This piece originally appeared in Real Clear Policy.

One of President-elect Trump’s top priorities, in service of his overall goal of jump-starting economic growth, is to limit, unwind, repeal, or delay a host of regulations, executive orders, agency guidance, and presidential memoranda promulgated by the Obama administration. Trump’s ability to effect these relatively quick reversals is a natural consequence of the Obama administration’s “We Can’t Wait” approach, in which policy is made with a “pen and phone” rather than “waiting for legislation.” Laws that live by pen and phone can die by pen and phone.

The Trump campaign’s website highlights the Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Power Plan and Waters of the United States rule as well as the Department of the Interior’s moratorium on coal mining permits as part of a “targeted review for regulations that inhibit hiring.” Other rules in the new administration’s crosshairs include the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule and its overtime rule; somewhat farther down the list may be the Dodd–Frank Act’s Volcker Rule and the Federal Communication Commission’s net neutrality rules.

Some of these rules may be easier to reverse than others, depending on what stage of the regulatory process they are in after Inauguration Day. Proposed, but as-yet un-finalized rules are most amenable to change or elimination; final rules recently enacted can be eliminated in collaboration with Congress, as stipulated in the Congressional Review Act (CRA). We will have to see whether the lawyers of the new Trump administration pioneer new ways of dislodging finalized rules — especially those, such as the Clean Power Plan, currently facing significant legal challenges.

Even when agencies seem to be locked in to a particular course of action, there are any number of ways to slow the flow of regulations. Final rules not subject to the CRA could be delayed or deprioritized within individual agencies, or, perhaps, eventually repealed or defunded by Congress. The Trump administration could also reopen the cost-benefit analyses underlying important rules, many of which are controversial. One early indication of this strategy is that the Trump transition team for the Department of Energy has been questioning the use of the “social cost of carbon.” Determination of this cost — including whether to measure only the domestic rather than the global benefits — substantially influences the estimated net benefits calculated in the regulatory impact assessments of carbon-reducing regulations.

Of course, it is another question which, if any, of these rules should be reversed. Here a conceptual approach to regulation is needed, one that identifies market failures, analyzes the benefits and costs of different interventions, and assesses the risks of any unintended consequences. Yet another question is whether and to what extent reversing regulations improves the average American’s well-being, rather than simply boosting economic growth. The latter is important, of course, but the former can include non-market benefits not captured by standard measures of national economic output.

The motivation for regulatory unwinding is the belief that the steady increase in the number of regulations has led to more regulatory complexity and intrusiveness, increasing the cost of compliance and creating drag on the economy. There is no reliable and precise measure of the regulatory burden. It is challenging enough to measure counterfactual benefits and costs for individual regulations meant to address market failures, let alone an aggregate measure for the totality of regulations. One report puts the compliance and economic costs at nearly $1.9 trillion annually. Whatever the reliability of such aggregate measures, there is ample evidence that regulation has expanded and that this expansion has limited economic growth.

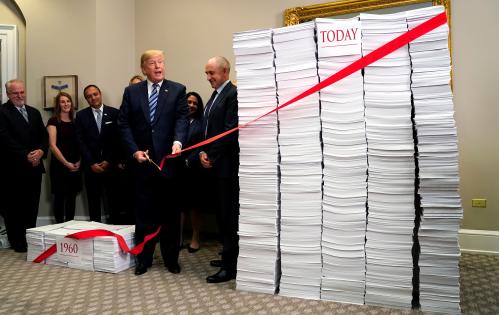

In 2015, the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), the compilation of all federal regulations, was approximately 175,000 pages long — a nearly eight-foldincrease in the past 55 years. According to the World Bank’s recent Doing Business report, the United States ranks 51st out of 190 countries for ease of starting new businesses, a steep fall from 2010, when the U.S. ranked eighth. While state and local regulations are partly to blame for this, federal regulations are undoubtedly significant.

A number of studies suggest an increase in federal regulations has had a deleterious effect on economic activity. One study, which measures the increase in the number of pages of the CFR over time, concludes that “regulation has caused substantial reductions in the growth rates of both output and total factor productivity.” Another more recent study focuses on 22 industries from 1977–2012. It finds that “regulation — by distorting the investment choices that lead to innovation — has created a considerable drag on the economy, amounting to an average reduction in the annual growth rate of the U.S. GDP of 0.8 percent.” No surprise that businesses appear to be responding enthusiastically to President-elect Trump’s regulatory agenda, fueling the boost to markets and to confidence.

Another priority for Republicans will be to change the regulatory process itself. Process-oriented regulatory reform has been percolating in the House for several years now, and it seems to have momentum going into 2017. Some proposals for how to do this were already outlined in Speaker Ryan’s “A Better Way” plan. These include requiring agencies to analyze several regulatory alternatives and choose the most cost-effective among them; to do advance planning for an effectiveness review after several years of policy implementation; and to improve data transparency practices to facilitate crowdsourced oversight. Another goal is to make administrative rulemakings easier to contest in court when they rely on flawed cost-benefit analyses.

Finally, congressional Republicans also plan to push the Regulations from the Executive in Need of Scrutiny Act (REINS). This would make all major rulemakings go through Congress before taking effect and instruct courts to end Chevron deference — the practice of giving federal agencies’ power to interpret statutes when there is ambiguity.

How much this dovetails with President-elect Trump’s agenda remains to be seen. In his plans for the first 100 days, Trump promised to make agencies get rid of two rules for every new one they put in place. As Susan E. Dudley, former Administrator of the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, point out, similar plans have been tried in other countries with debatable success. In any case, Trump’s proposal is somewhat different in approach from Ryan’s, and it is too early to say what would emerge from a collaborative effort between the new administration and congressional Republicans.

Large-scale regulatory reform may help legitimize America’s vast regulatory state by ensuring that rule-making processes are fair, conducive to efficiency, and informed by the best available evidence. Addressing these fundamental concerns may help citizens feel less disempowered and ignored by an insular government.

But there are perils, too. Well-meaning constraints on bureaucracy have a way of accumulating and paralyzing government, leading to wheel-spinning and endless litigation rather than effective government. There is no reason to think current reform efforts will necessarily mitigate this problem. If the reforms require more of Congress, we must ask whether Congress is well-positioned to meet these new institutional demands. If not, we should think about building additional capacity, perhaps by creating a Congressional Regulation Office.

Whatever regulatory reforms wind up gaining traction in the coming months, there is now a palpable sense of excitement among would-be reformers. With a new administration and likely support in Congress, this may be a moment to reimagine for the better some of the basic ways that American government approaches regulation.

Commentary

Op-edProspects for regulatory reform in the Trump administration

December 20, 2016