Below is a Viewpoint from Chapter 6 of the Foresight Africa 2020 report, which explores six overarching themes that provide opportunities for Africa to overcome its obstacles and spur inclusive growth. Read the full chapter on bolstering Africa’s role in the global economy.

To many nations and international businesses, Africa is increasingly an important investment destination. In August, at the Tokyo International Conference on African Development, Japan’s private sector committed to investing $20 billion over three years in Africa. At the first Russia- Africa Summit in Sochi in last October, the Kremlin announced that $12.5 billion worth of deals were reached, although mostly in the form of memorandums of understanding. Even as Europe wrestles with Brexit, the European Union held the fifth Africa business forum in Morocco last November. And, in an effort to spur investment, the U.S. has sought to revamp its commercial engagement in Africa through the creation of the $60 billion U.S. Development Finance Corporation and a more active commercial diplomatic strategy known as Prosper Africa. The list goes on.

While this trend is welcome, American companies have yet to enter African markets at a significant scale due to the perceived risk in investing there. In fact, only 14 African countries are in the top half of the Transparency International’s Perceptions of Corruption Index, which ranks 180 countries according to the perceived levels of public sector corruption. Conversely, 29 countries from the continent are ranked among the bottom 50 nations. Given the extra-territorial reach of the U.S. Department of Justice in its efforts to enforce the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, American companies are likely to be risk-averse entering many emerging markets, especially in Africa.

Indeed, Paul Boynton, chief executive of Old Mutual Alternative Investments, notes that global investors are holding back because of the perceived risks of investing in Africa, which in reality are much higher than the actual risks. Indeed, the recent governance trend line has been positive, if uneven. The Ibrahim Index of African Governance notes that three out of four African citizens now live in a country where governance has improved over the past 10 years. At the same time, more elections are taking place in Africa than ever before, although fewer than one in six leads to a full transfer of power to the opposition. In fact, virtually every country now holds an election on a regular basis. The African Union, which will suspend a government that comes into power through extra-constitutional means, has committed member governments to “regular, free, fair and transparent elections” through the African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance.

Given Africa’s aspiration for free and fair elections, it is in the interests of the continent’s partners to redouble their funding for improved transparency, fair and free elections, and respect for the rule of law, which inevitably will lead to increased foreign direct investment.

Since the end of the Cold War and the fall of the Berlin Wall, the demand for accountable governance in Africa and regular elections has become one of the region’s defining characteristics. Most recently, for example, in Zimbabwe, an impressive 70 percent of the electorate turned out for the first post-Mugabe elections, though they also tragically resulted in at least six deaths in post-election violence when the military turned on protesters. Given Africa’s aspiration for free and fair elections, it is in the interests of the continent’s partners to redouble their funding for improved transparency, fair and free elections, and respect for the rule of law, which inevitably will lead to increased foreign direct investment.

The U.S. should be a leader in this effort. Africa receives about $16 billion in aid annually from the U.S., including long-term development assistance, humanitarian programs, political aid and military and security assistance. However, when it comes to support for democracy programs—elections, human rights and gender equality organizations, political parties, and legislatures—the amount spent across Africa’s 54 countries in 2017 was a paltry $286 million, only 1.78 percent of total aid, or about $5 million per country. As it concerns investments in anti-corruption programs and institutions in Africa that same year, the U.S. spent only $9 million. This equals just over $165,000 per country, a relatively insignificant amount given the challenges and potential commercial significance of many African markets.

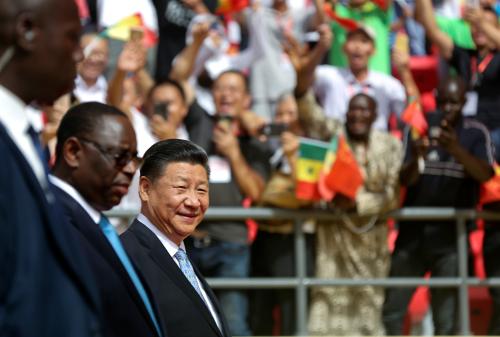

The U.S. would do well to step up investments in Africa’s democratic institutions and processes. A more transparent investment environment in Africa will level the playing field between American companies and many of its competitors, especially those from China. Given the region’s youthful population and the spread of social media in urban areas, the demands for democratic accountability and transparency are likely to grow. So will the demand for jobs, which only the private sector can provide at the required scale. Indeed, employment in Africa continues to be a challenge, as 85.8 percent of employment is in the informal sector, and the region needs to create 12 million jobs annually to keep up with population growth.

Helping to strengthen democratic and transparent processes and institutions in Africa will improve the investment environment. Improved governance will decrease the perception of risk in Africa, and the volume of U.S. investment in the region will likely grow. Both Africa and the U.S. will be significant beneficiaries.

Commentary

Support for governance in Africa will level the playing field for US commercial engagement with the region

January 28, 2020