Recently, interest in the barriers impeding a child’s success in the classroom reached a national scale with the passage of ESSA including funding support for programs that provide student services, wrap-around services, and services provided by organizations in the community. City Connects, Communities in Schools, and the Children’s Health Fund’s Healthy and Ready to Learn Initiativeare a few examples of programs that support the needs of students comprehensively. With growing public interest in these types of programs, we need to carefully account for costs in addition to effects, especially when comparing against other traditional interventions. Let me explain why.

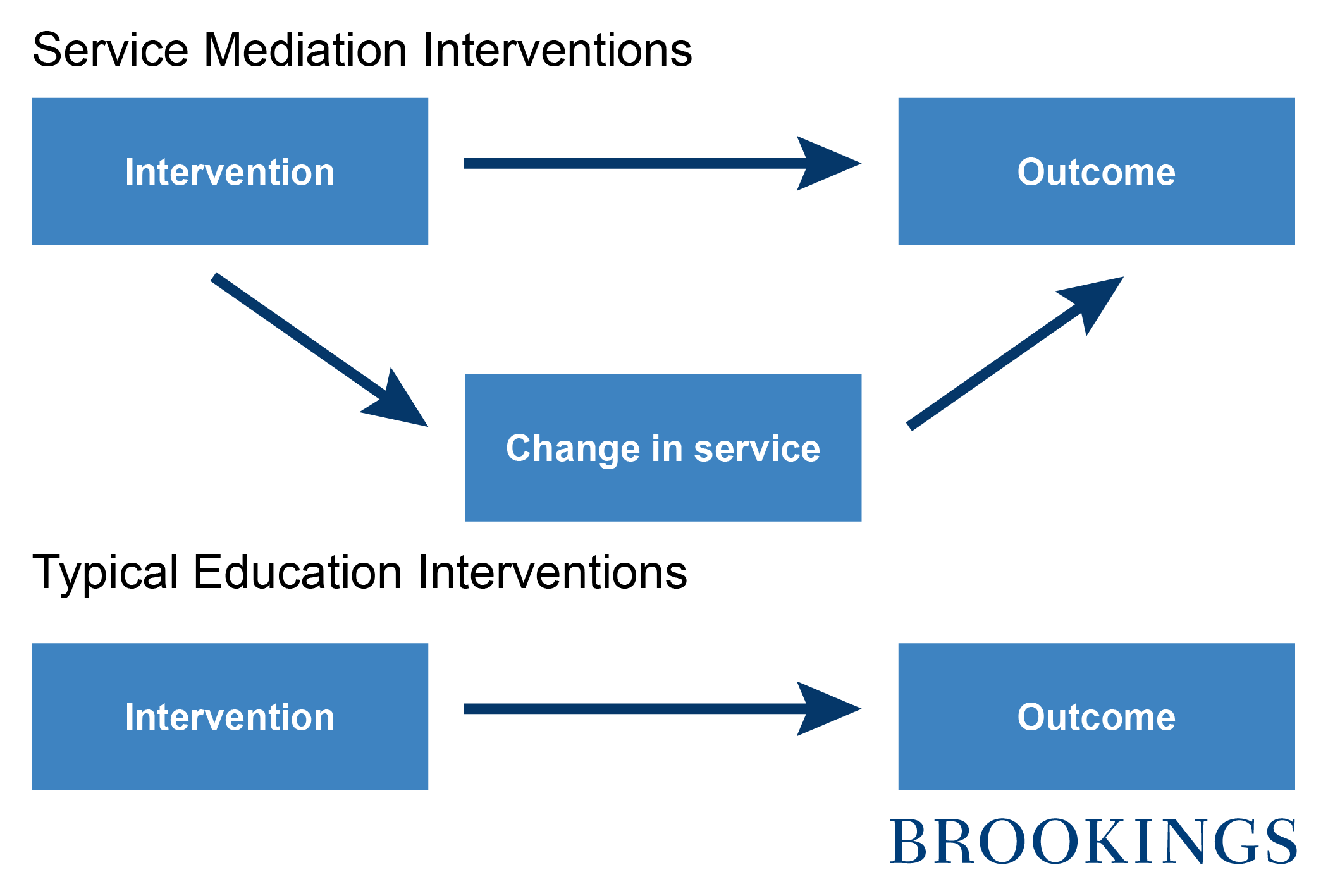

I call these programs Service Mediation Interventions (SMIs). They work by assessing the needs of students and referring those students to community organizations for supplemental support services. A partnership is formed between the school, the program, and community-based service providers that may be governmental, private, or non-profit organizations that offer need-based assistance. These additional services mediate the educational outcomes we care about. And thus they are key to understanding the mechanisms through which impacts are generated. It is not just the intervention causing the effect, it is the intervention and the change in services.

SMIs are distinct from reforms in education that directly impact an academic outcome, for example a volunteer tutoring program that improves early reading.

To accurately estimate costs, we must consider all resources utilized to produce an impact: the resources of the intervention and the resources of the service. Normally, we do not in the case of SMIs.

When conducting a typical economic evaluation, such as cost-effectiveness and benefit-cost analysis, the approach is straight forward: estimate costs of all resources (we call them “ingredients” – like those required to replicate your grandmother’s soufflé) utilized by the treatment and control conditions, subtract control from treatment to estimate the incremental cost that corresponds to the effect, and then pair that cost with the impact. This method works well for typical education interventions, as the ingredients are those that produce the impact.

However, when the intervention induces a change in other services to achieve an effect, it is important that we account for those costs, too. Otherwise, we are not accurately representing the full resource requirement to achieve the impact. And this is where typical cost-benefit approaches for SMIs fall short, and can end up seriously underestimating the costs of these programs.

A benefit-cost analysis of the City Connects program illustrates this issue. The intervention includes program trained staff who are integrated into a school’s administration system to assess the strengths and needs of all students, collaborate with school staff in providing supplemental services and support, and to refer and manage services received from community partner organizations. In addition to the resources provided by the program, the school provides space for the program staff to work, as well as time from teachers and staff to assess students and to communicate about student progress and needs.

While we can assess the cost of the program based only on the ingredients described above in isolation of the services provided by community partners, what is needed is the cost to achieve an impact. Therefore, when an impact is the result of a program like City Connects in conjunction with services provided by organizations such as Strong Women Strong Girls or Cradles to Crayons, the cost to achieve a gain in achievement is the total of all ingredients received above and beyond business as usual. Otherwise, the cost estimate and the interpretation of the impact may be misleading – in the case of City Connects, the cost without consideration of induced services was about one third of the total cost. In other words, for every dollar City Connects spends to help students, other organizations are spending two dollars to provide supplementary services.

Accurate cost-effectiveness figures are important for policymakers and philanthropies to help steer funds to programs with the biggest bang for the buck. Using typical accounting approaches, focused only on costs directly borne by the program, will put SMIs at a serious advantage compared to standard educational interventions. Only by accounting for all costs can these two types of treatment be fairly judged.

Finally, it’s worth noting that wrap-around services are not the only intervention where wrap-around cost estimates are useful. Many education programs involve an intervention and a service, though they may happen at different points in time. For example, a college remediation program may induce additional coursework prior to completion. Another example is a preschool program that causes students to go to better quality schools prior to 3rd grade achievement test score performance.

Evaluations of programs that involve sequential changes for students must include information about the core components of the program as well as implications for service use (now or later) that mediate the measured impact. Without this information, it is difficult to disentangle an intervention from its consequences.

As schools and districts address the comprehensive needs of students, such as hunger, homelessness, clothing, and health, it is our responsibility to provide comprehensive assessments of the resources required. Only then can we know the true cost of achieving impacts, and let the public and policymakers decide whether the benefits are worth the cost.

Commentary

Wrap-around cost estimates for wrap-around services

June 3, 2016