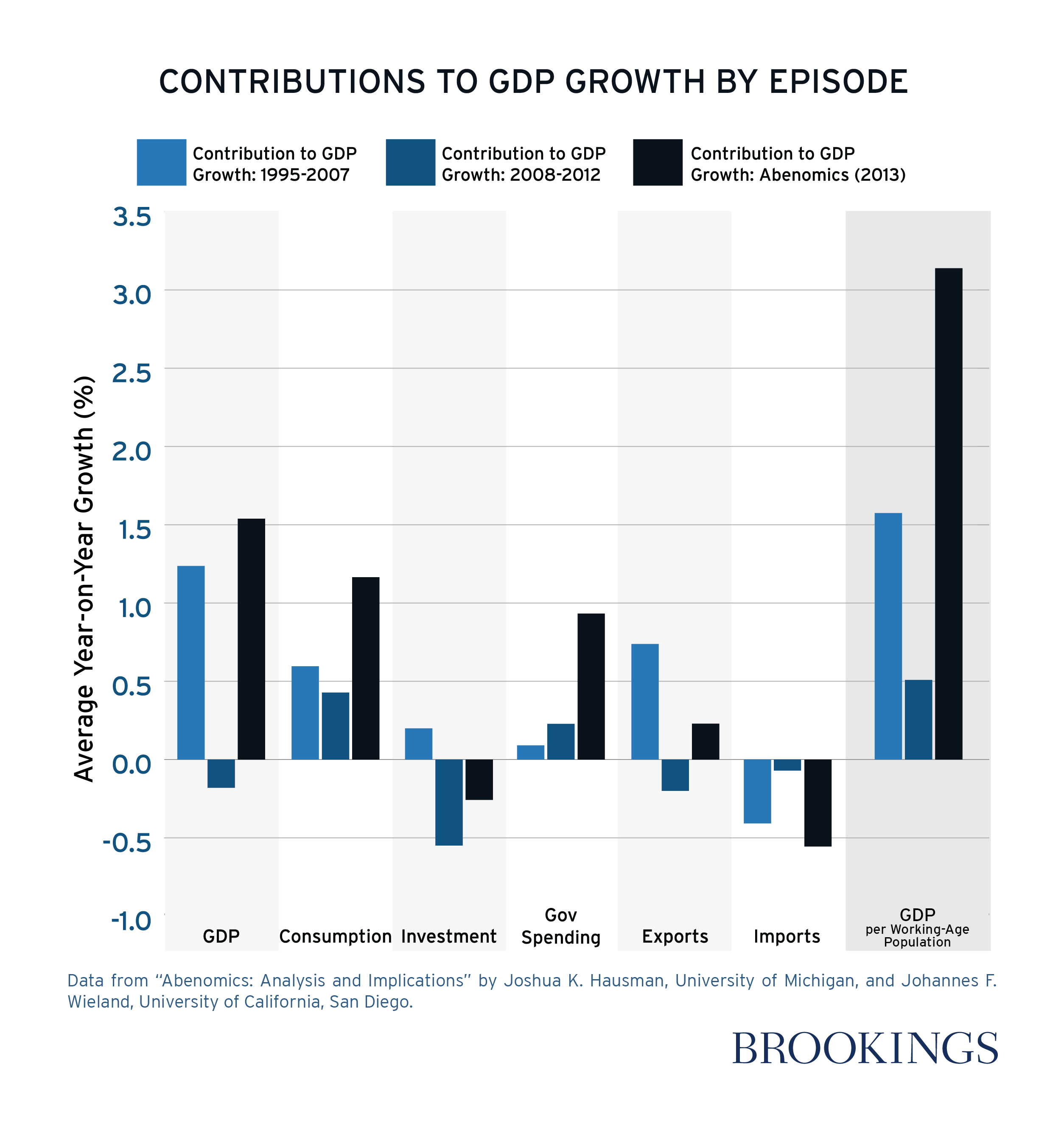

Named after Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, Abenomics includes a monetary regime shift, fiscal stimulus measures, and structural reforms, also known as the “three arrows.” In “Abenomics: Preliminary Analysis and Outlook,” authors Joshua K. Hausman of the University of Michigan and Johannes F. Wieland of the University of California at San Diego examine the impact of those recent policies, with a focus on the most radical arrow, the monetary policy regime shift, because it has the most to teach other countries. It encompasses the Bank of Japan’s new 2 percent inflation target (hoped to be achieved by 2015), which is accompanied by large-scale asset purchases and a doubling of the monetary base (also by 2015). An annual inflation rate of 2 percent would be the highest Japan has had since 1991, just before Japan’s two-decade long stagnation began; from 1993 to 2012 annual Japanese real GDP growth averaged just 0.8 percent, they note.

The research shows that the Bank of Japan is achieving its intermediate objective of higher expected inflation, but that the inflation target itself “remains imperfectly credible,” with long-run inflation expectations below 1.5 percent. Thus the modest estimates of Abenomics’ effects reflect in part that the Bank of Japan has not yet fully convinced the public that inflation will be two percent.

Private sector economic forecasts suggest that Abenomics will cause Japanese GDP to be 3.1 percent higher than it otherwise would be by 2022, which the authors say is a large achievement for any policy, especially one with little or no obvious cost. They find that the welfare benefits of the policy are likely high, but that as of now, it looks unlikely to close the country’s large output gap.

The authors note the contrast between the modest forecast improvement for Japanese output and Japan’s booming stock market, which has been seen as evidence of Abenomics’ success: the Nikkei 225 rose 77 percent and the broader Topix index rose 70 percent from October 2012 to December 2013. Although an increase in stock prices is better than the alternative, at least historically, the stock market has been a poor predictor of dividend growth and is thus also likely to be a poor predictor of GDP growth, they write.

It is possible that Abenomics may work better than current estimates suggest if the Bank of Japan can give more credibility to its inflation target. Politics may partly explain this lack of credibility and could cause the Bank of Japan to have to reverse course, given that rising inflation could lower retiree incomes as well as the take-home pay of current workers. Time will tell if credibility improves and Abenomics outperforms current projections. In particular, Hausman and Wieland suggest several signals that would indicate whether Japan is likely to beat current forecasts:

-

- Inflation expectations—The output effects of Abenomics could as much as double if inflation expectations rose all the way to the Bank of Japan’s 2 percent target, according to their calculations.

-

- Real wages—Thus far, Abenomics has lowered real wages as prices have risen more than nominal wages, but the medium-run success of a higher inflation target may depend on this ending soon. Higher real wages would increase consumer confidence and reduce uncertainty about Japan’s commitment to higher inflation.

-

- Consumption tax—The increase in Japan’s consumption tax from 5 to 8 percent next month is likely to cause uneven growth in the first half of 2014, but if the economy can weather the shock, it would be favorable news for Abenomics, they find.

-

- Structural reform—The largest long-run unknown is what structural reforms will be enacted. If it becomes clearer that bold structural reforms will take place, the authors expect higher growth forecasts to be accompanied by lower inflation expectations.

“The outcome of Abenomics will determine whether Japan experiences another lost decade or resumes healthy growth. Abenomics’ success may also influence policy in Europe and the U.S. As this was going to press, in March 2014, both the Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank were up against the zero lower bound, with inflation near one percent on both sides of the Atlantic. Thus far, neither the Federal Reserve nor the European Central Bank has considered a radical regime shift. If Abenomics succeeds, that may change,” they conclude.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).