Editor’s note: In testimony before the U.S. Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control, Kevin Casas-Zamora outlines opportunities for U.S.-Central America security cooperation. Casas-Zamora pays special attention to Guatemala as a critical transit point for drug trafficking and offers concrete means by which the U.S. can support the battle against insecurity, instability and violence in Central America. Watch the video and download the remarks.

When President Barack Obama signed the annual list of countries with major drug trafficking or drug producing problems in September of 2010, five of six Central American countries made the cut. The list was yet another tangible sign that Central America’s drug-related security plight has reached the level of crisis. Today, the situation in Central America is arguably as grave as in Mexico, which continues to attract the vast majority of news headlines devoted to the issue. In the expansion of the activities of organized crime and the pervasive presence of criminal violence, Central America is facing an unprecedented security and political challenge, one that jeopardizes the region’s undeniable achievements of the past two decades. The end of the civil wars and the democratic transitions in Central America threw a lifeline to a long tormented region, but today that lifeline is at risk of being submerged.

In the next pages I will give a sense of the seriousness of the violence epidemic currently raging in Central America, some of its root causes, and some of most visible consequences. I will argue that the current security crisis in Central America has no quick or easy fixes, and indeed calls for very structural remedies aimed at strengthening feeble state institutions, rebuilding law enforcement systems, and nurturing better opportunities for the region’s youth. Nearly all of this can only be done by the Central Americans themselves. Yet, the United States can and indeed should assist the region in crucial ways. The challenge of organized crime, in particular, cannot and will not be overcome by Central America alone. With more than three million Central Americans living in the United States and a long history of entanglement with the isthmus, Washington has a stake in the future of Central America, whether it realizes it or not.

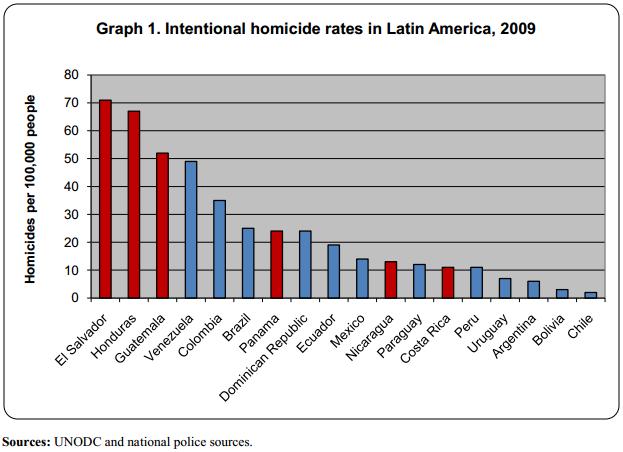

The magnitude of Central America’s violence epidemic. Even by the poor Latin American standards regarding violence, what is happening in Central America is a tragedy (Graph 1). More than 125,000 Central Americans died in the previous decade alone as a result of crime. Almost certainly, this number of deaths is as high as it was at the peak of the region’s civil wars.

The northern half of Central America, comprising Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador, is now the most violent region in the world outside of active war zones. In 2007, Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras had, each of them, more murders than the 27 countries of the European Union combined. Honduras’ current homicide rate (77 per 100,000 people in 2010) is 15 times that of the United States and more than 4 times that of Mexico. Moreover, in the past decade, homicide rates have gone up in every country in the region, in some cases dramatically. Even in the safer southern half of the isthmus, crime figures have taken a turn for the worse, with homicide rates increasing sharply in Costa Rica (63%) and Panama (140%) in the past five years.

Murder rates are merely the most visible human consequence of the problem. According to Latinobarometer 2010, a regional opinion poll, the proportion of households that have been victims of crime in the course of the past year is greater than 25% in every Central American country, except Panama. To this we have to add several other manifestations of violence whose magnitude we can only guess. Approximately 70,000 young men belong to gangs –locally known as maras— in Central America. These gangs have a significant incidence in the region’s violence levels, as well as a growing participation in supporting organized crime.

The roots of violence. The factors behind this deterioration are too complex to be dealt with here at any length. Yet, some of them deserve to be mentioned. To begin with, Central America’s worsening crime rates can hardly be understood but in reference to the narcotics maelstrom engulfing the region. According to United Nations and U.S. government figures, cocaine seizures in Central America have grown six-fold in the past decade. Remarkably, in 2007-2009 countries in the isthmus confiscated more than three times as much cocaine as that confiscated in Mexico – about 100 metric tons per year. Whereas in 2006 close to one fourth of U.S.-bound cocaine shipments crossed to the region, in 2010 the figure was almost certainly higher than two thirds, according to radar tracking from the U.S. government. The intensity of the narcotics trade has direct implications for violence. Guatemala’s government authorities have estimated that 45% of intentional homicides were directly connected to drug trafficking in that country in 2008.

The penetration of organized crime compounds, as much as reflects, two other structural problems: the marginalization of much of the Central American youth and the weakness of the region’s law enforcement institutions. Young people (15-24 years old) in Central America comprise 20% of the total population. They are, however, 45% of the unemployed. One-fourth of the young in Central America are neither at school nor at work, thus becoming a reserve army for criminal organizations and the region’s youth gangs.

Law enforcement problems are, if anything, worse. The region’s police and judicial institutions are underfunded, underequipped and undertrained, as much as they are prone to severe corruption. Unsurprisingly, they command little support from the population. According to the Ibero-American Governance Barometer 2010, another regional survey, only a minority of the population trusts the police or the judiciary in every Central American country. Such mistrust leads to impunity. In Costa Rica, less than one-fourth of offenses are reported to the authorities, an act that is widely considered useless if not counterproductive. The crux of Central America’s crime predicament is easy to identify: its law enforcement institutions are not merely ineffectual to deal with crime; in fact, they compound the problem.

Consequences. Regardless of the causes of this plight, its consequences are very clear and go beyond the obvious human cost. There are economic implications, which become clear when we think that more than half the murder casualties in Central America are young men between 15 and 29 years old, at the peak of their productive and reproductive lives. A recent estimation of the direct and indirect cost of violence in Central America, made by Salvadoran economist Carlos Acevedo, put it at nearly 8% of the region’s GDP.

The political consequences call for special attention. The perception that state authorities are unable to protect the citizen’s most fundamental rights is visibly damaging the support for democratic institutions in Central America and becoming a breeding ground for authoritarian attitudes. A recent study, conducted by political scientist José Miguel Cruz, drew upon data from the Latin America Public Opinion Project at Vanderbilt University to demonstrate that civic support for democracy as a political system is gravely affected by high perceptions of insecurity and by the opinions on the government’s success or failure in the fight against crime. An even more troubling finding is that Central Americans cite crime as the problem that could most easily move them to justify a military coup d’etat. Fifty-three percent of the population of Guatemala, El Salvador, and Honduras would be willing to endure a democratic breakdown, if such a move solved public insecurity problems, a reaction that no other social, political or economic challenge elicits.

The region’s violence epidemic is exerting intense pressure on governments and political actors. Public insecurity currently is perceived as the most urgent problem in every country in the isthmus, except Nicaragua. It is no wonder that the regional debate on security so prominently features –notably during campaign seasons—vociferous pledges to confront insecurity with iron fisted tactics, that is, with methods that make intensive use of state coercion, in ways characterized by a sense of impatience, if not disdain, for basic human rights. The Central American population – as frightened as it is eager for public order– is increasingly heeding as well as rewarding at the polls those loud calls.

This is unfortunate, for the record of iron fist solutions to crime is poor. Both Honduras and El Salvador offer a poignant reminder of this. In Honduras, the enactment since 2002 of successive legislative packages to deal with crime, with clear repressive overtones, has not made any difference at all. At 77 murders per 100,000 people, Honduras’ murder rate in 2010 was far worse than eight years before and the highest in the world. The Salvadoran experience is just as bad. There, the introduction of the Iron Fist and Super Iron Fist acts in 2003 and 2004 was unable to prevent the number of murders from doubling in the seven years between 2003 and 2010.

A second crucial political consequence is the hollowing out of the state and its legal powers. In some places in Central America the firmness of the state’s monopoly over legitimate coercion is open to question. In the isthmus, as well as the rest of Latin America, citizens are defecting from the public instruments to protect personal safety. This defection can take different shapes ranging from the reluctance of the population to report crime, to the proliferation of scantily regulated private security firms, and the acceptance of lynching as a valid method to fight crime. Even in Costa Rica, whose judicial system ranks amongst the best in Latin America, almost 40% of the population looks favorably at the option of lynching offenders, according to UNDP figures.

The situation is considerably worse, however, in places that have been overrun by organized crime, places that can often be found at the very heart of many Latin American capitals. From the favelas in Rio de Janeiro to narcotics-ridden areas in Mexico and Guatemala, drug trafficking organizations have become anything from providers of social welfare to adjudicators of communal disputes. They are the law of the land and recognized as such. At this point, a reference to the situation in Guatemala –the weakest link in the Central American isthmus—becomes unavoidable.

Guatemala’s plight. Guatemala has long been a crucial transit point for north-bound narcotics, mostly cocaine from South America but increasingly methamphetamines from India and Bangladesh. In this role the country has been helped by both geography and institutional make up. The thick unpopulated forests of Petén, in northern Guatemala, which comprise more than half of the country’s 550-mile border with Mexico, offer a haven to drug trafficking activities, often carried out under the complacent gaze, when not the active participation, of public security bodies with a long history of corruption and impunity. Indeed, the Guatemalan state is a feeble entity by almost any indicator, including a tax burden that counts among the world’s lowest. According to recent estimates, up to 40% of the Guatemalan territory is under effective control of criminal organizations.

It is hard to be upbeat about Guatemala’s prospects. It is increasingly clear that the Mexican government’s efforts against drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) in Mexico have driven the latter to expand their operations south of the border. The extensive presence of the Sinaloa and Zetas cartels in Guatemala as well as the vicious turf battles between them, are well documented. Since 2008, the Zetas, in particular, have violently disrupted a reasonably stable equilibrium between local crime syndicates, often allied with the Sinaloa DTO.

In December 2010, the government of President Alvaro Colom, alarmed by a flood of reports of Zetas’ operatives seizing control of villages, raping indigenous women and killing people with total impunity, declared a state of siege in Alta Verapaz, a northern department with a long history of violence and scant state presence. While the return of the Guatemalan Army to Alta Verapaz brought a temporary respite to the region, it was received with decidedly mixed feelings by the local population, Alta Verapaz having been the theater of some of the most egregious human right abuses during Guatemala 36-year long civil war. The two month-long army operation yielded significant seizures of weapons and transportation equipment used by DTOs. Yet, it was generally regarded as an exercise in public relations, geared towards showing domestic and international audiences that the Guatemalan state has not given up hope of controlling its territory. Since the end of the state of siege in February 2011, the situation in Alta Verapaz has reverted to the statu quo ante, with drug-related violence levels continuing their rise unabated there and elsewhere. Indeed, on May 14, 2011, 27 people were killed in a farm in Petén, in what clearly appears as a settlement of a dispute between the Zetas and a local rival. The massacre is probably the worst one in Guatemala since the end of the civil war.

Colom’s decision to send the army to Alta Verapaz is a symptom of the chronic weakness of Guatemala’s law enforcement institutions. Since 2008, the country has had five Ministers of the Interior and four Chief Police Officers, including several with alleged connections to drug trafficking organizations. It was precisely the urgency of dealing with this kind of penetration that led to the decision by the U.N. and the Guatemalan Government in 2006 to establish the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG), with the aim of dismantling illegal groups operating within the country’s security institutions. Ominously, in June 2010, Carlos Castresana, the head of CICIG tendered his resignation, citing the government’s reluctance to clamp down on law enforcement corruption and its lack of support for the Commission’s investigations on organized crime. His sense of disappointment is supported by the figures. According to U.S. government estimations, approximately 250 metric tons of cocaine travel through Guatemala every year. Yet, even an improved counter-narcotics performance in 2009 yielded a mere 7.1 metric tons in cocaine confiscations, a fraction of seizures in Costa Rica, Panama or even Nicaragua.

Guatemala is faced with a growing lawlessness syndrome. The weakness of the state, the pervasive violence, the widespread corruption, and the country’s strategic location for drug trafficking are creating a very dangerous cocktail. The United States and the neighboring countries, which are certain to be affected by the anomie that seems to be engulfing Guatemala, would do well to pay attention and commit resources to help Guatemalans prevent the collapse of their own institutions.

What is to be done? For all the tough talk about iron-fisted solutions, a sustainable reduction of crime levels in Central America requires far more than the use of coercion. It demands a comprehensive policy combination that gives priority to reforming corrupt and ineffective law enforcement institutions, introducing modern technology and information systems to sustain policy decisions, strengthening social ties and the organization of communities, and, above all, investing a lot more in education, health, housing and opportunities for the youth. Such is the road traveled by successful crime reduction experiences in Latin American cities like Bogota and Sao Paulo, which have managed to slash violence levels in little more than a decade. With 80 murders per 100,000 people, Bogota was one of the world’s most dangerous cities in 1994; in 2010, with 23, it was among the safest capitals in the Western Hemisphere. Balancing zero tolerance for crime with zero tolerance for social exclusion offers a way forward even in dire circumstances.

None of this will come cheaply. The public policy interventions that are needed to confront Central America’s crime plight are complex and expensive. There are many reasons why the United States could and should assist in this endeavor. Indeed, the United States is doing so through the Central American Regional Security Initiative (CARSI), a well-designed project to help the region fight organized crime. Yet, even the best counternarcotics assistance program is no substitute for the difficult undertakings that may ultimately deliver Central America from the perils of crime. The Central Americans must accept that, just like achieving peace two decades ago, providing opportunities for young people and rebuilding their law enforcement institutions is something that only they can do.

In order for Central American societies to guarantee universal access to social rights and the adequate performance of their law enforcement bodies, they will have to profoundly reform their taxation systems. Taxes must be paid, lest the states’ ability to exercise effective territorial control is weakened further. At 15.8% of GDP, the average tax burden in Central America is below the norm in Latin America (16.9%) and even Sub-Saharan Africa (17.3%). It stands at less than half of the average tax revenue collected by OECD countries (34.8%). No one can legitimately be surprised that the Guatemalan state has tenuous control over its territory, if tax collection in that country was a paltry 10.4% of GDP in 2009.

In order to successfully battle insecurity in Central America, some of the old demons that have doomed the region to underdevelopment must be exorcised. Criminal violence is simply the place in which all the shortcomings of Central America’s development model are rendered evident. Crime is not merely a security issue. Ultimately, it is a development issue.

Dire though it is, the collapse of public security offers a faint possibility that the region’s elites will come to realize that bringing about more inclusive societies and more effective public institutions is not simply in their own interest but indeed essential to their survival. Here the analogy of Colombia comes to mind. Faced with the abyss of a failing state a decade ago, Colombian well-to-do sectors swallowed the bitter pill of a significant tax hike to fund President Alvaro Uribe’s democratic security policy. Today, the benefits of that decision are all too apparent to be missed. Yet, the limits of the analogy are also plain. It is Central America’s misfortune that the countries that face the most serious threats from organized crime—Guatemala and Honduras—are those where economic elites are more reluctant to changing their ways. Such resistance has roots in their perceived success in vanquishing past political challenges, as much as in the increasing intertwining of their business activities with those of organized crime. In the rest of isthmus the political obstacles that beset major social and state reforms are less formidable, but the sense of threat that may spur action is less evident too.

How can the United States help? As elsewhere, the United States has a limited capacity to dictate what the future will bring for Central America. But it could help the region in meaningful ways. When it comes to security, the following priorities merit attention from the United States.

1. Scale up resources allocated to CARSI and focus on urgent institutional tasks. Since the start of the Merida Initiative in 2008, the funds allotted to the seven members of CARSI (the six Central American countries plus Belize) amount to approximately $250 million – less than one fifth of Mexico’s share of U.S. counternarcotics assistance. This is an indefensible disproportion. It is also a lost opportunity, for CARSI reflects the right priorities in Central America. More than two-thirds of the appropriated funds for the plan in 2010 go to community-based violence prevention programs and to improving the capacities of police and judicial institutions. Less than 10% of CARSI may be regarded as military assistance. This is the right approach in Central America. It would be desirable to avoid spreading CARSI’s funds thin in myriad projects. CARSI can only hope to bring about visible changes if it focuses on a few urgent institutional programs that may exert a catalytic effect on the transformation of the image and efficacy of law enforcement bodies in the region. Particularly urgent tasks on which CARSI could have an impact include:

a. Improving internal control and anti-corruption units within law enforcement bodies;

b. Adopting modern information technologies (from regular victimization surveys to CompStat-like crime data gathering systems) as part of the policy making process;

c. Creating vetted units to handle complex multi-national investigations;

d. Improving investigation and prosecutorial capacities with regards to complex financial crimes.

Crucially, any decision to scale up U.S. law enforcement cooperation with Central America ought to be made conditional on Central American governments raising a matching sum from domestic sources. This exercise in co-responsibility should indeed become a general principle informing U.S.-Central America relations.

2. Support Guatemala’s CICIG. The U.S. government played no small role in the creation of CICIG in 2006. The Commission has proved a valuable resource to carry out complex investigations that, almost certainly, were beyond the capabilities of Guatemala’s law enforcement bodies. After 4 years, the Commission can point to real successes in solving high-profile criminal cases, much as its efforts have on occasion been undermined by rulings by the local judiciary. Ostensible limitations notwithstanding, CICIG remains a carefully vetted unit in a country in which the penetration of law enforcement institutions by crime syndicates is truly rampant. Although the Commission’s mandate was recently extended until 2013, its funding (about $20 million per year) is due to expire in September 2011. Its demise would be a body blow to a country with very few remaining hopes of reducing impunity and upholding the rule of law.

3. Partner with Mexico and Colombia. The riddle of organized crime in Central America can hardly be solved without the active participation of the two major countries that bookend the isthmus and that, in different ways, contribute decisively to the region’s current plight. As U.S. diplomats, including Ambassador William R. Brownfield, U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, have acknowledged in the recent past, a strategy that integrates U.S. efforts against organized crime in Mexico, Colombia and Central America in a common framework is necessary at this point. U.S. assistance is but one component of this endeavor. The fact is that both Mexico and Colombia have developed significant capacities in this struggle that could help their far weaker Central American neighbors. So far, the Mexican authorities have not been particularly forthcoming in assisting their pars in the isthmus, with the possible exception of those in Guatemala. This stands in marked contrast with the Colombian government, whose involvement in the region –in ways ranging from sharing crucial intelligence to training prosecutors and vetted investigation units—is acknowledged throughout Central America. Any U.S. strategy against organized crime in Central America should stimulate cooperation efforts from these two crucial actors in ways that are complementary to the United States’ own programs. As the isthmus’ tragic experience in the 1970s and 1980s shows very well, it is in no-one’s interest to let Central America fall into a vortex of violence.

4. Rethink counternarcotics policies. Central America’s organized crime challenge demands from the United States more than economic assistance, however. If Washington it doesn’t want lawlessness to become the fate of its southern neighbors it is essential to rethink the failed status quo of the so-called War on Drugs and have a rational discussion about alternative approaches, as advocated by the Latin American Commission on Drugs and Democracy in its 2009 report, chaired by former presidents Fernando Henrique Cardoso of Brazil, Ernesto Zedillo of Mexico, and César Gaviria of Colombia. This is not coda for legalization of drugs, but rather a passionate call to look at the comparative evidence available in a dispassionate way. The terrifying cost that Central America is bearing in terms of drug-related violence, drug-related corruption, and the permanent damage inflicted on the work ethics of an entire generation, can and should be mitigated by decisions made in Washington.

These are merely some of the most urgent security-related steps. Since Central America’s security crisis is directly affected by the economic opportunities enjoyed by its youth, the scope of U.S. cooperation ought to be broadened. The United States, for instance, could do a great deal to ease the difficulties that the region faces in the process of taking advantage of the global economy. One can only imagine what, say, $1 billion dollars –the approximate cost of five days of the war in Afghanistan— could do in terms of helping Central America develop clean sources of energy or helping small and medium enterprises –the largest creators of jobs in the region—to take full advantage of CAFTA-DR. These funds could be disbursed over several years and, once more, made contingent on the Central American governments raising a similar sum from domestic sources. In the light of the U.S. current fiscal predicament, this is unlikely to ever happen, but try we must.

For Washington paying more attention to Central America –if not intense attention, at least steady attentionwould not be a favor or an act of charity. In the case of a region that is showing disturbing signs of political instability, that is a stone’s throw away from the United States and that has already sent three million of its people to the shores of this country it could only be considered enlightened self-interest.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

TestimonyU.S.-Central America Security Cooperation

May 25, 2011