It’s impossible to know how bad the Middle East is going to get this year. There is mounting evidence to suggest that it could get really bad. Of course, worst cases tend to be mercifully rare, and so we can reasonably hope that the region won’t get as bad as it seems like it might. Then again, this is the Middle East we’re talking about, and in the Middle East, the worst case is unfortunately often the most likely case.

One aspect of how bad the Middle East could get this year lies in the confluence of events in Syria and Iraq.

A few weeks ago, a well-connected Saudi told me, “We see the Syrian civil war and the [coming] Iraqi civil war as the same, and we will treat them as the same.” He explained his point this way: from Riyadh’s perspective, there are Iranian-backed Shia governments in both Syria and Iraq that are oppressing their Sunni populations—Sunni populations that Saudi Arabia and other Sunni Arab states feel increasingly determined to support. He even reminded me that the Sunni tribes of eastern Syria were the same as those of western Iraq. Tribes like the Jubbur and Shammar span the border. So providing money and weapons to the Sunni tribes of eastern Syria is effectively the same as providing money and weapons to the tribes of western Iraq.

Who knows if my interlocutor spoke for the Saudi government. His words seem consistent with Riyadh’s world view and with the approach the Saudis were threatening to take back in 2006, during the darkest days of Iraq’s civil war. But as my friend Greg Gause likes to say about understanding the Saudis, the problem is that “those who know don’t talk, and those who talk don’t know.” Still, even if he was wrong, he could still be right.

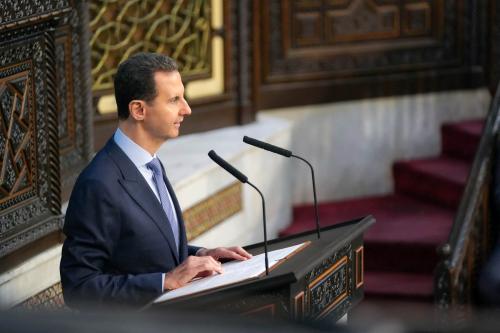

By any measure, Syria has already crossed the threshold of civil war, and the situation is likely to get worse before it gets better (if it gets better). The Assad regime, and the Alawi Shia community that stands behind it, have shown absolutely no willingness to step down or compromise and appear utterly determined to use as much violence as necessary to stay in power. Indeed, most reports indicate that the Alawis fear that if the regime falls, they will be slaughtered by the Sunni majority they have oppressed for more than 50 years. Consequently, they plan to fight as hard as they can and kill as many as they must to retain power. For its part, the opposition Sunni majority has refused to be cowed by the regime’s violence and is gaining in its own ability to wage war against the regime.

This is not a recipe for peaceful revolution such as we saw in Tunisia and (mostly) Egypt. It is a recipe for deepening conflict, like Libya or Yemen or worse. Unless the regime finds a way to greatly ratchet up the violence and so crush the opposition quickly—or an external great power decides to intervene in force and so snuff out the conflict altogether—the most likely scenario will be a bloody, protracted war.

We should expect that spillover from Syria—which has already affected Turkey, Lebanon and to a lesser extent Israel—will worsen and will also affect Iraq and Jordan.

One of the biggest problems with such intercommunal civil wars is that they don’t stay contained within the borders of the state. Spillover from civil wars is an inevitability, although it can range from quite mild to very severe. Unfortunately, Syria has all the hallmarks of being on the worse end of the spectrum: porous borders, ethno-sectarian communities that span them, irredentist claims, and longstanding grievances with neighbors. My Saudi friend’s point about Iraq gets at exactly this problem, and we should expect that spillover from Syria (which has already affected Turkey, Lebanon, and, to a lesser extent, Israel), will worsen and will also affect Iraq and Jordan.

Spillover from civil wars typically manifests itself in six pernicious ways: terrorism, refugees, economic dislocation, radicalization of the neighboring populations, secessionism, and intervention by neighboring states. In 2006, Iraq was creating all six of these problems for the other states of the Persian Gulf—conjuring widespread panic that the Middle East was going to hell in the proverbial hand basket—only to see those fears abate when the United States changed its strategy and, with the “surge,” successfully suppressed the violence and the civil war. At their worst, civil wars in one state can cause civil wars in another: civil war in Lebanon led to civil war in Syria in 1976-82, the Rwandan civil war sparked the Congolese civil war of the 1990s, just as civil war in Afghanistan is pushing Pakistan to the brink of civil war today (and might push it over in future). Civil war can also lead to regional war as neighboring states intervene in the country in conflict to protect their own interests and prevent their regional adversaries from gaining an advantage: the Congolese civil war invited intervention by seven of its neighbors, Lebanon led to an Israeli-Syrian overt fight followed by a proxy war, Afghanistan led to a covert war between Russia and Pakistan (backed by the United States) and there are numerous other cases along these lines.

Not that Iraq needs any help finding its way back to civil war. It is doing just fine marching smartly down that path all by itself. Despite the progress made in 2008-09, Iraq still has deep structural flaws in its political system that were not fully addressed during the period after the surge when the country made the greatest political progress. The withdrawal of American troops before those flaws were fully addressed has not only revealed the depth of the problems but set back the progress considerably. Baghdad is deeply enmeshed in a crisis, and even if the current situation can somehow be defused, unless all sides show a willingness to compromise and address these deeper issues in a way that they haven’t since the withdrawal of U.S. forces began, crisis will likely follow crisis and the country will end either in civil war, an unstable dictatorship (that will lead to civil war of one kind or another), or a Somalia-like failed state with its own lawlessness and violence.

The prospects for Iraq to muddle its way out of the civil-war trap alone were always daunting, but they take on new seriousness when one considers the likely impact of spillover from a Syrian civil war. Almost invariably in civil wars, armed militias look for sanctuary in neighboring states—particularly those where they have ethnic, religious, tribal, or even political brethren on the other side of the border. The worse the violence gets in Syria, the more that Sunni tribes in Syria fighting against the Alawi Shia regime will look for sanctuary and succor from their brothers in Iraq. Their brothers in Iraq are already contemplating a new conflict against the Shia-dominated regime in Baghdad, and may well look for assistance from their Syrian brothers. Meanwhile, the more that the Saudis, Jordanians, Emiratis, Kuwaitis, and Turks see both of the regimes in Damascus and Baghdad as Iranian puppets (which they all do already to a greater or lesser degree) the more that they will arm the Sunnis in both countries, isolate the regimes of both countries, and possibly even try to push back on the Iranians directly.

The dire warnings of a great Sunni-Shia war that seemed like ridiculous fear-mongering just a few years ago could well become a tragic reality if the Sunni Arab states become determined to prevent Iran from retaining its ally in Damascus and creating a new one in Baghdad. At the very least, their competition for Syria and Iraq, which is already beginning to heat up, is likely to make the situation in both countries worse. At its worst, such efforts to wage a proxy conflict across both countries might apply enough heat to virtually fuse the two civil wars, which would add tremendous fuel to both fires and make it much harder to extinguish either.

How bad could it get in the Middle East? Potentially pretty bad. We have tended to fret about developments within each country, and have at times reassured ourselves that the situation won’t get too bad because of restraints inherent in each country’s situation. But by mentally compartmentalizing them, we may be underplaying the real potential for problems. We must be awake to the possibility, even likelihood, that the problems of Iraq, Syria, the Gulf, Jordan, Lebanon, Israel-Palestine, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, etc. could interact to produce a whole that is even worse than the sum of its parts. And like civilization itself, it might all start on the banks of the Euphrates.

Commentary

Op-edThe Revolt in Syria Could Easily Spread to Other Middle East Countries

January 31, 2012