2022, establishing a 25% tax credit, a $39 billion fund to incentivize domestic production, and $13 billion for research and development and workforce efforts. Two days later, the state’s Green CHIPS legislation was signed, providing additional incentives contingent on firms meeting labor, procurement, and sustainability requirements. Two months later, Micron announced an investment of up to $100 billion over 20 years, beginning with $20 billion by 2030. This project received $6.1 billion in federal subsidies and $5.5 billion in state tax incentives should it meet its targets. Two years later, Syracuse and partners in Rochester and Buffalo won a $40 million Tech Hub award to support related workforce and innovation efforts.

This is one of the most impactful industrial policy investments in the country. The only other investments of comparable size were in very fast-growing regions such as Phoenix (TSMC), Austin, Texas (Samsung), and Columbus, Ohio (Intel). Syracuse thus offers a relatively unique case study of how a region that has not been growing for decades can absorb such an investment in a way that shrinks racial disparities.

How civic and philanthropic leaders are mobilizing federal resources

The relationship between CenterState CEO and CNYCF is being developed in the context of a fast-moving and fluid project that is still in its very early stages (at the time of publication, it has not yet received permits to begin clearing trees for construction). However, these two organizations are beginning to carve out complementary roles, wherein CenterState CEO pulls resources into the region and ensures they align with strategy, while CNYCF pushes those resources deep into communities that might otherwise not benefit, ensuring that small nonprofit organizations have the capacity needed to move at the speed and scale this project requires.

CenterState CEO’s role in attracting the Micron investment and mobilizing complementary resources illustrates the importance of an advocacy and business attraction entity that has the flexible resources required to apply those capabilities in other contexts. CenterState CEO’s role included:

- Federal policy advocacy. CenterState CEO devoted considerable resources to national advocacy for the CHIPS and Science Act. At a 2023 economic forecast event for members, CenterState CEO’s Rob Simpson described spending a summer vacation on the phone with a team from the county, state, and federal government, strategizing and connecting with “chambers of commerce in every part of the country, trying to find swing state senators and congresspeople to vote for this critical piece of legislation that we needed to be able to bring Micron to Central New York.”

- Collaborative state policy development. The state’s Green CHIPS legislation requires that incentivized projects “make commitments to worker and community investment.” CenterState CEO and ESD, however, had to negotiate with Micron to determine the specific terms of a binding Community Investment Framework. The outcome, described further below, is a $500 million Community Investment Fund (CIF) to which Micron is contributing $250 million and ESD another $100 million (to be deployed over 20 years). CenterState CEO also used its expertise to shape other state investments, such as the $200 million ESD is putting into ON-RAMP, a workforce development model designed largely by CenterState CEO (and inspired by Buffalo’s Northland Workforce Training Center).

- Convening to pursue competitive grant funding. The amount of funding associated with the Micron project is colossal, but the vast majority of it goes directly to Micron or is substantially controlled by Micron. There remains a huge need for funding to ensure that the region is capable of absorbing this investment and extending its impact. To this end, CenterState CEO worked with organizational partners in Buffalo and Rochester to pursue and win a $40 million Tech Hubs award that will be invested in workforce development and helping small-to-midsized manufacturers enter the Micron supply chain. CenterState CEO encouraged its peer organization in Rochester to lead the coalition—a recognition that the scale of the Micron project will require contributions from and collaboration among organizations across this “mega-region.”

CNYCF also played an important role attracting capital as a member of the Central New York Community Investment Framework Coalition. This is a group of key funders and partners charged with securing the remaining $150 million of the CIF by building relationships with national philanthropy and coordinating how that funding is received and distributed.

Channeling capital for community impact

Ensuring that this once-in-a-generation flood of investment generates inclusive opportunity rather than magnifying disparities will require thoughtful—but rapid—deployment of capital, specifically from the $500 million CIF and the $65 million that the region received in CHIPS and Science Act workforce development funding. By pairing up, CenterState CEO and CNYCF are attempting to strike a balance between funding organizations that can move quickly and produce dependable results, and funding organizations that best understand the communities that the funding is designed to benefit.

In the case of the CIF, CNYCF co-led the process of establishing the priorities that will influence where and how that funding is deployed. Melanie Littlejohn, president and CEO of CNYCF, was the co-chair of the Community Engagement Committee, which led a yearlong community engagement process that reached 13,000 residents and yielded a Community Priorities Document (CPD) describing a wide range of needs in six areas, from education to small business development to community development and housing. This document is intended to orient Micron and ESD so that their $350 million share of the fund is invested in alignment with these priorities, with the Community Engagement Committee serving as an advisory body. Micron and the state, however, have latitude to fund any proposal that falls in those six broad areas, which cover most plausible economic, workforce, and community development investments. CNYCF will have more direct influence over the $150 million portion of the CIF that will be funded by local and national philanthropies. Littlejohn noted that the organization’s CNY Vitals dashboard is one tool that will allow it to sense community needs at a granular level, as has already been demonstrated with its lead abatement efforts.

For the $65 million in CHIPS and Science Act workforce funding, CNYCF is serving as the official intermediary (designated by the Department of Commerce), with CenterState CEO serving as a sub-intermediary. This arrangement is designed to allow each organization to play to its strengths. Ben Sio, chief of staff at CenterState CEO, noted that while the organization has experience in receiving and dispersing federal funding, CNYCF is better positioned to act as a fiscal intermediary overseeing many small sub-grants, especially those to community-based organizations. Sio said that while CenterState CEO works with a formal network of over 30 training providers on a regular basis, that group is made up of community colleges and large workforce development organizations that primarily do training. To ensure the 8,000 construction and manufacturing jobs at Micron reflect the region’s demographics, training will need to be complemented with intensive efforts led by integrated teams of community organizations who can source and support diverse talent. Positioning CNYCF to engage on that front, he said, “helps us meet a larger goal of driving this work as micro as possible.”

While CNYCF is well positioned to deliver resources to community organizations, ensuring that those organizations are capable of individually and collectively absorbing that funding is another matter. The community organizations that are essential to the region’s strategy are, in many cases, not even incorporated. Littlejohn noted, “We have nonprofits that do tremendous programmatic work, but they still use a paper ledger to do their finances, and the executive director still cleans the bathrooms.” Sio added, “There’s just a massive gap between the capacity of these organizations and the requirements placed on them to get a single dollar of federal or state money.”

This strategy therefore hinges on the region’s ability to quickly and significantly boost the capacity of its nonprofit infrastructure—a role that CNYCF has long played and is embracing in this new era. CNYCF runs what it calls “nonprofit university,” through which it helps small organizations figure out what they’re good at, where and how they should partner, and what is limiting their ability to apply for and manage additional funds. It also does governance training with leaders of community organizations. “But the biggest thing,” according to Littlejohn, “is that we need shared services organizations for nonprofits. We can’t expect them to understand everything about HR, finance, reporting, grant-writing. We don’t expect it in corporate America. Why would I expect it here?” She noted that “these are things that we do in isolation, but if we bring all of these things under one framework, we can build stronger organizations faster than we think.” Littlejohn said that without such investments, any region will rely on the same handful of large nonprofit organizations that have the capacity to manage reports or 50-page funding applications, but reliance on those organizations “may not be able to drive change on a very individual or neighborhood level, and that is the piece that we desperately have to get right.”

Ensuring infrastructure investments keep pace for inclusive growth

It would not appear that funding is in short supply in Syracuse, between Micron’s investment, the billions of dollars in subsidies, the Community Investment Fund, and other grants.

But Micron’s investment is straining systems that were not built to handle a multi-billion-dollar influx. Arguably, the workforce development system has been adequately resourced to respond to Micron’s needs, between the $65 million in CHIPS and Science Act workforce funding, the region’s portion of $200 million in ON-RAMP funding from ESD, and other resources. But nothing equivalent exists to fortify other systems that are equally impacted, such as housing, child care, health care, and infrastructure.

While eventually, Micron’s investment will generate tax revenue that could be invested in these public goods, capturing the benefits of growth and preserving affordability require investment today. And Micron is only half the challenge: In 2025, CenterState CEO reported to members that its pipeline of potential business attraction opportunities has grown more than 20-fold in five years, and doubled since 2024. This pipeline now represents another $10 billion of potential investment. In this context, Littlejohn said the $500 million CIF is “a drop in the bucket. I could spend it before the end of the day and not make a dent. The change we need to make is in the billions.”

Housing is perhaps the most pressing of these challenges. CenterState CEO estimates that the region needs about 2,500 new units annually through 2038, but in the past two years only 350 units were produced annually. CenterState CEO believes that the market could address about half of this need, and another portion would require regulatory interventions. But this would still leave at least 5,000 needed units that would likely not be produced without subsidy. CenterState CEO is in the early stages of designing a fund that would finance the development of mixed-income housing in middle- to high-density settings. This work coincides with CNYCF’s 2023 adoption of impact investing, which would allow it to invest in this housing fund.

To continue to play this intermediary role in workforce development, housing, and other areas, CenterState CEO will need sustained funding for responsive staff and the ability to invest flexibly to fill gaps or fund pilots. This type of funding, however, is in short supply. As CenterState CEO has grown from a $4 million organization to a $25 million organization over the past several years, its flexible resources have grown from just $2 million to $3 million.

Key takeaways for civic and philanthropic leaders

Leaders of local philanthropies can draw several lessons from this case study. First, state policy and regional alignment matter. Much of the Syracuse story is also a New York state story; the state invested in CenterState CEO’s strategic capacity, invested billions in semiconductor assets, and developed incentives aligned with the CHIPS and Science that included requirements related to economic inclusion and community engagement, enabling much of the work described in this case study. (States played substantial roles in most other regional economic turnarounds, including North Carolina in the case of Research Triangle.) Philanthropy should therefore consider state governments—and their decisions around economic development incentives, investments, and policies—as an important lever for regional economic opportunity.

Second, organizations like CenterState CEO can, with flexible resources, become effective conveners and strategists. Regions can pursue business attraction, business leadership, and regional economic development strategy through different organizations, which may be justifiable insofar as business attraction or business leadership organizations lack the incentives or information required to develop inclusive economic development strategies. But there are potentially significant returns to providing a business attraction and/or business leadership organization with the flexible resources to also convene and lead strategy development processes and implement programs. These activities reinforce one another in ways that are possible if done by multiple organizations, but more strongly if done within one organization.

Lastly, community organizations need more capacity and role clarity to operate in emerging, high-growth industries. The Micron project will challenge Central New York’s nonprofit organizations due to its scale, but also its unfamiliarity. In other words, the Micron project is defined by size and speed, but also mystery. For all the work that has gone into laying the foundation for inclusive workforce development, educational institutions and job training nonprofits do not know what specific occupations will be required or what skills and credentials those occupations will demand. To respond quickly as this information becomes available, community-based organizations will need not only individual capacity (e.g., improved accounting practices), but also to be given the cover to play highly specialized roles (e.g., recruitment versus coaching versus training) as part of multi-organizational teams. This requires proactive efforts on the part of funders to allow organizations to define what they are and are not good at.

Case study series

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).