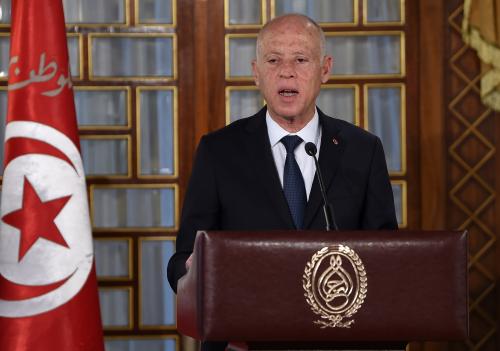

President Kais Saied’s ongoing consolidation of power threatens to end Tunisian democracy, Shadi Hamid and Sharan Grewal write. They argue the U.S. and International Monetary Fund should withhold much-needed loans until Saied agrees to political steps to restore democracy in Tunisia. This article originally appeared in The Washington Post.

Nine long months have passed since the start of the slow-motion coup in Tunisia, a country that, until recently, offered one of the best hopes for democratization in the Middle East. After shuttering the parliament with tanks in July, President Kais Saied has suspended the constitution and dissolved the Supreme Judicial Council. In perhaps the most disturbing move yet, Saied has also now seized control of the independent electoral commission, allowing him to consolidate his rule. How long can a slow-motion power grab persist before it is plainly irreversible?

The world is watching developments in Ukraine with horror, as it should. U.S. President Joe Biden has framed the struggle with Russia as an ideological struggle, as a “battle between democracy and autocracy.” Lately, the Middle East has been an almost entirely neglected front in that struggle. Yet the current crisis in Tunisia offers an opportunity to send a powerful signal in defense of democratic values.

Until now, U.S. officials have been reluctant to put much pressure on Saied. They perceived his July putsch as broadly popular. Many Tunisians were fed up with infighting political parties and a parliament that couldn’t seem to get anything done in the face of a crumbling economy. Saied, a constitutional law professor, pledged to bypass political elites and (somehow) deliver results directly to the people. He alone could fix it.

But he hasn’t. If there were ever a time to rethink and reassess, it would be now — before Saied succeeds in consolidating power and ending Tunisian democracy entirely. As we have seen elsewhere in the Middle East, including most tragically with Egypt’s 2013 coup, once a new regime entrenches itself, the international community’s options and room to maneuver narrow drastically.

The United States has spent too much time hoping that private entreaties for Saied to do the right thing might be persuasive. But urging autocrats to do the right thing for their countries — or for democracy — is nearly always guaranteed to fail. Saied, like other autocrats, does not believe in representative democracy, claiming in 2019 that it “has gone bankrupt and its era is over.” Dialogue and persuasion were never going to be enough to change his mind.

Belatedly, the Biden administration is slowly realizing that rhetorical pressure without any teeth is not working. In late March, the State Department proposed to slash both military and economic assistance to Tunisia roughly in half. Secretary of State Antony Blinken also made clear that the aid would not be restored unless Saied pursues a “transparent, inclusive — to include political parties, labor, and civil society — reform process.”

This is a good start but still limited. A partial suspension of aid dilutes the United States’ leverage by splitting the middle — alienating Saied without fundamentally changing his calculus. Instead, the United States should make clear that if Saied refuses to reverse course, a full suspension will be the result.

Leveraging U.S. aid alone, however, is unlikely to be enough. The United States — in coordination with European partners — must consider something it has rarely done. One might call this the “maximalist” option.

Over the past year, Saied has been negotiating with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) over a multi-billion-dollar bailout that would save Tunisia from a looming default. Such a loan would likely require Tunisia to first develop “a plan for reforms to tackle subsidies, the high public sector wage bill and loss-making state companies,” Reuters reported. The time has come to supplement (if not replace) these conditions with explicitly political ones: that Saied initiate a national dialogue with all major political parties, find consensus on a road map back to democracy, and implement that road map.

To be sure, this is not how the IMF usually operates. Its Articles of Agreement do not specify political conditions; autocrats and democrats alike are eligible for support. However, the United States and European countries, as the IMF’s largest shareholders, can use their voting rights to compel fund officials to push pause on talks.

This might be the best — and last — chance at pressuring Saied to change course. With the economy in free fall, Tunisia needs its Western partners more than ever. As a former senior Tunisian official recently told us, “Saied cannot live without the IMF.” The IMF loan is important to Tunisia not only as a stopgap to fund the state budget, but also as a signal to improve its credit to obtain other loans. (Tunisia was recently downgraded to “CCC,” its lowest-ever credit rating.)

Of course, using U.S. leverage in this way is as risky as it is bold. But, as we have seen over the past year, not using U.S. leverage is also risky. In fact, it risks condemning Tunisians to a full return to the old days of dictatorship. If Americans believe democracy is good, then they should believe that it is good for Tunisians, too. Otherwise Biden’s commendable rhetoric will remain just that — an ideal that we speak about but ignore even in the very cases where it matters most.

Commentary

Tunisia is sliding back into authoritarianism. Here’s what the US should do.

May 12, 2022