Congress created the Paycheck Protection Program with good intentions: help small businesses both to survive and avoid laying off their employees. Giving out over $500 billion certainly helped, but PPP has run its course. Rather than applying for the $130 billion still available, millions of small businesses will close down. Nor, it seems, did the Paycheck Protection Program actually protect most paychecks.

Small businesses and workers still need help, but we need a better way to provide it. Fortunately, there are bipartisan proposals already in Congress to do that.

The Paycheck Protection Program Doesn’t Protect Paychecks

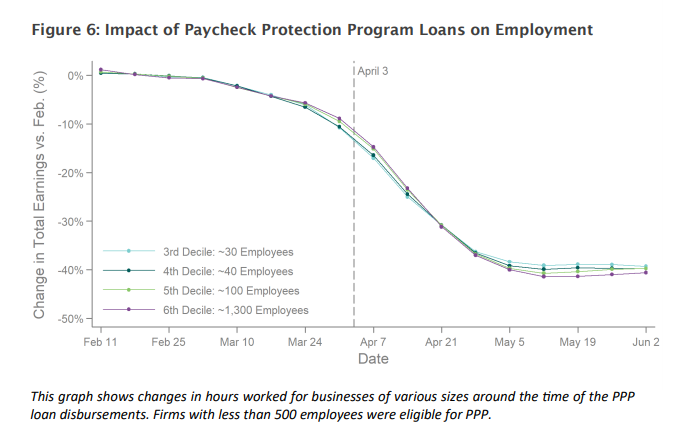

The original hope was that businesses would use PPP loans to pay people who otherwise would be laid off, i.e., “protect their paychecks.” If they did, PPP “loans” became grants that helped both small businesses and the people who worked for them. While some PPP funds were used this way, overall PPP hasn’t preserved many paychecks. A careful study found that PPP-eligible small businesses laid people off just as quickly as other businesses. Other studies came to similar conclusions.

Furthermore, Congress quickly let small businesses off the hook. They lobbied, and Congress agreed, to let them use PPP for other costs instead: to cover rents and mortgages, and to pay only those employees that weren’t furloughed. PPP thereby moved from paycheck protection to owner preservation.

Small Businesses and their Employees Still Need Help

Just because PPP applications have stopped doesn’t mean that small businesses and their workers don’t still need help—they do. Fifty four percent of small businesses told the Census Bureau that returning to normal would take more than six months, or wouldn’t occur at all. Nor is unemployment likely quickly to revert to prior levels: the Congressional Budget Office’s latest forecast projects unemployment of 7.6% at the end of 2021, more than double last year’s level.

But what is needed is not yet another tweak of PPP. As my Brookings colleague Aaron Klein has written, we’ve learned from bitter experience that relying on a loan system operated by banks under the guidance of both the Small Business Administration and the U.S. Treasury leads to favoritism, delay, high costs, and, for many, often no aid at all. Without new approaches, the federal effort will end up favoring large businesses over small and the already-advantaged over racial minorities, the poor, and disadvantaged.

Fortunately, members of Congress are well aware both of the continuing needs and of the shortcomings of the CARES Act they passed four months ago. There have been many proposals from both Republicans and Democrats. In some cases (gasp!) they’re even the same proposals—or at least very similar ones.

Getting Workers Back to Work

The original idea of the PPP—paying businesses to pay their workers until customers come back—makes a lot of sense: businesses stay connected to their employees and can use them as much or as little as they need for whatever customers they have. Their employees keep getting benefits and get paid more quickly and more reliably than from state unemployment agencies. However, many small businesses didn’t use the Program to maintain payrolls because they had more urgent needs, or didn’t trust banks or the government to forgive the loans.

Expand the JOBS Credit Act

Fortunately, Congress in the CARES Act provided an alternative that small businesses prefer: tax credits. The Employee Retention Tax Credit (ERTC) was originally proposed in the Save America’s Main Street Act by Senators Wyden (D-OR) and Cardin (D-MD), ranking Democrats on the Senate Finance and Small Business Committees, respectively. It was included in the CARES Act with bipartisan support. ERTC covers employee costs and is paid automatically by the IRS through the tax system. However, as originally passed, ERTC covered only half of employee costs and only up to $10,000 of wages: companies that didn’t need a worker couldn’t justify paying the rest, so their unemployed employees stayed unpaid.

Now members of Congress in both houses and of both parties are proposing to expand the credit. The Jumpstarting Our Businesses’ Success (JOBS) Credit Act would increase the percentage of total pay to 80%, increase the wage maximum to $45,000, and make the credit available to nonprofits and to more businesses.

The JOBS Act can and should be expanded both to cover more businesses and workers and to incorporate other bipartisan proposals. One important change would be to cover 100% of employee costs for some period of months or until the unemployment rate declines to less catastrophic levels. This would both emphasize and facilitate the return to work, while also taking a burden off the creaky unemployment system. Funding employment directly via the tax system has been shown to be far more effective. It’s being used right now in the UK, Germany, France, Denmark, and elsewhere. Here in the U.S., it’s been proposed in various forms by members ranging from conservative Republican senators (Sen. Josh Hawley, R-MO) to the head of the House Progressive Caucus, Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-WA).

Return to work bonuses and hero pay

Members of Congress of both parties have recognized that returning workers risk COVID infection of themselves and their families. Some have proposed additional hazard pay limited to healthcare and other front-line workers. Others, recognizing that COVID threatens workplaces beyond hospitals and nursing homes, have suggested at least temporary hazard pay for a broader group. This kind of recognition—that workers are taking risks for all of us—could be incorporated into an ERTC and then phased out if and when appropriate. (There would need to be protections to ensure that the increases are not offset by reducing wage rates, which could also be incorporated into the ERTC.)

To bring the unemployed and underemployed back to work while COVID risks remain substantial requires attention to three concerns:

- Higher pay for working than not working

- A return to work “bonus” (i.e., a raise): Higher pay for working now than working before

- Sick pay and health care for anyone who gets COVID-19

These all could be achieved—more reliably and at lower cost—with an expanded Employee Retention Tax Credit.

Grants, not Loans, are Needed to Help Small Businesses Survive

Ensuring the survival of small businesses will, however, require more than just wage subsidies. Businesses whose revenues have been cut substantially by COVID must still pay suppliers, rents, mortgages, and utilities. For many, loans will not work: shops and restaurants that work on slim margins, knowing that a return to normality won’t provide enough to repay the loans, will shut down instead. Larger businesses, by comparison, can weather the COVID storm.

Senators Wyden and Cardin, recognizing this, proposed a grant program, a “Small Business Rebate.” Businesses and nonprofits with under $1 million in revenues and fewer than 50 employees that suffer COVID revenue losses would receive an immediate rebate of 30% of revenues up to $75,000 directly from the IRS via the payroll tax system. Unlike the other COVID programs, there would be no bank applications and no waiting. To ensure that aid is focused on businesses truly in need, Congress could make the rebate taxable next year for businesses that are profitable above some level this year, notwithstanding the reduction in revenues.

Despite vast partisan differences, the COVID pandemic and the depression it’s caused have repeatedly brought Republicans and Democrats into agreements to save the millions who are suffering. It’s past time for them to do so again.

The Brookings Institution is committed to quality, independence, and impact.

We are supported by a diverse array of funders. In line with our values and policies, each Brookings publication represents the sole views of its author(s).

Commentary

Op-edDon’t fix the paycheck protection program, replace it

Congress already has alternatives—and some are bipartisan

July 20, 2020