Just when it appeared that young adult members of the millennial generation were about to escape being “stuck in place” due to the Great Recession and its aftermath, new migration data from two Census sources indicate that they are not free yet. At the same time, it appears that seniors, including older baby boomers and retirees, are returning to more normal migration patterns.

The diverging generational migration paths are revealed in the Current Population Survey’s Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) trend data through 2012-2013 and the American Community Survey for the three year, post-recession period, 2010-2012, released this week.

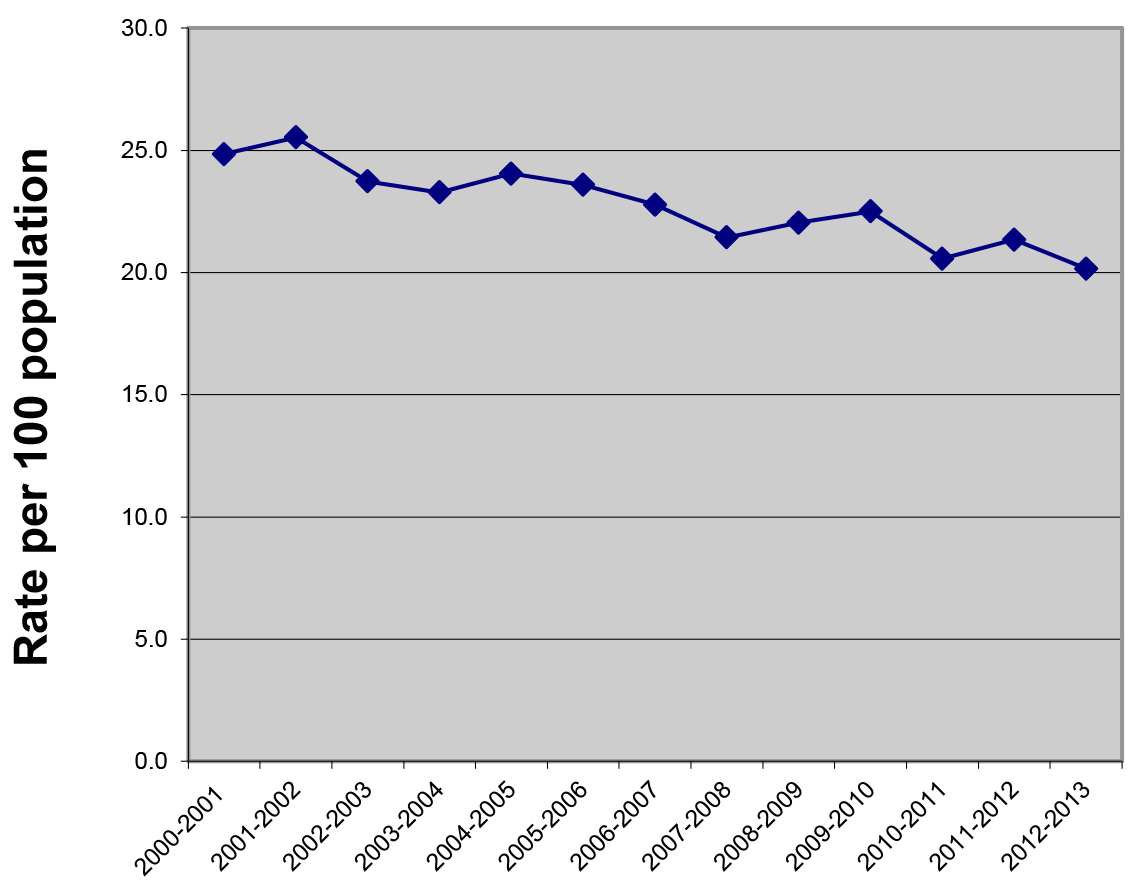

In the past year, young adults aged 25-34 moved at historically low levels, down to 20.2 percent (Figure 1). This is primarily due to a continued dip in local, within county migration, the kind most heavily impacted by housing needs and family formation. Behind the trend is the recession’s resultant credit crunch and continued underemployment effectively reducing homeownership possibilities.

Longer distance moves, between counties and states, did pick up among these young adults in the last two years (at rates in the 6.8 percent to 7 percent range, up from 6.4 percent in 2010-2011). But even these stand at levels well below the 8 percent to 10 percent long distance migration rates observed prior to 2007.

Annual Migration Rates, 2000-2001 to 2012-2013, Young Adults, Ages 25-34

The post-recession moves of seniors aged 55 and above tell a different story. First, they reflect late life job-related moves, tailing off rather than starting careers, along with moves to retirement. Due to more settled life circumstances, older adult migration rates have always been lower than those of young adults. Second, while they did experience a recession-related migration drop-off it was not nearly as severe as for millennials. As the economy picked up and the stock market rebounded, the overall senior migration rate rose from a low in 2011, and their long distance migration rate has steadily increased since 2009.

This post-recession migration revival is most evident in the magnitude and destinations of senior migration. Calculations from one-year moves over the years 2009-2010, 2010-2011, and 2011-12 show a renewed flow of older migrants to both traditional and new “retirement magnet” metropolitan areas. The five greatest gaining areas over the 2009-2012 period—Phoenix, Riverside, Tampa, Atlanta, and Denver—attracted substantially more migrants than during the 2006-2009 recession period. (See PDF Table). Each of the top 12, including the additional Florida areas of Orlando and Jacksonville, received as many or more older migrants than during the recession. Florida showed an average annual gain of 55,000 older people in 2009-2012 compared with just 32,000 in 2006-2009. In short, an emerging senior boom is boosting not only traditional retirement destinations but also emerging ones in the Southeast, Mountain West and Texas.

Young adult millennials, in contrast, did not experience nearly as much of a resurgence. One stark exception to this is Washington D.C. which saw a renewal of young adults in the post recession period—gaining on average 12,500 annually between 2009 and 2012—compared to the loss of young adults during the recession. (See PDF Table). The existence of both government and non-government employment opportunities in a highly educated “millennial friendly” environment make the nation’s capital an attractive destination until migration flows to a broader group of areas emerge. A few other areas, including San Francisco and Minneapolis, have showed a rising post-recession young adult boom as well.

Yet, for the most part, the set of destinations that were able to attract young adults during the recession has not broadened. And except for a few, these millennial magnets attracted fewer young people in the post-recession period. Among the 20 greatest migration gainers from 2009 to 2012, 12 drew fewer young adults in the post-recession period than during the recession. Especially noteworthy is smaller post-recession draw to Texas metropolitan areas like Houston, Dallas, and Austin, and small young adult gains or declines for otherwise rebounding Florida metropolitan areas.

The return to normal for U.S. migration patterns remains a bumpy ride. Perhaps the new senior surge will provide some impetus for broader economic gains in their Sun Belt destinations. What is concerning is that there continues to be a pent-up demand for migration among young adults, the largest potential mover group and the lifeblood of our future housing and labor markets.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edMillennial and Senior Migrants Follow Different Post-Recession Paths

November 15, 2013