Beginning early in the last century and continuing for decades, Black Americans took part in a “Great Migration” that saw millions move out of the South and into other parts of the country. But over the past 50 years, that historic event has reversed, as many returned to the South in a “New Great Migration.”1

Now, new Census Bureau migration data released over the past year makes plain that this return movement is continuing, although with some dispersion to other parts of the country. This report builds on earlier migration analyses to incorporate new statistics from the Census Bureau’s 5-Year American Community Survey.2

The reversal of the Great Migration began as a trickle in the 1970s, increased in the 1990s, and turned into a virtual evacuation from many northern areas in subsequent decades. The movement is largely driven by younger, college-educated Black Americans, from both northern and western places of origin. They have contributed to the growth of the “New South,” especially in Texas, Georgia, and North Carolina, as well as metropolitan regions such as Atlanta, Dallas, and Houston. And although these areas are simultaneously in the midst of new immigrant growth and white in-migration, the continuing “New Great Migration” has served to give Black Americans a large—and in many cases, dominant—presence in most parts of America’s South.

The historical Black presence in the South and the Great Migration

Prior to the Great Migration, the South had always been the primary regional home for Black Americans. From the beginning of the nation until the start of the 20th century, at least nine in 10 Black Americans resided in the South, predominantly in rural areas. And although the 13th Amendment gave Black residents new freedom to migrate, Black migration from the South was kept at a modest level due to farm tenancy arrangements, poverty, high levels of illiteracy, and the paucity of opportunities in the North.

That changed early in the 20th century with the Great Migration. In the six decades between 1910 and 1970, an estimated 5 million Black southerners left the region. The movement was of such magnitude that, by 1970, the South retained only a little more than half of the nation’s Black population.

Much has been written about the Great Migration in both scholarly and popular writings.3 It took place in two distinct phases: The first, between 1910 and 1930, was triggered by the combination of newly available factory jobs in northern cities (which were further increased by U.S. involvement in World War I) and the slowdown and eventual government restriction of immigration. Together, these events caused desperate employers in cities such as New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Detroit to look to southern Black workers to fill their largely unskilled jobs. And although the pull of northern jobs was a major impetus for migration, there were also strong southern “pushes,” including poor working conditions, Jim Crow segregation laws, political disenfranchisement, and racial violence. Perhaps just as important was the drying up of agricultural employment following farm mechanization and the boll weevil’s damage to cotton crops.

Much has been written about the Great Migration in both scholarly and popular writings.3 It took place in two distinct phases: The first, between 1910 and 1930, was triggered by the combination of newly available factory jobs in northern cities (which were further increased by U.S. involvement in World War I) and the slowdown and eventual government restriction of immigration. Together, these events caused desperate employers in cities such as New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, and Detroit to look to southern Black workers to fill their largely unskilled jobs. And although the pull of northern jobs was a major impetus for migration, there were also strong southern “pushes,” including poor working conditions, Jim Crow segregation laws, political disenfranchisement, and racial violence. Perhaps just as important was the drying up of agricultural employment following farm mechanization and the boll weevil’s damage to cotton crops.

The second phase of the Great Migration took place after a national migration lull during the Great Depression. The huge increase in manufacturing during World War II brought even more employment opportunities to northern cities as well as to western coastal cities such as Los Angeles and San Francisco. The postwar period saw many returning Black military veterans settle in these northern and western destinations. Even as the South became more urbanized and economically vibrant in the 1950s and 1960s, it continued to experience Black out-migration.

Between 1940 and 1970, roughly 80% of all gains in the Black population took place outside of the South. In contrast to their largely rural settlement patterns at the beginning of the Great Migration, in 1970, eight in 10 Black residents lived in metropolitan areas, with one in four living in New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, or Detroit. Similarly, in 1910, the largest Black populations resided in Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama; in 1970, the states with the highest number of Black residents were New York, Illinois, and California.

The ‘New South’ and Black migration back to southern states

By the 1970s, national deindustrialization was underway and conditions in the North changed, adversely affecting Black workers. Deindustrialization led to the demise or relocation of large numbers of blue-collar jobs, many of which Black urban residents had filled. At roughly the same time, the “promise” of northern cities was rapidly diminishing, with many Black residents residing in less advantaged, segregated city neighborhoods. Widespread “white flight” to the suburbs further isolated these neighborhoods from communities where employment opportunities and tax bases were growing.

Black frustration over deteriorating employment opportunities, discrimination, and de facto segregation in northern and western cities led to a series of well-publicized urban race riots in the 1960s. Meanwhile, a favorable business climate coupled with new infrastructure (such as interstate highways) and other improvements (such as the widespread availability of air conditioning) paved the way for industries and employers to head to southern states, marking the emergence of the “New South.”

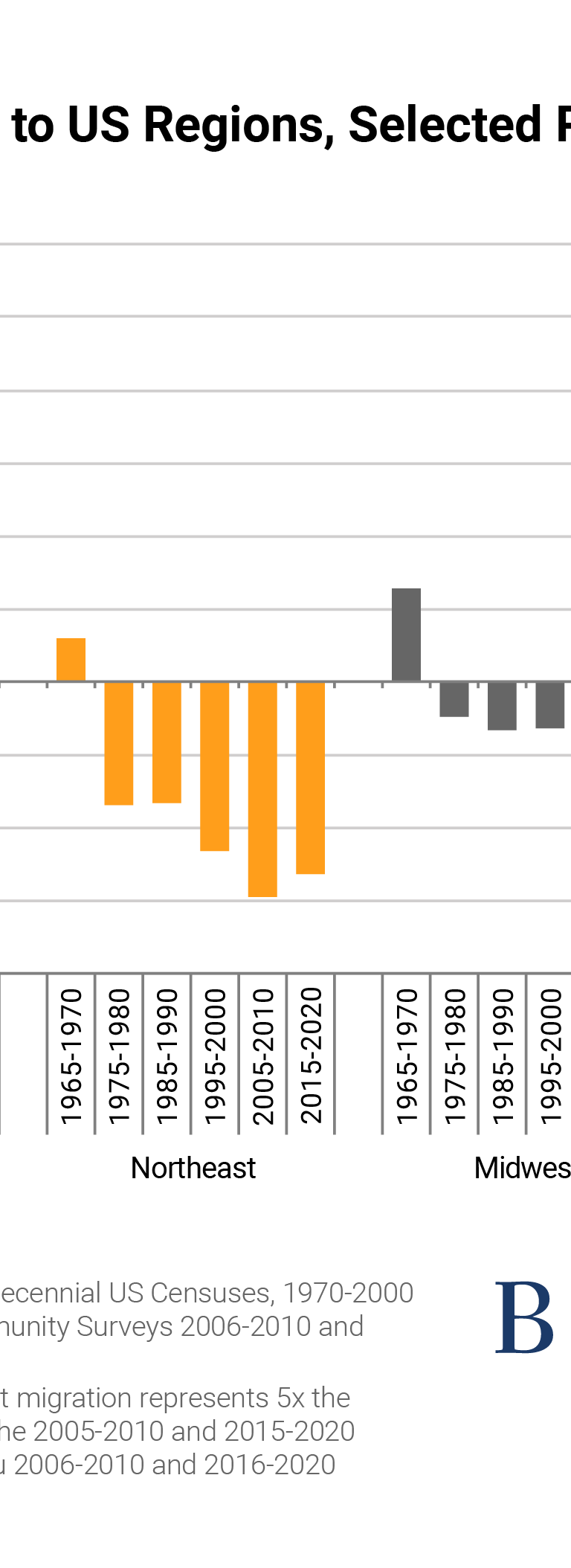

The combined effects of these changing “push” and “pull” factors led to the beginning of the Black migration back to the South in the 1970s. Figure 2 shows the shifts that occurred between five-year migration periods in the late 1960s and late 1970s. From 1965 to 1970, the South was still losing Black migrants to two census-defined “northern regions”—the Northeast and Midwest—and to the West. Yet by 1975 to 1980, the South gained Black migrants overall, due to new migrants from both the Northeast and Midwest.

The combined effects of these changing “push” and “pull” factors led to the beginning of the Black migration back to the South in the 1970s. Figure 2 shows the shifts that occurred between five-year migration periods in the late 1960s and late 1970s. From 1965 to 1970, the South was still losing Black migrants to two census-defined “northern regions”—the Northeast and Midwest—and to the West. Yet by 1975 to 1980, the South gained Black migrants overall, due to new migrants from both the Northeast and Midwest.

A reversal among states for Black migration

At the state level, the New Great Migration was even more dramatic. In the late 1960s, the 14 states experiencing the greatest Black exodus were all located in the South, led by the Deep South states of Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana. At the same time, nine of the 10 states that gained the highest numbers of Black migrants were located outside the South, led by California and Michigan (see downloadable Table A).

By the late 1970s, however, six of the 10 states with highest Black out-migration were outside of the South—led by New York, Illinois, and Pennsylvania. And although California still led all states in Black in-migration, the next six highest were Maryland, Texas, Georgia, Virginia, Florida, and North Carolina. The new Black migration gains were clearly favoring states in the New South: southern coastal states and Texas, where economies and employment opportunities were on the rise.

This was only the first glimpse of a new wave of Black migration back to the South, involving both returning migrants as well as new migrants who were born in other regions. As Figure 2 indicates, southern Black migration gains hit record levels in the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s, as did non-southern Black losses. In the 1990s, for the first time, the South gained Black migrants from the West, especially from California. In both the 1990s and early 2000s, the South gained Black migrants from all other regions.

Black migration gains continued to concentrate in the Southeast and Texas through the 2000s. Georgia led all states in migration gains from the late 1980s through 2005-2010, only to be overtaken by Texas since then (see downloadable Table A). North Carolina, Florida, and Maryland were also among the states that gained the highest number of Black migrants for most years, as was Virginia.

Map 1 shows the sharp contrast in Black migration between the end of the Great Migration and the present. Most of the major Great Migration destination states—including Illinois, Michigan, and California—have become the greatest contributors to the later southern migration gains.

A shift toward southern metro area magnets

As with states, the list of metro areas that experienced the largest net losses of Black migrants changed most abruptly between the late 1960s and late 1970s (see downloadable Table B). In the earlier period, the largest net migration losses (with the exception of Pittsburgh) occurred mostly in Deep South metro areas such as Birmingham, Ala., Mobile, Ala., and New Orleans. But in the late 1970s, deindustrialization in the Northeast and Midwest fueled Black migration out of several metro areas that in earlier decades were their major destinations. New York and Chicago led this list, beginning a pattern of losses that continues to today.

The 1995-2000 period solidified southern metro areas’ dominance as magnets, while at the same time northern and western metro areas such as Los Angeles and San Francisco took the lead in net Black out-migration. Atlanta began its long reign as the top Black migration magnet, outpacing other southern metro areas such as Dallas, Charlotte, N.C., and Orlando, Fla., along with Raleigh, N.C., Columbia, S.C., and, later, Houston, among others. And in the late 1990s, Las Vegas, catching some “spillover” from California, began to show a pattern of Black migrant gains that would later proliferate in western states.

The 1995-2000 period solidified southern metro areas’ dominance as magnets, while at the same time northern and western metro areas such as Los Angeles and San Francisco took the lead in net Black out-migration. Atlanta began its long reign as the top Black migration magnet, outpacing other southern metro areas such as Dallas, Charlotte, N.C., and Orlando, Fla., along with Raleigh, N.C., Columbia, S.C., and, later, Houston, among others. And in the late 1990s, Las Vegas, catching some “spillover” from California, began to show a pattern of Black migrant gains that would later proliferate in western states.

Jobs in prosperous parts of the South are not the only reason that Black Americans have been moving there. Social ties and large Black populations are strong draws as well. The cultural and familial bonds associated with residence within the Black community were evident in the past; although the Black Americans who took part in the Great Migration were less likely to return to the South than white southern out-migrants were during in the same period, they kept in contact with family and maintained kinship networks that promoted further migration. Black Americans’ ties to the region, whether personal or cultural, have also been evident in the southern return, especially among northern city residents who did not fare well during the deindustrialization period and found a familiar and welcoming environment among family and friends in the South. But there are ties to the region for a broad spectrum of Black residents, including retirees with family histories in the South and young professionals who want to join areas with growing middle-class Black populations.

Continued Black southern dominance along with dispersion to other regions

While Black migration continues to concentrate in the nation’s South, it has recently been accompanied by a more localized dispersion into states and metro areas that lie near those sustaining greatest out-migration. Prime examples are Nevada and Arizona, which are among the 10 highest Black in-migration states for each five-year period since 2005; these states draw Black out-migrants from nearby California (see downloadable Table A). Minnesota and Indiana also rose on the Black in-migration list during this period, drawing migrants from Illinois. And in 2015-2020, Pennsylvania and Washington joined the list of the 10 states with the largest numeric Black in-migrants, drawing them from New York and California.

This dispersion has also elevated several non-southern metro areas to the top Black in-migration list, including Phoenix and Las Vegas, and more recently, Riverside, Calif. (in 2010-2015) and Seattle (in 2015-2020)—all reflecting continued Black movement out of coastal California metro areas (see downloadable Table B).

Although region-wide, Black migration to the South declined during the 2015-2020 period, the major southern magnet states of Texas, Georgia, and North Carolina still led all other states in Black in-migration. Similarly, Atlanta was still the greatest net Black migration gainer during this period, followed mostly by other southern metro areas—most notably, Dallas and Houston.

Another recent phenomenon is the rise of a few southern areas among high Black out-migration states (Mississippi and Louisiana) and metro areas (Miami, Washington, D.C., and New Orleans). Nonetheless, the major out-migration states and metro areas are largely located outside the South, led by New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Detroit.

Young and highly educated Black migrants lead the way

While the volume of renewed Black migration to the South is notable, so are the changes that Black migrants are bringing to the region with regard to youth and human capital. While Black migrants to the South exhibit a wide range of family types, incomes, and education levels, professionals and the college-educated in particular are drawn to networking opportunities in southern metro areas with sizeable Black middle-class communities.

It is clear that Black Americans who migrated to the South in recent decades—especially those arriving in economically prosperous areas—have been disproportionately young and well educated. This continues to be the case for the 2015-2020 period (see Figure 3).

Thus, more than a half-century after the civil rights legislation of the 1960s, new generations of Black Americans, particularly those with college educations, are moving away from earlier dominant Black destinations. Although the initial “reverse” migrants may have been fleeing from deteriorating economic and social conditions in the North, recent younger and college-educated migrants are moving to a more prosperous, post-civil-rights-era South that was unknown to their forebears.

Black migration to the South compared to white migration

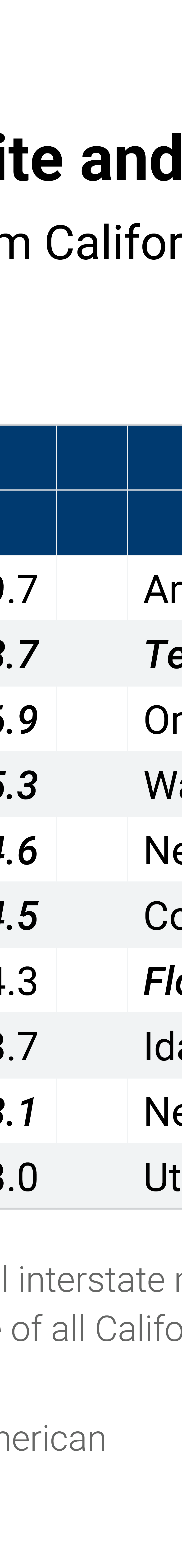

The draw of the South is stronger for Black migrants than it is for white migrants. Figure 4 shows the regional destinations of Black and white interstate migrants originating from each non-southern region from 2015 to 2020. In each originating region, the South is a significant destination for both groups. But in each case, Black migrants are more likely than white migrants to select destinations in the South.

Among migrants from the Northeast, nearly half of Black migrants but less than two-fifths of white migrants chose destinations in the South. In the Midwest, more white migrants chose destinations in other Midwest states (39%) than in the South (35%), in contrast to Black migrants, of whom 43% select a southern state. And in the West, 47% of Black interstate migrants chose a southern destination, compared with just 28% of white migrants.

A comparison of individual state destinations provides a similar contrast (see Table 2). Among all Black interstate migrants in 2015-2020, southern states were the six most popular destinations (Georgia, Texas, Florida, North Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland), and seven of the top 10 states overall were in the South (the previous six plus Tennessee). For white migrants, the southern states of Florida and Texas were the top destinations. However, six of the top 10 destinations were outside the South (California, Arizona, Colorado, New York, Pennsylvania, and Washington).

A comparison of individual state destinations provides a similar contrast (see Table 2). Among all Black interstate migrants in 2015-2020, southern states were the six most popular destinations (Georgia, Texas, Florida, North Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland), and seven of the top 10 states overall were in the South (the previous six plus Tennessee). For white migrants, the southern states of Florida and Texas were the top destinations. However, six of the top 10 destinations were outside the South (California, Arizona, Colorado, New York, Pennsylvania, and Washington).

Among migrants leaving California specifically, seven of the top 10 Black destinations were located in the South (all but Nevada, Arizona, and New York). Yet southern states represented just two of the top 10 white destinations (Texas and Florida), with most California white out-migrants locating elsewhere in the West.

A migration data tool produced by the Census Bureau in collaboration with Harvard University permits analysis of migration flows between 2000 and 2018 for young adults (ages 16 to 26) across broad commuting zones. It finds that among Black movers, Atlanta was the top destination for these young adults from all other commuting zones, and seven of their top 10 destinations were in the South. Among white movers, only two of the top 10 destinations (Washington, D.C. and Dallas) were in the South.

A migration data tool produced by the Census Bureau in collaboration with Harvard University permits analysis of migration flows between 2000 and 2018 for young adults (ages 16 to 26) across broad commuting zones. It finds that among Black movers, Atlanta was the top destination for these young adults from all other commuting zones, and seven of their top 10 destinations were in the South. Among white movers, only two of the top 10 destinations (Washington, D.C. and Dallas) were in the South.

The New Great Migration’s impact on the South

The Black migration reversal has given southern metro areas a demographic boost over the past 50 years. Most symbolic of this change is the five-fold increase of metropolitan Atlanta’s Black population from 1970 to 2020. In 1970, Atlanta had the nation’s 13th-largest Black population, and by 2010, it had modestly outpaced Chicago to rank second in Black population size (after New York). Now, its Black population size is 40% greater than Chicago’s (see Figure 5).

Atlanta has led all other metro areas in Black in-migration for the past four decades. Arguably the capital of the New South, the city is a transportation hub with a diverse array of industries, educational institutions, and corporate headquarters. It has been a migration magnet in general, and especially for Black Americans.

It is certainly true that more recently arrived minorities, particularly Latino or Hispanic populations, are dispersing to states across the South as well. Yet due to the continued in-migration and rising growth of Black residents, it is fair to say that much of the South has returned to its previous status as a region predominantly made up of Black and white populations. No longer do nine in 10 Black Americans live in the South, as was the case over 100 years ago. But that portion has risen from a low of 53% in 1970 to 57% in 2020, and will rise further as current trends continue. (Recent population estimates show that the South accounted for 94% of the nation’s Black population growth during the prime pandemic year of July 2020 to July 2021.) The 2020 census shows that Black Americans are still the largest minority in the South, constituting nearly one-fifth of its population.

So, while there is greater multiracial diversity in large parts of the South, the New Great Migration will continue to ensure that Black Americans remain the largest racial minority in most southern states and in many large metro areas. Figure 6 shows that of the 16 southern states and Washington, D.C., Black residents constitute the largest single racial minority in all but Texas, Florida, and Oklahoma.4 The Black population in each of the remaining states is more than twice as large as the Latino or Hispanic population; and in eight of those states plus Washington, D.C., the Black population is more than three times as large. In metropolitan Atlanta, Black residents constitute one-third of the population, while Latino or Hispanic residents account for just 12%. Black residents also are the predominant minority in Charlotte, N.C., Raleigh, N.C., Nashville, Tenn., Virginia Beach, Va., and Washington, D.C., among other metro areas.

So, while there is greater multiracial diversity in large parts of the South, the New Great Migration will continue to ensure that Black Americans remain the largest racial minority in most southern states and in many large metro areas. Figure 6 shows that of the 16 southern states and Washington, D.C., Black residents constitute the largest single racial minority in all but Texas, Florida, and Oklahoma.4 The Black population in each of the remaining states is more than twice as large as the Latino or Hispanic population; and in eight of those states plus Washington, D.C., the Black population is more than three times as large. In metropolitan Atlanta, Black residents constitute one-third of the population, while Latino or Hispanic residents account for just 12%. Black residents also are the predominant minority in Charlotte, N.C., Raleigh, N.C., Nashville, Tenn., Virginia Beach, Va., and Washington, D.C., among other metro areas.

There is now some Black migration dispersion from traditional settings to fast-growing areas in the West (Phoenix, Las Vegas, and Seattle, for example) or even toward new destination states in the Midwest (Minneapolis) and Northeast (Pennsylvania). But the South—especially its large metro areas—continues to be the major beacon for new generations of Black migrants, as well as those who were born there and choose to stay.

The South that Black Americans are moving to has been changing in fundamental ways. Although Black neighborhood segregation is still substantial, it has declined noticeably in rapidly growing southern metro areas, while Black suburbanization has risen there compared to most other parts of the country. Meanwhile, recent presidential and congressional election results have shown that the Black voting bloc is making the South more politically competitive.

Therefore, whether it is because of family connections, cultural ties, or just the “comfort level” in a region that, for better or worse, is familiar and predictable, the South will continue to stand out from the rest of the country by maintaining a large and increasingly prosperous Black presence, even as it also attracts migrants from other racial minorities.

-

Footnotes

- William H. Frey, “The New Great Migration: Black Americans Return to the South, 1965−2000,” Living Cities Census Series (Brookings, 2004) (https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/20040524_Frey.pdf) and William H. Frey, Chapter 6, “The Great Migration of Blacks, In Reverse” in Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics are Remaking America” (Brookings Institution Press, 2018) (https://www.brookings.edu/book/diversity-explosion-2/ )

- This report extends the publications referenced in Footnote 1. Except when noted, the Black population includes persons identifying as either Latino or Hispanic or Non-Hispanic Black. Net migration data for the periods 1965-1970, 1975-1980, 1985-1990, and 1995-2000 are based on the “residence 5 years ago” questions on the 1970, 1980, 1990, and 2000 decennial censuses. Migration data for periods 2005-2010, 2010-2015, and 2015-2020 are calculated as 5 X the average annual net migration based on the Census Bureau’s 2006-2010, 2011-2015, and 2016-2020 5-Year American Community Surveys.

- Scholarly and popular accounts documenting this movement include: Carole Marks, Farewell—We’re Good and Gone: The Great Black Migration (Indiana University Press, 1989); Stewart E. Tolnay, The African American ‘Great Migration’ and Beyond, Annual Review of Sociology, vol. 29 (2003), pp. 209−32; James N. Gregory, The Southern Diaspora: How the Great Migrations of Black and White Southerners Transformed America (University of North Carolina Press, 2005); Nicholas Lemann, The Promised Land: The Great Migration and How It Changed America (New York: Knopf, 1991); Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (New York: Random House, 2010); and Charles M. Blow The Devil You Know: A Black Power Manifesto (Harper, 2021)

- This discussion, based on Figure 6, pertains to Latino or Hispanic residents, non-Hispanic Black residents, and non-Hispanic members of other racial groups.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).