Ten years ago, the humanitarian community adopted major reforms intended to improve response to internally displaced persons (IDPs). Rather than international agencies negotiating on a case-by-case basis to determine who would be responsible for IDPs in a given situation, a cluster system with designated lead agencies was introduced along with efforts to beef up the role of humanitarian coordinators and develop more responsive financial mechanisms. How have these reforms impacted the lives of IDPs? Are IDPs better off than they were a decade ago? This was the central question for a major research project we recently completed.

The bad news is that none of these efforts has prevented new displacement and solutions for most of the world’s IDPs seem further away than ever.

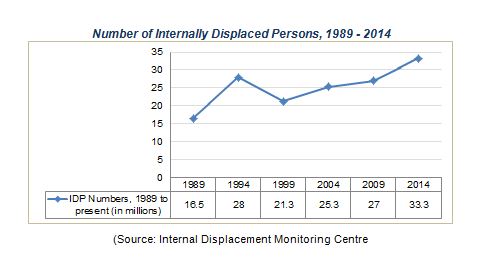

What did we find? The good news is that the 2005 humanitarian reform efforts have generally improved international response to IDPs. Humanitarian agencies are more aware of internal displacement, coordination structures are better, humanitarian leadership is stronger, and the new flexible funding mechanisms are working well. But the bad news is that none of these efforts has prevented new displacement and solutions for most of the world’s IDPs seem further away than ever. As of the end of 2013, there were 33 million IDPs – the highest number recorded since 1982. And it is likely that the number will rise even higher in 2014, given situation reports presently coming out of Syria, Iraq, Central African Republic, South Sudan and a dozen other places. This is almost 10 million more IDPs than there were in 2003. As one respondent in our study remarked, “back in 2004, Darfur was the big new crisis. Now we have 10 crises of the same magnitude.” And the one million people displaced in Darfur in 2004 are still there plus another one million have been internally displaced in Sudan.

While media attention always focuses on the newest large crisis, the dirty little secret is that protracted displacement has become the new normal. People who were displaced 10, 20 or more years ago are still displaced. This protracted displacement is a scandal. Tens of millions of people are living in limbo, eking out an existence with small amounts of humanitarian aid, unable to go home or to start afresh by settling in a new location.

Something is terribly wrong with the international system when humanitarian actors are working in a country for 10, 20 or 40 years with no end in sight.

Humanitarian assistance is supposed to be short-term life-saving assistance which is supplanted in the longer term by development assistance. Something is terribly wrong with the international system when humanitarian actors are working in a country for 10, 20 or 40 years as they are in places like Colombia, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Somalia with no end in sight.

We need bold thinking and new ways of working to end displacement—to enable people to return to their communities or to settle elsewhere in a country. For at least twenty-five years, the gap between relief and development has been lamented and initiatives to address the gap have proliferated. But displacement is still widely seen as a humanitarian – not a development – issue.

But when 15 percent of a country’s population is displaced – as in Colombia – this is a development challenge. When people are displaced for 17 years, this is a development issue. And yet the new post-2015 development goals don’t reference displacement. IDPs need support to recover land or property, to restore livelihoods, to find jobs. These are areas where development actors have expertise.

We need bold new approaches to deal with the scandal of protracted displacement. Maybe it’s time for a new global initiative modeled on World Refugee Year in 1960 when governments, civil society and international agencies worked together to find solutions for the residual caseload of refugees from World War II. Maybe we need new regional initiatives learning the lessons from largely successful efforts to end displacement such as CIREFCA in Central America or the Comprehensive Plan of Action for Indochinese Refugees. Maybe donor governments need to reassess the way they divide their aid budgets between emergency and development aid.

Business as usual isn’t working. Even though humanitarian reform efforts have improved response to IDPs, they haven’t been able to tackle the scandal of protracted displacement. New thinking is needed.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

10 Years After Humanitarian Reform: How Have Internally Displaced Persons Fared?

January 28, 2015