Content from the Brookings Doha Center is now archived. In September 2021, after 14 years of impactful partnership, Brookings and the Brookings Doha Center announced that they were ending their affiliation. The Brookings Doha Center is now the Middle East Council on Global Affairs, a separate public policy institution based in Qatar.

With the onset of the Arab uprisings, Gulf monarchies face increased pressure on their traditional ruling balance. Gulf Arab oil monarchies have traditionally been resistant to political reform, and their reaction to the Arab spring has largely followed suit. To focus solely on political liberalization, however, is to ignore ambitious societal and bureaucratic reforms that have been launched in recent years. In many ways, the processes and pressures involved in reforming the state’s “soft institutions” – whether due to pressure from political elites, citizens, or the international community – offer important lessons for broader institutional reform in these cautiously liberalizing monarchies.

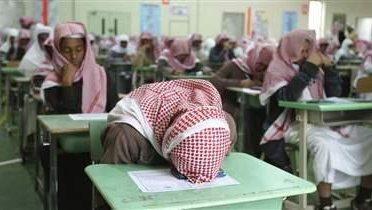

This paper focuses on one of such institution—the educational sector—and analyzes the extent to which reform in that sphere can provide models for wider liberalization. Education reform in the Gulf is a politically charged and socially sensitive endeavour with potential winners and losers among various co-opted groups. Looking at the experiences of three Gulf states—Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates—the study seeks to consider how successful these monarchies have been in transitioning from highly centralized and rigid bureaucracies to more responsive, innovative, and dynamic systems.

While all three countries share certain characteristics, the experiences of education reform in each differ significantly. All three have experimented with varying levels decentralization and privatization. In Saudi Arabia, the institution of higher education is implicated in both the imperatives of liberalization and the regime’s religious legitimacy.

The ruling Al Saud have initiated controversial educational reforms by using peripheral institutions in order to bypass the clerical establishment. Institutions such as academic cities, international partnerships, and quasi-governmental organizations have often provided a backdoor for reform. International accreditation and metrics also provide an external reference, which the regime can use to press for politically sensitive curricular reforms. These strategies have enabled the Saudi regime to accelerate the pace of education reform without directly challenging established institutions and their entrenched interests. However, in the absence of systemic reform that tackles those entrenched interests, the extent to which this model can succeed—and be replicated—remains limited.

In contrast to Saudi Arabia, Qatar has taken dramatic steps to transform its education system. With no cohesive opposition groups, Qatar has been able to quickly implement pilot education reform projects and create the most high-profile branch campus model in the Middle East. Emir Sheikh Hamad bin Khalifa Al-Thani and his wife Sheikha Mozah have lent their support to a range of experimental and ambitious reforms, even outpacing demands from society and many liberal elites. Qatari education reform at both the secondary and tertiary level has been a top-down process, with the royal family as its driving force. As a result of the rapid pace of implementation and limited societal outreach, however, several aspects of the intended reform have become mired in unanticipated bureaucratic and social resistance. The lack of substantive engagement with various stakeholders in the education system prior to initiating an independent schools model led to substantial societal backlash, resulting in a recentralization of administrative control and a backtracking on several of the more controversial elements of the reforms.

In the UAE meanwhile, each of the Emirates has pursued different approaches to the privatization of education, with Dubai embracing an unfettered market approach and Abu Dhabi supporting a statist approach. Due to Dubai’s financial crisis, the more state-centric model is gaining influence as Abu Dhabi asserts a greater role over the federal structure. As in Qatar, Abu Dhabi’s model of education reform has not significantly expanded avenues for societal participation, and the process of generating and implementing education reform remains centralized at the top.

The different models for higher education reform pursued by the three GCC nations studied suggests that demography, ideology, and resources all affect the degree to which a monarchy is able to pursue institutional innovation. A shared tactic, however, is the use of new or peripheral institutions such as Abu Dhabi Education Council, the Qatar Foundation, and Saudi Aramco, to circumvent turgid bureaucracies and rapidly implement high-profile pilot project reforms. Nonetheless, a pilot project does not imply systemic transformation. While education reforms may promote liberalization in other sectors of society—either through creating a better educated, more demanding populace, or through a “beacon effect” —they are unlikely to provide a genuinely replicable model for reform.

Whether the current model of “autocratic modernization” can deliver dynamic and globally competitive public institutions remains to be seen. As shown with the creation of education cities and parallel institutions, it is possible to rapidly implement model reforms through bureaucratic maneuvering. However, these efforts are largely bounded, and their ability to permeate through the rest of the system is limited. Systemic and sustainable reform requires broader societal consultation and modes of participation to limit backlash and increase bureaucratic responsiveness. Without such mechanisms, education reform will likely remain superficial and inadequate to the task.

Leigh Nolan was a Visiting Fellow with the Brookings Doha Center in 2011. Her research focuses on the political dynamics of institutional change in Saudi Arabia, through the lens of higher education reform. Nolan was a Boren graduate fellow in Yemen in 2007 and a Fullbright-Hayes lecturer in Iraqi Kurdistan in the spring of 2009. She received a Ph.D. in International Relations in 2011 from the Fletcher School of Law & Diplomacy at Tufts University.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).