The saying that old habits die hard is especially true in K-12 education. We now have more than a decade of research showing that teachers with masters’ degrees are no more effective at raising student achievement, on average, than those with only a bachelor’s. But many if not most public schools still provide pay increases to teachers who obtain these largely worthless credentials, a practice that is unfair to teachers—who spend their own money and time earning the degrees—and a wasteful use of limited educational dollars.

Teacher evaluation is another case in point. It recently started to look like the beginning of the end for the longstanding practice of cursory evaluations where nearly every teacher receives a satisfactory rating. But well-intended reforms to evaluation have been constrained by having to operate in our highly bureaucratic system of public education. As a result, instead of using information from student test scores and observer ratings as part of a flexible system of evaluation, the new generation of evaluation systems often uses these metrics in a mechanistic, bureaucratic fashion.

A good manager understands that their best employees sometimes have unlucky years, but many new evaluation systems privilege transparency and standardization over flexibility in the name of fairness. Consequently, principals’ hands are tied and news stories highlight well-regarded teachers who received bad ratings. Additionally, the resolve of schools to differentiate among their teachers may be weakening, with “effective” becoming the new “satisfactory.”

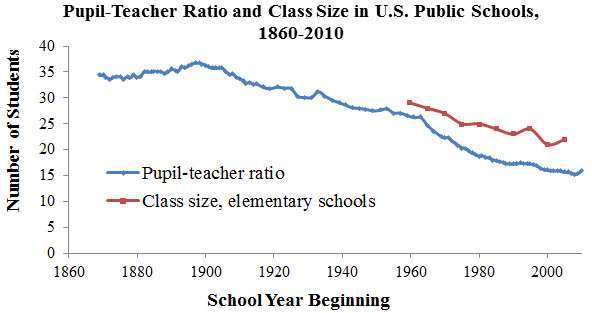

Ignoring evidence and common sense on what works in education has a long history. Pupil-teacher ratios have fallen almost every year for more than a century, with the exception of the Great Depression and the Great Recession, in the face of mixed evidence on the benefits of smaller classes—and especially of untargeted class-size reduction policies.

This doom-and-gloom view is certainly undermined by examples of policy-driven improvements in K-12 education, ranging from accountability to teacher evaluation to no-excuses charter schools. Incremental progress may be disappointing to many who feel the urgency of improving the education received by children from disadvantaged families—by far the best way to increase their chances of climbing out of poverty. But our education system wasn’t built in a day, so it stands to reason that it won’t be reformed in one either.

Commentary

Better Schools Won’t Be Built in a Day, But They Can Be Built

February 4, 2014