With Republican Mitt Romney now his party’s presumptive presidential nominee, both his campaign and President Obama’s re-election effort are barnstorming the nation for votes.

For former Massachusetts Gov. Romney, this means recapturing the enthusiasm of the 2010 midterm GOP rout, especially among white Republican leaning voting blocs concerned about taxes and excessive government spending.

For the Democratic president, it means tapping into the groundswell that got him elected in 2008, particularly when it comes to minority voters.

Obama and the Democrats believe demography is on their side. Census 2010 made abundantly clear that racial and ethnic minorities, especially Hispanics, are dominating national growth and will for decades to come. The Democratic agenda— favoring broader federal support for medical care, housing, and education seems designed to curry the favor of these groups, which played a huge role in tipping the balance in his favor in several key swing states.

But while demography is often destiny, it’s not necessarily a slam dunk that minorities can carry the day for Obama this time. The reasons have to do with the complications of translating pure demographics into votes and the outsized role that the nation’s still large white population can exert on national politics.

The 2010 midterm Republican surge is an example. With the economy in freefall and disenchantment with early Obama initiatives rising, even sympathetic white voting blocs—like college graduate women— fled the Democrats in what The National Journal’s Ron Brownstein termed a “white flight.”

Of course the president’s public approval ratings have risen since then, and the economy has picked up some. The country is clearly not at the same place economically as it was in 2008 or 2010.

Recently released Census Bureau Current Population Survey data from January 2012 permit a simulation of this year’s election under different white and minority voting scenarios. They show that Obama’s reelection is even more dependent on minority support than in 2008—and not just in the most racially diverse states. Two factors are key to translating minority population into votes in 2012: eligibility and turnout.

The minority/eligible voter disconnect.

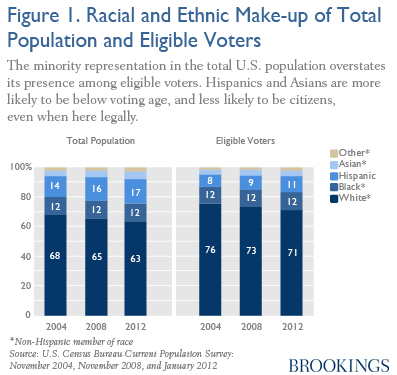

The minority representation in the total population overstates its presence among eligible voters because our fastest growing minorities are either too young to vote or are less likely to be citizens, even when here legally. For every 100 Hispanic residents in the United States, only 44 are eligible voters aged 18 and over and U.S. citizens. In contrast, 78 of every 100 white residents are able to vote. In this respect, Asians are more like Hispanics and blacks are more like whites. So even though minorities are growing faster than whites overall, the latter are more heavily represented among eligible voters (71 percent) than in the total population (63 percent).

This disparity is even larger in many fast growing “new minority” states. In Nevada, whites comprise 51 percent of the population but fully 61 percent of eligible voters. Other states where minority voters are strongly underrepresented include Arizona, California, Texas, and Florida (Table 1).

Further diminishing minority electoral clout is lower voter turnout. In each of the last two elections, the share of eligible minority voters who voted was 15 to 20 percent less than for whites. Turnout rates were smallest for the fast growing Hispanic and Asian populations. As a consequence, the white share of actual voters will be even larger than it is among eligible voters (estimated to be about 75 percent of voters in November).

Why minorities mattered in 2008.

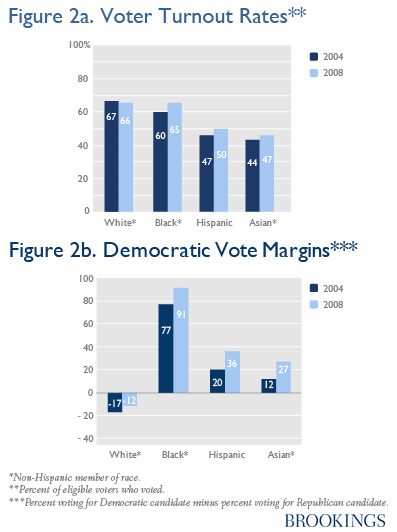

Minorities mattered in 2008 for three reasons: first, their relative sizes compared with whites increased in each state; second, their enthusiasm for the Democratic candidate was greater than in 2004; and third, white support for the Republican candidate (John McCain) waned in comparison to the previous election.

The uptick in minority enthusiasm for the first black presidential candidate resulted in higher turnout rates, and larger Democratic vote margins nationally than in 2004. This was the case in most but not all states, including Nevada and Florida, where Hispanics, blacks, and other minorities turned the tide toward the Democrats.

Often overlooked, but just as important, was weaker white Republican support in terms of both turnout and margin. Although whites dominated the electorate in states like Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Indiana, their tepid support for McCain opened the door for those states’ much smaller minority populations to tip the balance to Obama. In more diverse states like North Carolina and Virginia, minorities would not have made the difference were it not for sharply lower white Republican support than in 2004.

Minorities and the 2012 election.

As we approach November, minorities will account for a slightly larger share of eligible voters than in 2008. At the same time, white support for the Republican candidate may be greater than in 2008. Which dynamic will prevail?

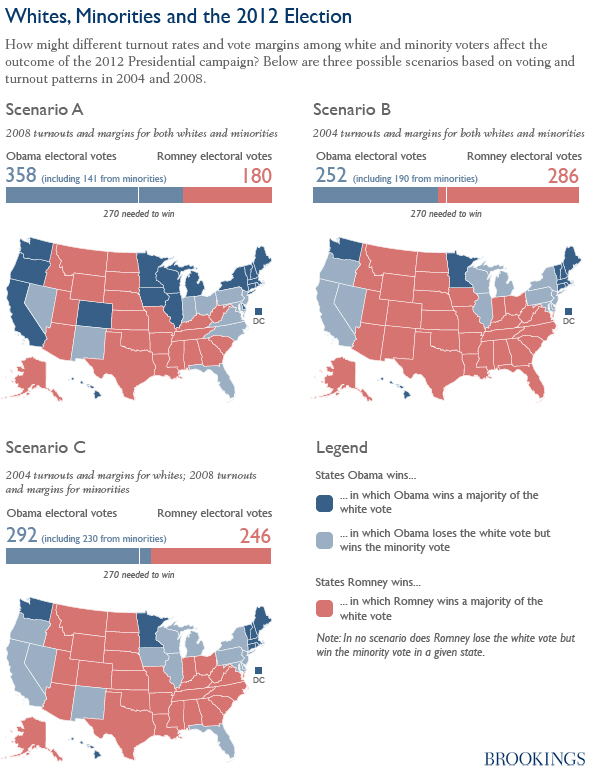

Three simulations—based on January 2012 eligible voter populations in every state (Table 2), but with different assumptions about white and minority turnout and voting—provide clues as to November’s possible results Each simulation assesses how many states and Electoral College votes Obama and Romney would win, and for which states minorities are responsible for the win (states where whites voted for the losing candidate).

Scenario A, the best case for Democrats, assumes that the 2008 turnout and voting patterns again apply to new population. If that occurs, Obama wins with 29 states and 358 electoral votes. These are the same states he took in 2008—changing racial demographics did not put any new states in his column. As with the 2008 win, 10 state victories (representing 39 percent of his electoral votes) can be attributed to minority voters. These states put him over the winning 270 electoral vote threshold.

Scenario B, the best-case for Republicans, applies 2004 turnout and voting patterns to the 2012 population. This time, Romney beats Obama with 286 electoral votes in 30 states. The stronger white support for Republicans here, compared with Scenario A, is evident even in big states taken by Democrats, like California, New York and Illinois where whites voted Republican and minorities were responsible for the wins.

Scenario C signals something closer to what this year’s election promises—strong partisan participation for both whites and minorities. Whites in each state are assumed to mimic their 2004 turnout and voting patterns, reflecting higher levels of enthusiasm for the Republican nominee than in 2008. Minorities are presumed to follow their strong 2008 turnout and voting margins. The results favor an Obama win—but barely.

Obama squeaks by with 292 electoral votes spread among 24 states. Of these votes, 230 are attributable to 14 states where the minorities were responsible for his victory (including eight where whites voted for Obama in 2008). In essence, about four-fifths of Obama’s electoral votes are attributable to states won by minorities. Among the new states where Obama depends on minorities under this scenario are California, New York, Illinois, Michigan and Wisconsin. Among the 14 states, Obama’s victories in Florida, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and Oregon (66 electoral votes total) would be particularly close.

This scenario awards Romney five states that Obama won in 2008: Ohio, North Carolina, Virginia, Indiana and Colorado. The 27 states (and 246 electoral votes) that Romney gains under this scenario are not all decisive wins either. While whites vote Republican in each, overall margins are very close in Ohio and Missouri, large states with substantial minority populations.

Whatever scenario comes to pass, minorities are going to matter in November. The new demography of the electorate guarantees it. Their significance lies not just in racially diverse battleground states on the coasts, Southeast, and Mountain West. If the white Republican base turns out in full force, the votes of African Americans and growing Hispanic populations will be necessary for Democratic wins in a slew of interior states with largely white electorates. The 2012 election will most assuredly be a battle of turnout and its outcome will greatly depend on the enthusiasm of minority voting blocs.

Editor’s Note: This piece has a follow-up paper written after the 2012 election.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edWhy Minorities Will Decide the 2012 U.S. Election

May 1, 2012